What’s a floating-rate note and how does it work?

Floating-rate notes are set to be the new thing at the Treasury. Tim Geithner’s crew announced they’ll probably roll out a floating-rate program in about a year. Investors are excited. But most of the rest of us are confused. What’s a floating-rate note? And why do we need one?

Second question, first. Treasury needs a floating rate because it wants to raise more money, and this kind of debt will attract a different kind of investor. Also, some investors are worried about buying too many Treasuries right now because Treasury bonds, notes and bills come with fixed interest rates. And that means they lose value when inflation kicks in, or if interest rates go up. A floating-rate note offsets those problems.

A note is essentially the same thing as a bond, but under a different name. Any Treasury debt that has an “intermediate” maturity of 2 to 10 years gets the name “note.”

So now that’s settled, how does floating-rate debt work?

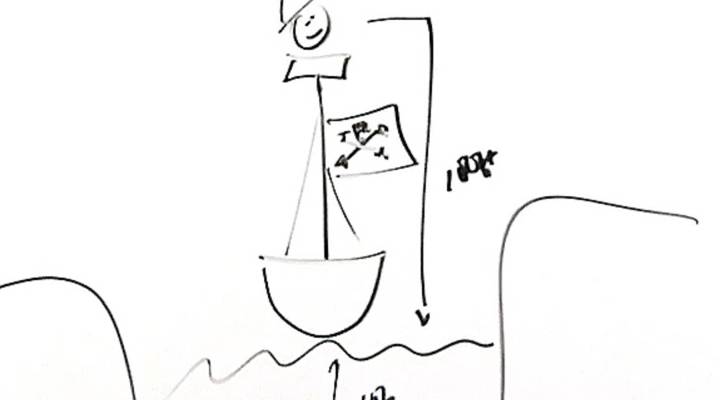

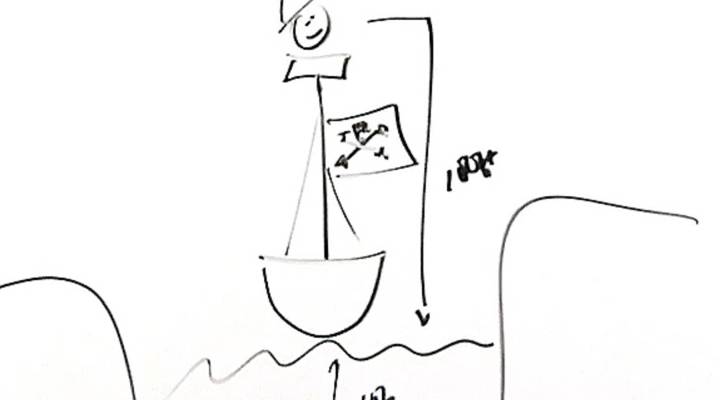

Imagine a peaceful bay in the Caribbean. The tide goes in and out, and in the center of the bay, the distance between the surface of the water and the sandy bottom beneath changes constantly.

Now imagine a pirate ship floating in the bay. The pirate in the crow’s nest, 250 feet up, is a fixed distance from the water. But his elevation above the sea bottom changes with the tide.

He’s floating, in other words — at a fixed distance from the water, but a varying distance above the sea floor.

A floating-rate note works in the same way. The interest rate on the note is like the pirate in his crows nest. It floats a fixed amount above a reference rate, which varies constantly. It goes up and down, just like the distance between the sea bottom and the water’s surface as the tide goes in and out. The reference rate goes up? The interest rate rises a fixed rate above it. The reference rate goes down, and the interest rate lowers accordingly.

The reference rate can be anything that is based on a market rate. Sometimes it’s the prime rate; sometimes it’s the infamous LIBOR; sometimes it’s the federal funds rate.

Floating rate notes are a great investment — if you think interest rates are going to rise. Say you buy the note when it pays 2 percent above LIBOR. If LIBOR is 1 percent, you’re making 3 percent. If LIBOR increases to 2 percent, suddenly you’re making 4 percent. Awesome!

With interest rates at historic lows, interest rates are pretty much bound to rise. Good news for investors. And good news for a Treasury that wants to raise more money. But just like the tide, LIBOR, or any other reference rate can go down as well as up. And leave investors stranded.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.