Shaking up earthquake warning systems

A few seconds of warning before a major earthquake could save lives.

That’s why California legislators passed a bill last year asking officials to set up a seismic early warning system.

The law also requires this system to be a public and private venture, but working out the details of that arrangement hasn’t been easy.

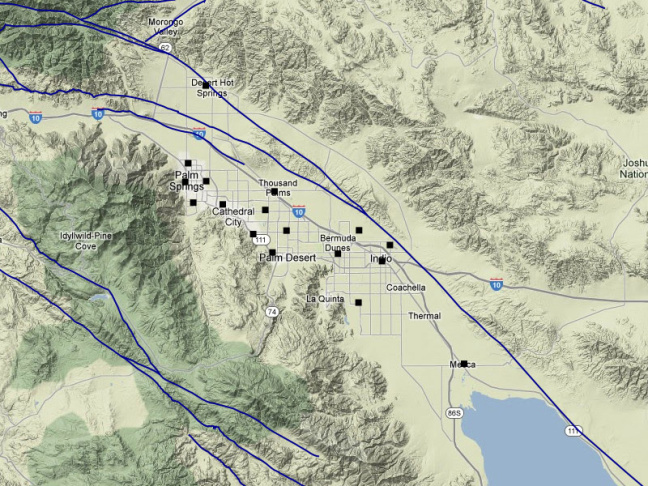

One of the businesses looking to help build an early warning network is Seismic Warning Systems, based in Scotts Valley. The company has already set up sensors in certain locations, including more than a dozen fire stations and a transit company in the Coachella Valley, as marked below.

Blake Goetz at Seismic Warning Systems said the company’s quake alert tool relies on sensors about the size of paperback novels.

“They’re bolted about a foot off the floor in a bearing wall,” he said, showing off the system at a Palm Springs fire station.

Those sensors can detect an earthquake seconds before the serious shaking begins. Goetz says within that brief window of time, the system does three things automatically: “It opens the doors, it turns on the lights and it activates the radio system.”

When that happens, a robotic voice calls out over the loudspeakers, repeating the phrase “seismic event detected.”

This kind of automated response is crucial for fire departments near the San Andreas Fault.

For instance, if the garage doors are closed when the shaking starts, they may get jammed. That happened four years ago to a station in Calexico, Goetz said.

“They had to extricate themselves,” he said. “Meanwhile, there were fires and floods and damage all around their city, and they couldn’t get out of the station.”

In hopes of preventing that from happening again, Imperial County secured a $250,000 grant and hired Seismic Warning Systems to set up a network there as well. Below is an image of where the company plans to install those systems, marked in yellow.

Rocky Saunders, a sales representative for SWS, said the company has cracked the code on quakes.

“We can detect, analyze and warn of a dangerous earthquake in less than one second,” he said.

The sensors work by detecting subtle vibrations called P-waves, which occur just as a quake starts and travel at the speed of sound. They reach the surface before the more damaging S-waves that follow.

It’s that gap of time between the P-waves and S-waves that allow a warning system to do its thing. Saunders said the sensor can even determine the size of the impeding quake.

“We essentially are listening and detecting and analyzing the DNA, if you will, of the earthquake,” he said.

Saunders claimed that the SWS instruments are faster than anything else on the market, including a system designed by the U.S. Geological Survey that works in a similar manner.

While the SWS system currently uses sensors and automated systems in buildings, the USGS network relies on hundreds of sensors around the state installed near major faults. Below is an image of the sensors for that network in Southern California.

But it’s still a prototype. It would require $38 million to build out and $16 million a year to maintain.

Saunders said his company plans to install its own sensors near faults using investor capital. The company will then simply sell early warning subscriptions for about $100 a month.

“So that’s the difference,” Saudners said. “We do not require an investment from the state of California, and then there is a public benefit at a very, very inexpensive cost.”

While the USGS system may cost more, the agency said the system also does more in terms of gathering seismic data and analyzing quake risks. And Seismic Warning Systems still needs to secure more private funding to build its statewide network.

Regardless of the approach, the state wants both systems linked together. But the USGS’ Elizabeth Cochran said that’s easier said than done. “Our concern is that it’s not clear exactly how their system is functioning and whether it’s functioning in the way that they claim it is,” she said.

She pointed out that Seismic Warning Systems won’t divulge the details behind its technology. The company said that information is a trade secret. And while the two sides have met numerous times, they haven’t found a way to get past that.

“It’s kind of a turf war, and that’s kind of bothersome,” said Gary McGavin, a professor of architecture at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, and a former member of the California Seismic Safety Commission.

McGavin thinks the USGS isn’t used to having competition when it comes to statewide early warning, and he thinks the agency isn’t keen on sharing that spotlight.

But, he added, a system relying solely on a private company is risky, too, since private businesses are more susceptible to lawsuits than public agencies.

Either way, he thinks California desperately needs an early warning system and that the two sides should come together to help make that happen.

“And I’m just flabbergasted that there’s so much balking at getting this going,” McGavin said.

According to state law, California has until January 2016 to get a warning system in place.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.