Under the radar: Baltimore’s ‘informal’ economy

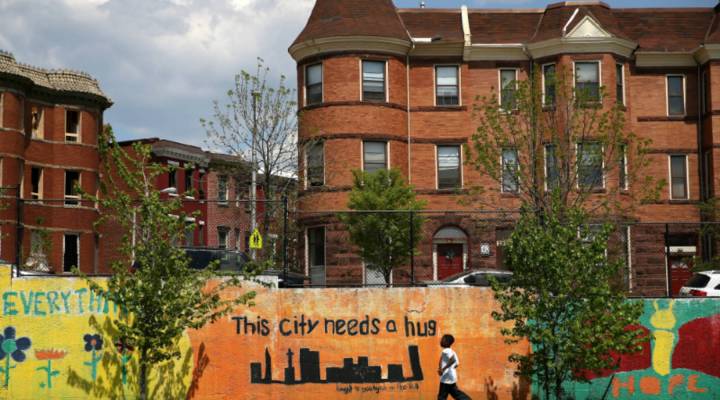

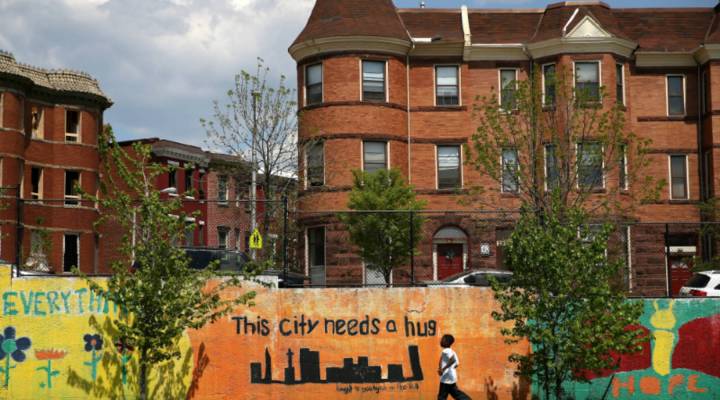

On a warm, early May night in West Baltimore, police cars lined the streets and police helicopters hovered low in the air. To Tina Paul, the noise is like a soundtrack. She rarely notices it anymore. Inside Paul’s house, it was calm. Pictures of her children, her grandchildren and her mother hung on nearly every available surface.

Paul’s mother was a great cook, who made all the family’s food from scratch. But when Paul expressed an interest in cooking, her mom was adamant.

“She said ‘no,’ ” Paul remembers. ” ‘No. The kitchen’s not for you. My girls, you gonna be professionals. You not gonna be in nobody’s kitchen, cooking and cleaning.’ “

Paul heeded her mom’s advice, but Baltimore’s pool of white-collar jobs was shrinking. She was laid off from three businesses in a row, the kinds of companies, she said, that had existed for hundreds of years. After the third layoff, she followed her heart and became a baker. It took every cent she had, but she loved it. Paul says she’d wake from sleep dreaming of recipes. For years, she sold her baked goods informally: at gas stations, on college campuses and at flea markets, where she developed a fan base.

“My biggest customers were the Amish,” she said. “And it just surprised me. I said, ‘You people bake all the time.’ And they said, ‘No, we don’t do this anymore. A lot of our stuff is commercial.’ And they would just buy me out.”

In the mid-’90s, Paul opened Truly Scratch (named for her style of cooking) in Baltimore’s Poppleton neighborhood. She found herself working 20-hour days, catching up on sleep while her car was stopped at red lights. Formalizing the business was challenging and costly. Health Department requirements, like grease traps under the sink, cost thousands of dollars. As a renter, she was always at the mercy of her landlords and at the mercy of what the market in Poppleton could bear.

She shakes her head remembering a piece of advice she received from another baker, who planned to open a shop in a different part of town. He told her he would sell slices of pound cake for $7. And he suggested she do the same. “But the neighborhood could not support a $7 slice of pound cake,” Paul says.

Truly Scratch opened right as federal Empowerment Zone money was flooding into Baltimore. The Clinton administration had chosen six U.S. cities, including Baltimore, to receive a $100 million grant and a host of tax breaks for businesses and employers. Baltimore put the money to work creating jobs. The city’s strategy focused on luring big business and industry to town, and supporting small business owners with low-interest loans and tax credits for hiring. Tina Paul was the kind of small business owner who could have benefited. But no one ever explained that to her.

“This is purely hearsay,” she says. “But from what I understand, the people that got the money were people that already had money. Because from what I understand, you had to spend thousands of dollars to get a lawyer to understand the application.”

Diane Bell-McKoy, who oversaw the Empowerment Zone funds, says Paul’s understanding of how the loans worked is incorrect, but she is certain that many people were similarly mistaken. Bell-McKoy has tried to learn from past mistakes, and today she stresses to anyone who will listen that not all small business owners start with the same base of knowledge. Bell-McKoy is now the CEO of Associated Black Charities. After rioting in West Baltimore damaged hundreds of businesses, she attended a meeting with Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan. There, she heard talk of the Small Business Association coming in to assist.

“I said, ‘please, please be mindful that you can’t just say the SBA is coming in to help,’ ” Bell-McKoy says. ” ‘Do you understand that many businesses won’t know what you’re talking about? They have no idea of this mammoth system of government. They simply will walk away from it.’ “

Residents of former Empowerment Zone neighborhoods say high rates of poverty and unemployment serve to disguise what economic activity does exist.

Louis Wilson is senior pastor of the New Song Community Church in the blighted Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood. He urges visitors to take a closer look before they assume there are no entrepreneurs in Sandtown. “You don’t see any day cares,” Wilson says with a smile. “Oh, there’s day cares. They just aren’t in day cares. There’s car washes everywhere. But they aren’t legitimate car washes.”

For many would-be business owners, the financial challenges of business licenses, rent and insurance prove prohibitive. Working off the books is not.

“We used to have guys that made an actual, middle-class living selling tamales after the clubs closed,” Wilson says. “They park, and they sell tamales and hot dogs and literally made a middle-class living.”

A 2008 study by a nonprofit group called Social Compact found that Baltimore’s informal economy added $872 million a year to the city’s aggregate income. At the time, that represented an estimated 7 percent of the city’s economy.

Alyssa Stewart Lee, president of Sidewalks Group, a consulting firm that researches informal economies, said barriers to businesses like Tina Paul’s are steep.

“There are costs in terms of being able to prepare food for example,” Stewart Lee says. “A food preparer that’s preparing food for the public has to have a commercial kitchen.”

Not if they’re working informally, though. Paul didn’t stop baking. Every summer, she sets up a little stand outside of her house, offering rolls, cinnamon buns and sweet potato pie. She says she opens at 9 a.m. and usually sells out within an hour.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.