Socioeconomic status could be affecting childrens’ brains

When you ask Elizabeth Sowell, a neuroscientist, what she does, she replies, in shorthand: “I do kids’ brains.”

Sowell is a Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Southern California. She conducts her research at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles. Sowell began her research into the link between parental income and child brain development because she was curious about something that scientists have known for years: children who live in poverty tend to have additional problems.

“We’ve known for a long time, from many studies, that children from lower socio-economic backgrounds have more difficulties in school,” Sowell says. “They don’t do as well in cognitive tests. They have lots of problems. We’ve known that for a long time, it’s been documented in scientific literature.”

Sowell wondered what accounts for the gap in things like concentration, vocabulary and memory. She decided to study whether parents’ income made a difference in brain development. She and her colleagues recruited more than a thousand young people from across the country, ages 3 – 20.

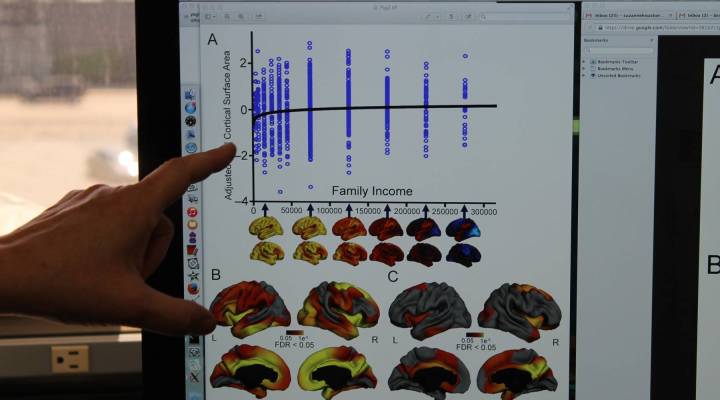

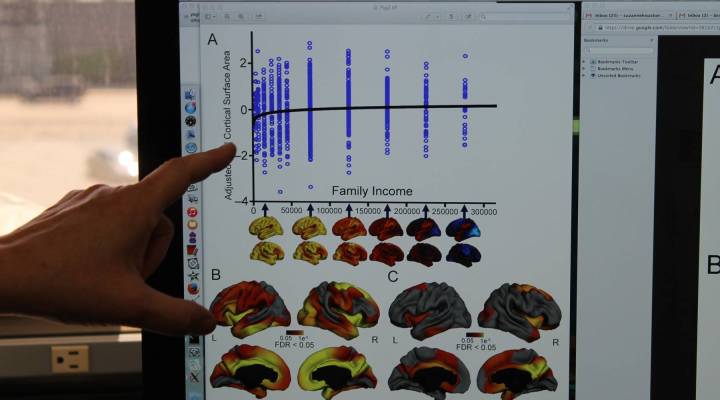

They took scans of the childrens’ brains and asked parents, “How much money do you make?” Sowell says the results were clear.

“If you look at the children whose families made $25,000 a year or less, their brain surface area was about 6 percent smaller than the families who made $150,000 a year or more.”

She’s quick to note that is on average. Some children from upper-income households had brains similar in size to their lower-income peers and vice versa.

Sowell hopes her research hammers home a point about the achievement gap. She says growing up in poverty puts children at a disadvantage, and now there’s evidence that it is a physical disadvantage.

“I think that what this study has done is shown that there’s an actual physical link with the brain,” Sowell says. “It’s really exciting to see it. I want this work to be an impetus to really say, ‘What are we doing with our money?'”

She’s keen to stress the importance of support for things like school nutrition, afterschool programs, and education for low-income parents on the importance of reading to their children. Neuroscientists do know that reading, music lessons and trips to museums physically shape young brains over time.

Sowell’s research couldn’t pinpoint what spending might be responsible for the physiological differences in the brains of low and higher-income children.

She says answering that question will be her next research project.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.