The first corporations — way back — had social purpose

The first corporations — way back — had social purpose

Whom do companies serve? One obvious answer is: their shareholders. But a longer view of the question suggests that has not always been the case.

Today, if you run a publicly traded corporation, shareholder activist Nell Minow of ValueEdge Advisors argues you work for your shareholders. Period.

“At the end of the day, you have to be making those decisions on behalf of the people who have entrusted their money to you,” Minow said. “That’s the entire basis of capitalism. Capitalism isn’t named after the corporate managers, it’s named after the providers of capital.”

It turns out, though, that the earliest corporations did not always direct profits to shareholders. In fact, they didn’t even make profits.

“In the medieval and early modern periods, churches were corporations, towns were corporations,” said Duke University historian Philip Stern, author of “The Company-State.” “So corporations originally served public purposes, not necessarily private ones.”

Dating back to the 13th century, corporations required the approval of governments to serve broader, public interests.

By the 17th century, the definition of “public” included making money and colonizing.

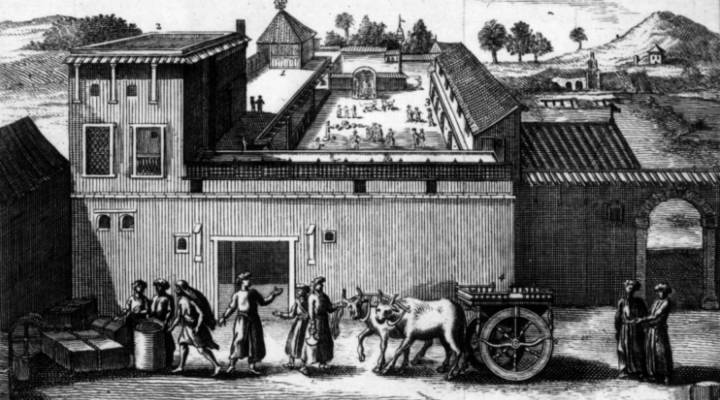

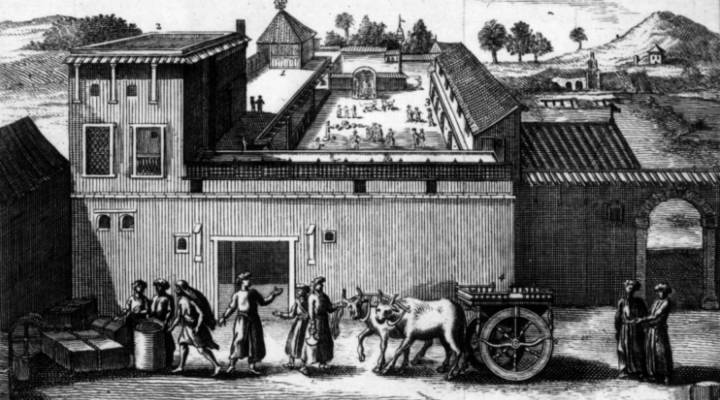

“The colony of Virginia was governed by a company, not by the crown,” Stern said. “Similarly, Massachusetts was governed by a company and not the crown. The British and Dutch ventures in the East Indies were governed by companies. These were institutions that coined money, that made laws, that had courts.”

The East India Company was founded by a group of London businesses and chartered in 1600. Its original mission was to trade for spices, though in the age of British imperialism, the company quickly encountered mission creep.

The company conquered and governed India, shipped slaves from East Africa and traded Indian opium for Chinese tea. And, of course, the East India Company encountered struggles in the tea market in America.

By the mid-19th century, corporations no longer needed state approval and could simply file papers with relevant regulators.

“At this point, the sense of there being some specific public benefit provided was lost,” said University of Denver political scientist David Ciepley, whose forthcoming book focuses on a political theory of corporate order. “And private interests were considered adequate reason to incorporate a corporation.”

This became the dominant model in England and the United States, Ciepley said, because of the legacy of the East India Company. In continental Europe, by contrast, corporate boards balanced the interests of various constituencies, including workers, managers and investors.

“In continental Europe, the notion of who controls is more of a joint affair between these big, inside investors and management,” Ciepley said. “And also — especially in countries like Germany — the workers also have a large seat at the board, at the table. They kind of manage it together in a more cooperative, consensual way, whereas in the Anglo-American countries it is much more a shareholder-dominated board at this point.”

But even in the United States, the pendulum has back and forth in the 20th century. After the Great Depression, many large corporations, including General Electric, General Motors and IBM, emphasized their duties to multiple stakeholders: customers, suppliers, creditors and workers. Often, shareholders were described as a last priority.

But since the 1970s and ’80s, shareholders have leapfrogged back to the top. The point of all this whipsawing is that there’s been continuous debate in history.

“The debates keep coming back to this one central question,” Stern said, “for whom does the company or the corporation work?”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.