When Public Works employed millions

President Trump’s $1 trillion infrastructure plan is still in the nascent stages, but it’s a key part of his promise to create millions of jobs. Once upon a time, infrastructure was this country’s job. Think the Great Depression, public works and the New Deal, when the government employed millions of Americans building airports, bridges, schools, you name it. Between 1933 and 1939, more than two-thirds of federal emergency expenditures went toward public works.

The Public Works Administration alone helped build infrastructure in all but three American counties. Its initial appropriation of $3.3 billion amounted to nearly 6 percent of U.S. gross domestic product in 1933. Other agencies, like the Works Progress Administration, the Civil Works Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, also made building (and repairing) things the nation’s business during that era.

New Deal historian Jason Scott Smith, University of New Mexico, said these were public works programs designed to put people back to work.

“Roosevelt and his advisers saw that building what they called ‘socially useful’ infrastructure would be a central part of how they could drive unemployment down, put the nation back to work and get something tangible and long lasting out of this investment,” he said.

Smith, author of “Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933-1956,” said it’s hard for people today to imagine the depths of economic despair during the Depression.

Up to 2 million Americans “became transients who simply drifted from place to place, wandering across the nation in search of opportunity,” Smith said. The nation’s gross national product had dropped almost a third between 1929 and 1933.

- RELATED: Mega-dams, like Hoover, probably wouldn’t be built today

- Let’s build infrastructure, but we better make it smart

- How one infrastructure project impacts the economy

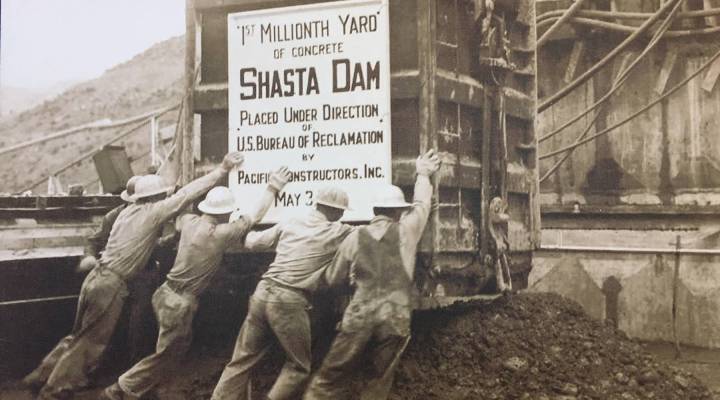

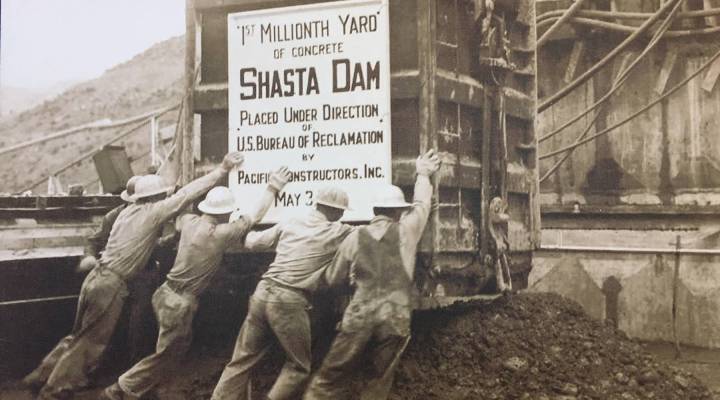

Enter mega-projects like Shasta Dam on California’s Sacramento River, built from 1938 to 1945. It’s a key part of California’s complex plumbing system and helped make the state an agricultural powerhouse.

When California couldn’t afford to fund the project during the Depression, the federal government stepped in. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation oversaw construction. Funding came through the Public Works Administration.

Today, Shasta Dam prevents floods, channels water to cities and farms, and generates hydropower to more than half a million homes.

“It’s integral to the whole economy of California,” said Don Bader, manager for the Northern California Area Office, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Hoover Dam had just been completed and the federal government awarded the Shasta construction bid to a conglomerate called Pacific Constructors Inc. for just under $36 million. That’s about $600 million today. Pacific Constructors and the Reclamation Service, which oversaw construction, started hiring like gangbusters.

On Shasta Dam, “peak workforce was 4,500 folks, 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Bader said. “The overall numbers were about 13,000 to 15,000 different workers over the course of a seven-year period.” Wages for ordinary laborers were a dollar an hour, more or less.

That was much higher than minimum wage, which took effect in the first year of dam construction, at 25 cents an hour. More skilled workers got higher pay, including the men who performed the most risky jobs, like high-scaling steep walls of rock, seen below.

Among those workers was Barbara Cross’s father. Cross, 83, was a little girl when her dad piled the family into an old Chevy truck with all their belongings. They drove to California from Chickasha, Oklahoma, a small college town, because her dad needed a job. They camped along the 1,800 mile route to the construction site. Cross said the first month, she, her two siblings and her parents lived in a tent. Her mother was appalled.

“Most of the women were not impressed,” Cross recalled, laughing at the memory. “It was hard living. They didn’t have running water. It was pretty primitive for them.”

Cross and others like her are known locally as the “dam kids.” Their parents either built the dam or ran businesses in the boomtowns that sprouted up. Despite the “hard living,” most of the dam kids remember the experience fondly. Cross’s husband, Donald, said parents didn’t worry about their children’s safety because “everybody knew everybody.”

Eighty-seven-year-old Del Hiebert’s family moved from Montana, where his dad had owned a grocery store at another federal dam site, Fort Peck. His father ran a store and post office in the boomtown of Central Valley, near the Shasta construction site. Hiebert said the project employed a lot of skilled construction workers, but there were plenty of jobs for the unskilled as well, like excavating rock and hauling brush in triple-digit heat.

“All they wanted was people that were willing to work. And nobody asked, ‘How much do I get an hour?’” Hiebert said. “They just says, ‘I want a job, gimme a job.’”

Shasta and other federal dam projects also produced numerous jobs because they were built in remote places. Crews needed to build or move existing infrastructure in order to build the dam. At Shasta, workers built a conveyor belt almost 10 miles long to transport materials to the construction site. They moved 30 miles of railroad track. Henry Kaiser, the famous industrialist, built the world’s largest cement plant just so he could supply all the cement Shasta Dam required.

An estimated 14 workers died building Shasta Dam. That was a vast improvement over Hoover, where some 100 men died amid workplace conditions that would never pass the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s standards today.

Ruth Ann Kobe’s father worked at both dams. At Hoover Dam, he ran a jack hammer and high-scaled, hanging from ropes high on the canyon walls. Kobe said there were many men willing to do the dangerous work.

“If you got sick and you said, ‘Oh, I can’t go to work today,’ they didn’t come back because the job was taken up,” she said.

Much has changed since the 1930s, of course. Harvard economist Edward Glaeser warns against drawing too many lessons from that era for today.

“I think it’s fundamentally a mistake to think of infrastructure as a job creation program,” Glaeser said.

New Deal public works didn’t fix the Great Depression, he said, but they created a lot of jobs, and, by and large, “good employment.” The New Deal also created infrastructure still in use today.

But today’s employment situation doesn’t begin to compare. And not only because the unemployment rate is much lower today. Glaeser said modern infrastructure builds don’t need as many unskilled workers. We’re not literally moving mountains anymore. And even if we did, we’ve got more technology to do it, the kind that calls for skilled labor.

“Much of infrastructure today is quite technologically intensive,” Glaeser said. “It involves a lot of machines relative to the level of unskilled labor, and thinking that you’re just going to hop readily from one industry to another seems like a mistake.”

Skilled construction workers are in short supply right now.

Richard Walker, director of The Living New Deal, a University of California, Berkeley-based project aimed at documenting the New Deal’s legacy, would still like to see the Trump administration fund a national infrastructure campaign aimed at helping the underemployed that feel left behind by the modern economy.

“Why don’t we insulate every house and apartment in America? Think of the people we could put to work upgrading houses in every city, every town, every rural area to help with energy conservation,” Walker said. “Those are not exotic, sophisticated projects.”

The American Society of Civil Engineers gave the nation’s transit infrastructure a D- in its 2017 report. It’s widely agreed the infrastructure most needed are repairs and upgrades, not glistening new monuments or fundamentally new connections, like the interstate highway system.

“The benefits of connecting America were huge,” Harvard’s Glaeser said. “Today we have relatively good connections as long as we maintain them. And so it’s not that you can’t do anything around the margins, but the benefits are always going to be much smaller.”

Smaller but necessary. Take California’s Oroville Dam. It made national headlines in February when its main spillway started crumbling under historic rains. Fixing the dam won’t take tens of thousands of workers over multiple years, and it won’t solve underemployment. But to the people near the dam who fled their homes in fear of massive flooding, the benefits of the Oroville infrastructure job are priceless.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.