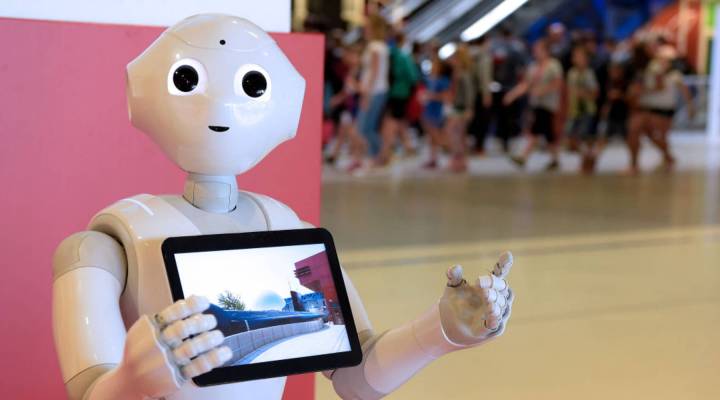

The robots aren’t coming for your job just yet

Robots, we’re often told, are soon going to take all of our jobs and pretty much rule the world. You look at the news and it feels like it could be possible. Just this week, we learned Domino’s is going to partner with Ford to develop driverless pizza delivery cars. Amazon is testing stores with no clerks or checkout lines. However, we’re not being replaced by computers just yet. Marketplace host Kai Ryssdal spoke with James Surowiecki, who wrote about why we don’t need to fear the “Robopocalypse” in Wired. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: Why are you so confident that we need not worry about the Robopocalypse?

James Surowiecki: I think because the overwhelming evidence from what’s happening in the economy suggests that the Robopocalypse, in which robots essentially replace all or let’s say most human jobs, is a very, very long way off. We just do not see any real evidence of it happening right now nor in the short-to-medium term future.

Ryssdal: You look at a couple of things in this piece, the first two are literally the unemployment rate and also worker productivity in this economy.

Surowiecki: Yeah, productivity is the most important one I think to look at, because obviously the premise behind automation and why you would want to hire robots is that they are more productive than humans generally, in other words they can do more in the same amount of time. And if you employ a lot of robots and replace humans, productivity should skyrocket, that’s what you would expect to see. In fact we’ve seen exactly the opposite, productivity has been historically slow over the last 10 or 15 years and it’s been especially slow over the last three or four years when fears of automation and robots have really ratcheted up. And it’s literally the opposite of what you’d expect to see if there was a lot of automation going on knocking human beings out of jobs.

| Say hello to your robot co-worker |

| The most robot-proof job of them all |

| More from our Robot-Proof Jobs series |

Ryssdal: Lots of statistics in this piece. My favorite is this one: of the 271 occupations listed on the 1950s census, only one of them has been rendered obsolete by automation by the year 2010, and that is elevator operator. I love that.

Surowiecki: So that was a great study that was done. And the other obvious one that you would think of would be switchboard operator. There aren’t very many switchboard operators left. My grandmother actually used to do that. But in general, while automation has been a constant force in capitalism really for the last 200 years, automation tends to sort of compliment jobs rather than replace them entirely. So parts of a job will get automated but in general, jobs as a whole don’t necessarily disappear.

Ryssdal: One of the things you have been hearing, in the NAFTA debate that President Trump has started and in the globalization debate that’s been going on in this country for a while, is we’re losing so many more jobs to automation in this country than we are to actual outsourcing. How do you make sense of that?

Surowiecki: Yeah that’s a very familiar and very understandable thing. I mean it’s a logical thing to think, we have all these robots on the assembly lines and therefore that’s the reason the jobs are disappearing. I think the economic evidence at this point suggests that trade and in particular trade with China since 2000 has been responsible for many, many, many more lost American jobs than automation has. Really the jobs lost to trade is just an order of magnitude greater.

Ryssdal: There is a case to be made that automation, when it comes in force, is going to be good for this economy.

Surowiecki: Yeah. So one of the ironies of this whole debate is that we have a lot of sense of concern about the slow economy, the fact that wages are relatively stagnant, and then there’s this question of how are we going to pay for Social Security and Medicare and all these kinds of things. If automation really kicks in, economic growth should rise very sharply. So we will then face the question of how do we distribute the benefits of that economic growth and that’s obviously a complex question. It actually would be probably better if we had more robots and if A.I. actually kicked in more quickly than it looks like it’s going to kick in.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.