Why so much of the U.S. tax code is social policy

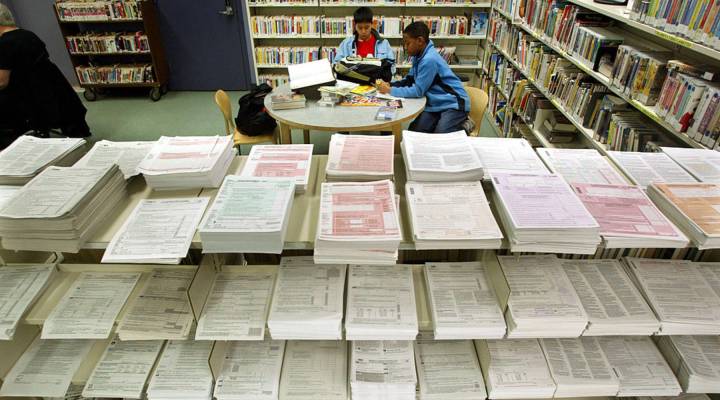

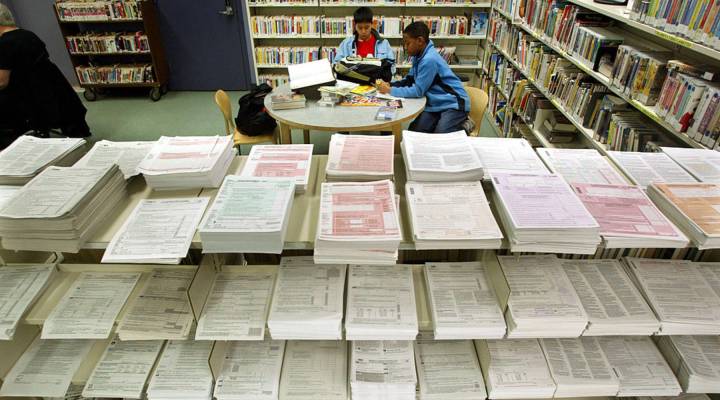

One of the rallying cries for tax overhaul is the need to simplify, simplify, simplify. It should be easier, simplification advocates say, for taxpayers to pay their taxes, calculate their taxes and understand the logic behind the calculation.

But tax simplification isn’t just about clearing up some overwritten, obscure language. And it’s not just about cutting loopholes. Tax simplification, at its heart, requires rethinking some of our shared values and the way our government tries to nudge us to act. Because we ask way more of our tax code than simply raising money for the government.

“We ask our tax code to be an anti-poverty program,” said Daniel Hemel, a law professor at the University of Chicago, “we ask our tax code to be a housing program; we ask our tax code to be a primary way of funding health care in the country.” We ask our tax code to nudge us to be better people: to give more to charity, save more for retirement, spend more on education. “We ask pretty much everything from our tax code,” Hemel said.

No wonder our taxes are complicated. And all the tax credits, tax deductions, tax preferences?

“What they represent is spending,” said Adam Chodorow, a professor at Arizona State University’s law school. “It’s actually disguised spending.”

Spending, because tax breaks cost the government money. Deductions for me or you or Warren Buffet or Amazon, they’re all revenue losers for the federal government.

“In the tax business, we refer to them as tax expenditures,” Chodorow explained. And those tax expenditures add up. There’s currently about $1.5 trillion of federal spending through the tax code.

So why do politicians on both sides push social policy and behavior through taxes instead of just running programs through the budget?

Well, for one, it sounds better.

Imagine if the government wanted to encourage people to buy energy-efficient cars.

“We could send them checks. But that’s spending money,” Chodorow said. Instead, we could promise them a tax credit, and like magic, a spending program has been transformed into a tax cut.

There’s another reason politicians prefer tax code spending over spending through the budget.

“It doesn’t come up every year for review,” explained Joseph Henchman, executive vice president at the Tax Foundation. “Tax credits and tax deductions, once you put them in the tax code, are automatic, unlike spending, which has to get reviewed periodically.”

Out of sight. Out of mind. Once a social program is in the tax code, it’s really hard to get it out. That’s part of the reason meaningful tax simplification is so difficult.

“When you start talking about changing these tax expenditures, changing the provisions of the code, then it becomes public again,” said Dorothy Brown, a law professor at Emory University. If you take away that tax break you sold before, it looks like a tax increase. “Everybody comes out of the woodwork and says this is the worst thing possible,” said Brown.

A meaningful simplification of the tax code, as the GOP is promising, is not about squeezing a filing onto a postcard. It’ll take discussing the tax breaks and the values behind them. And it’ll require a big change to the way both parties do business.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.