Corporate tax cuts: "a heist" or a way to raise wages?

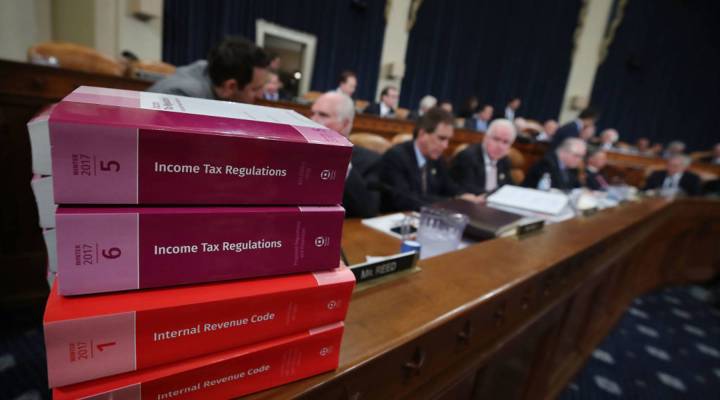

A centerpiece of the planned GOP tax overhaul has been to lower the corporate tax rate, which Republicans have argued will push companies to invest more at home.

Right now, the rate stands at 35 percent, with both the House and Senate calling for a reduced rate of 20 percent. The proposed tax plans would also allow companies to repatriate corporate profits at a one-time lower tax rate. Many corporations have used loopholes to avoid paying the 35 percent rate, such as keeping assets in tax havens abroad.

But questions have arisen over whether companies will actually use tax savings and repatriated profits to invest back here. Will that money just go back to shareholders? And how are we going to pay for the services that these taxes have been paying for?

So to get a better sense of the impact of a lower corporate tax rate, we invited two leading economists with opposing views to talk about the issue.

Economist Jeffrey Sachs: The Republican tax plan is “a heist”

The American taxpayer will ultimately carry the burden of the Republican tax overhaul, according to Jeffrey Sachs, a professor at Columbia University, senior UN adviser and author.

“What will happen is we will have bulging budget deficits, we will have a fiscal crisis, we will have a downturn in the housing market because they are cutting corporate taxes in part by raising the property taxes,” he pointed out.

Even if tax revenues go down, the government still has bills to pay, and that could mean higher personal taxes or cuts in public services, like infrastructure.

“So the Republicans want us to forget the fact that the starting point of all of this is $1.5 trillion of deficits accumulated over the coming decade,” he said.

Sachs said that we instead need to tax the most profitable companies in the world — think Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook — and stop their practice of using offshore accounts in tax havens like Ireland, Bermuda or the Cayman Islands.

“But we’re not talking about anything like that,” he noted. “We’re talking about gifts to David and Charles Koch, to Sheldon Adelson, to Robert Mercer. This is not reform. This is a heist.”

One common counter argument: The current corporate income tax rate is higher in the U.S. than other developed countries (with Europe holding an average tax rate of about 19 percent).

But Sachs argued this won’t put us all on an equal playing field — it’ll just incentivize other countries to lower their tax rates so they can maintain their advantage.

“The big capital owners all over the world are pressing all of their governments: ‘You have to cut the tax rate so that we stay here,’” Sachs said. “That’s the game, and it’s a game in which all the rest of us are losers.”

Economist Douglas Holtz-Eakin: These changes aren’t your parents’ trickle-down economics

Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who ran the Congressional Budget Office during a stretch of the George W. Bush years, said what will be key to successful tax reform is the Republican push for corporate tax cuts in conjunction with a territorial system.

Through this system, companies would be able to bring profits earned abroad back to the U.S., tax free, with a one-time tax on profits already accumulated overseas. What we currently do is tax firms on the basis of their worldwide earnings.

“The way they solve that competitive imbalance is they keep the money and they don’t bring it back and pay that second layer of tax,” Holtz-Eakin said. “That levels the tax playing field. But it has the effect of locking out the earnings of our firms from the U.S. economy.”

Holtz-Eakin said a lower rate (which will give companies an incentive to invest more at home) and expensing (which will allow companies to deduct the full cost of that investment up front) could help with higher wages.

Holtz-Eakins said that in 2016, households headed by people who worked full time saw zero increase in their real incomes, which is the “result of the fact that for the past five years, we’ve essentially had no productivity growth in the U.S. economy.”

While people have criticized trickle-down economics, Holtz-Eakins argued that the term stems from the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which is different from the reform taking place today.

“In 1986, the reform raised taxes on corporations … and it did that so that they could cut tax rates on ordinary income for individuals,” he said. “The notion of trickle down was these marginal rate cuts on the individual side would somehow benefit people lower in the income distribution. We can go back and have a fight about whether that happened or not, but it’s nothing like what’s being contemplated here. I think of this as going directly at the problem.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.