Risk takers still see golden opportunities in California

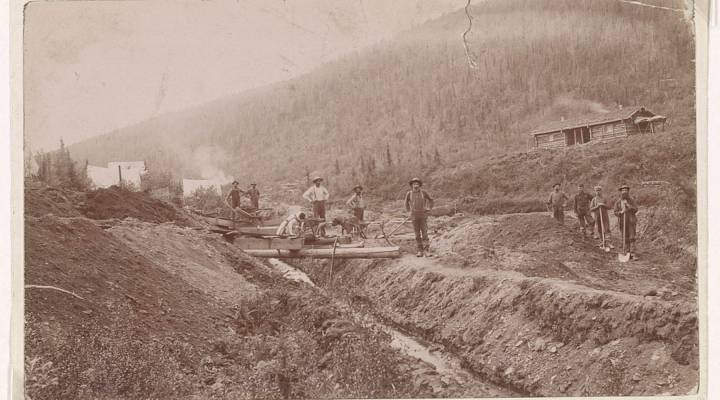

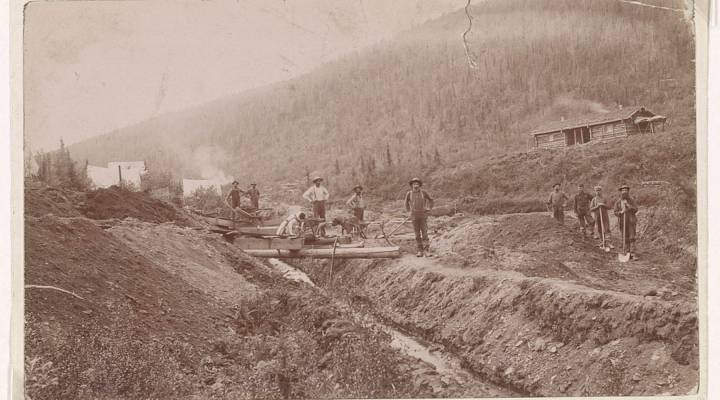

A sawmill worker discovers gold along the American River near Sacramento in 1848. Soon more than 300,000 people rush to California, eager to take big risks in the hopes of getting rich quick.

This founding myth enshrines risk-taking as a key part of the California Dream. Most miners did not find great wealth. But the Gold Rush shaped California’s early economy, putting it on a path to becoming the world’s sixth largest today. And that acceptance of failure continues to attract the kind of entrepreneurs who keep the state’s economy growing.

“The idea that failure could be almost a prerequisite for success — you had to be willing to take those risks — sank roots very early in the California consciousness,” said H.W. Brands, a University of Texas at Austin historian.

Until then, Americans tended to see success and failure as a sign of character, according to Brands. “If one failed in the East, one had to look inside to ask, ‘What’s wrong with me?’”

But those early California miners looked at success and failure differently.

One prospector reached into a stream and pulled up a precious gold nugget. Another reached into the same stream and pulledup a worthless rock. The one who failed to get rich saw the other’s success as little more than luck.

“And I think that attitude toward risk is probably more distinctive in California than just about anywhere else in the United States,” said Brands.

He argues this Gold Rush mentality runs through California’s history. It helped establish an entertainment industry in Hollywood that today contributes $90 billion in annual economic output to Los Angeles County, according to the 2017 Otis Report on the Creative Economy.

An appetite for risk also fueled the growth of Silicon Valley, turning California transplants like Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg, Oracle co-founder Larry Ellison and Elon Musk — CEO of SpaceX and Tesla — into billionaires.

“You’ve got to be willing to crash and burn,” the late Apple CEO Steve Jobs once said in an interview with the Silicon Valley Historical Association. “If you’re afraid of failing, you won’t get very far.”

Indeed, California has seen plenty of high-profile failures. Prominent companies like San Francisco’s Pets.com flamed out quickly when the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s. Silicon Valley lost more than 85,000 high tech jobs in the years that followed.

And for every California success story — think Uber, YouTube or Twitter — there’s a competitor that failed to keep up, like Sidecar, Vidme or App.net.

That graveyard of failure has not deterred a new crop of startup founders from choosing to take their risks in California.

One recently settled into a former rave warehouse in downtown Los Angeles. The blacklight paint and dungeon doors don’t exactly scream “office environment,” but Joe Fernandez said it’s the perfect home for his startup, Joymode.

“It was actually the only place we looked at,” Fernandez said.

Joymode rents fun stuff to people who would rather not own it. The company’s warehouse shelves are stocked with everything from camping gear to movie projectors to giant Jenga blocks.

Joymode, which has about 40 employees, recently raised $14.4 million in a funding round led by South Africa-based tech investment firm Naspers.

Fernandez grew up in Las Vegas and went to college in Miami. But he said he always wanted to get to California.

“I wanted to be an entrepreneur. I wanted to build big things. And it was almost inconceivable to me that you could do that anywhere but California,” he said.

Fernandez originally tried to grow his previous company — the social media influence tracking app Klout — in New York. He said he felt more pressure there to turn a profit fast, to climb to the top and never fall down.

He moved Klout to San Francisco in 2009, primarily to be closer to social media giants Twitter and Facebook. But he said California also just felt like a better place to take a risk.

“In California it was like, anybody could show up, make something crazy, build something important and change the world,” Fernandez. “And if they fail 10 times doing that, that’s OK too.”

In 2014, Lithium Technologies bought Klout for $200 million. Fernandez decided San Francisco wasn’t the right fit for his next company, but he wanted to stay in California. So he launched Joymode in Los Angeles in 2015.

“What we’re doing with Joymode is, we’re trying to challenge the notion of ownership,” Fernandez said. “That’s a really audacious, crazy, likely-to-fail idea. And I think this is the only place you could do that.”

The numbers show that Fernandez’s risk-taking is common here. The Kauffman Index, one long-running measure of American entrepreneurship, puts California first among larger states — ahead of Texas and Florida — when it comes to the percentage of residents starting companies in a given month.

California companies in various industries like software, biotech and entertainment raised nearly $35 billion in venture capital in 2017. That’s by far the largest dollar amount of any state. The Milken Institute’s Kevin Klowden also notes that California leads the country when venture capital investment is broken down as a percent of a state’s overall GDP.

“There are more chances being taken per capita in California in terms of the kinds of investments being done than any other state,” Klowden said.

No state has a higher rate of new companies starting up and older companies failing, according to a recent report from the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF). Bureau of Labor Statistics data from 2014 and 2015 shows that about 22.3 percent of companies in California are either newly starting up or going out of business each year.

That many companies going out of business may not sound great for job creation. But ITIF president Rob Atkinson said this “business churn” is actually good for a state’s economy.

“When you look at all 50 states, the states that were losing businesses actually had a higher rate of job growth,” Atkinson said.

That’s because newer, more innovative companies are stepping in to take their place.

The U.S. Census finds that while companies less than 6 years old only account for 11 percent of overall national employment, they’re responsible for 27 percent of job creation. Meanwhile, companies more than 25 years old account for 62 percent of employment but just 48 percent of new jobs.

Joymode CEO Fernandez said California is not perfect — taxes are high, so is the cost of living. But, he said, “It’s hard to imagine leaving California. Yes, there’s more people. Yes, it’s more competitive. But there’s also more energy, and there’s also more opportunity. And to me that feels well worth the benefits.”

This story originally ran on KPCC.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.