Haitians with TPS help fuel Haiti’s economy, one wire transfer at a time

Haitians with TPS help fuel Haiti’s economy, one wire transfer at a time

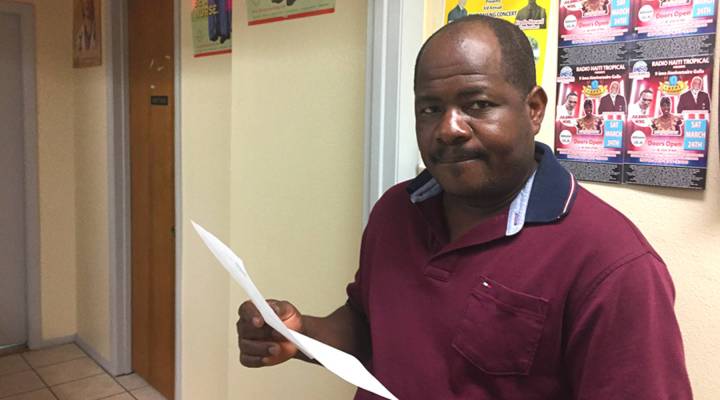

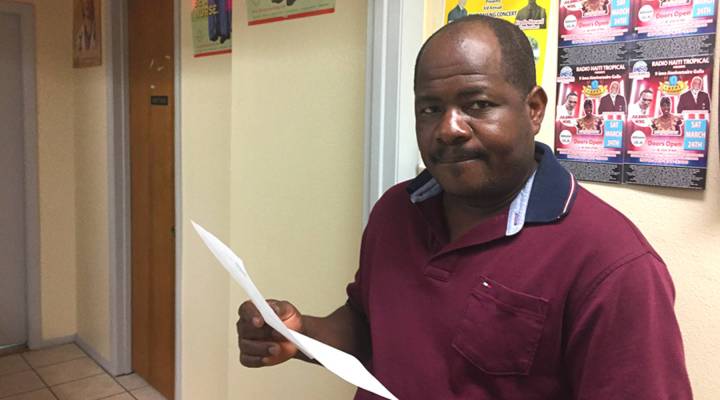

At least once a week, Reynald Justance visits a small, fairly inconspicuous office building on Orlando’s west side. The building, located across from a shopping plaza, is unmarked, except for a yellow sign by its door that reads in French: Authorized CAM Agent Serving the Community.

CAM, short for “Caribbean Air Mail,” is a popular wire service with agencies in Haitian beauty salons, bakeries, shopping plazas — and office buildings.

Justance received a call early one morning from his brother-in-law in Haiti saying he needed money. Within hours, he was walking through the door of the small office building, approaching the counter with a $50 bill in his hand.

“We are making a small transfer, Port-au-Prince,” he told the agent in Haitian creole.

This was Justance’s second day in a row at the CAM agency.

“[My brother-in-law] is very important to me,” he said. “He is my wife’s older brother. He is older than my wife. He doesn’t have a job. That is why I have to support.”

Justance, 47, arrived in Orlando in January 2010 on a U.S. military airlift, just days after the earthquake hit his city and Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince. Within months, Justance had secured a job in the kitchens at Disney World, cooking food some days and cleaning equipment others. He has been able to buy a car and a home, where he lives with his wife, son and daughter.

“I have a lot of family in Haiti,” Justance said. “I have a kid; I have my mother; I have my sister in Haiti; I have friends in Haiti. That is why I send money to Haiti, just to support all these people.”

Justance sends money to family and friends in Haiti at least once a week. He arrived in Orlando on a U.S. military airlift, just days after the earthquake hit the capital, Port-au-Prince, where he lived.

President Donald Trump signed an executive order in 2017 that will end the temporary protected status program that has allowed more than 50,000 Haitians, including Justance, to live and work in the United States. Like Justance, many Haitians received TPS after the earthquake devastated their island. Today, 81 percent of Haitians with TPS are part of the U.S. labor force, according to the Center for Migration Studies of New York. They contribute to their communities stateside, and they also support family members who are still in Haiti by sending back money regularly.

“If we look at remittances from the U.S. to Haiti, they are more of half of all remittances that go to Haiti — so maybe $1.3 billion,” said Stephanie Seguino, professor of economics at the University of Vermont.

That means that if more than 50,000 Haitians have to leave the United States because their temporary protected status is revoked, the consequences could be significant.

“It’s going to create ever more hardship in a country that’s already desperately, desperately poor,” Seguino said.

Data from the World Bank show remittances make up 29 percent of Haiti’s gross domestic product; Haitians in the United States contribute to that.

Much of that money sent to Haiti in the form of remittances is for food, said Norluck Dorange, who offers a wide range of financial services to Haitians in Orlando, including a way to wire cash to the island.

“Someone can call a friend or a family member and say, ‘I have nothing to put in my mouth,’ or ‘My belly’s empty, so do something.’ And these people may come here and jump out of the car and say, ‘I only got $15 to send over there.’ And they send that money,” he said.

With the exchange rate, Dorange said that small amount can go a long way.

“People can go to the open air market and shopping for food for two days for five people.”

The Trump administration said it’s time to end the temporary protected status program for Haitians because conditions on the island are better than they were when the earthquake hit.

Dorange said he thinks a drop in remittance money might force the Haitian government to deal with long-standing issues, such as high unemployment and low agricultural production.

But the country’s weak economy is what forced many Haitians to come the United States in the first place, according to Dr. Idler Bonhomme, president of the Greater Haitian American Chamber of Commerce – Orlando. He said Haitians who now have jobs and pay taxes in the U.S. don’t understand why they may need to leave.

“That’s the hard part for individuals to kind of accept. Why the discontinuation so suddenly when I’m contributing and it’s not a burden?” he asked.

Some members of Congress are calling for Haitians with temporary protected status to receive permanent residency. But for now, the program is scheduled to end in July 2019.

Reynald Justance said he fears what will happen if he has to leave the country. He and his wife have temporary protected status. Their kids are U.S. citizens. He could be split from his family. Again.

“If a final decision is taken to return us to Haiti, it would be like another earthquake,” he said.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.