The disturbing parallels between modern accounting and the business of slavery

The disturbing parallels between modern accounting and the business of slavery

This article was originally published in 2018. It aired again on the June 9, 2020, broadcast of “Marketplace.”

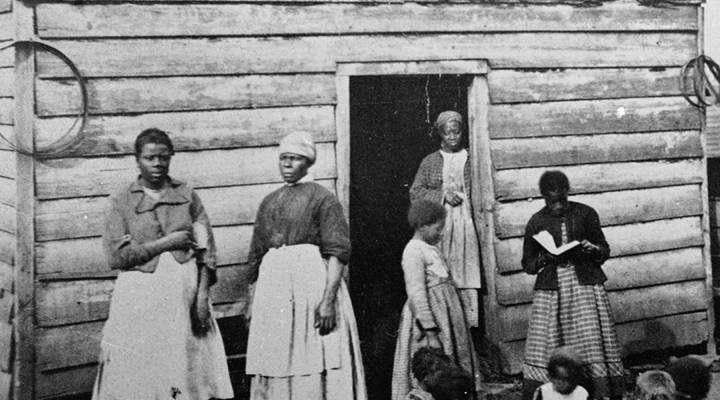

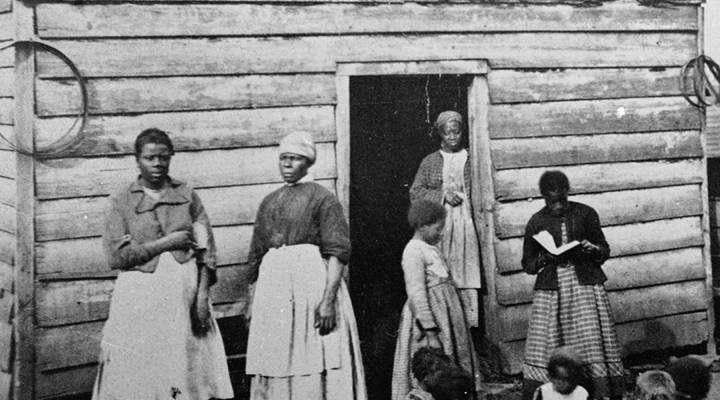

Slavery in the United States was a business. A morally reprehensible — and very profitable business. Much of the research around the business history of slavery focuses on the horrors of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the business interests that fueled it. The common narrative is that today’s modern management techniques were developed in the factories in England and the industrialized North of the United States, not the plantations of the Caribbean and the American South.

According to a new book by historian Caitlin Rosenthal, that narrative is wrong.

Rosenthal is an assistant professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley, and in her new book, “Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management,” she looks at the business side of slavery once it was well-established on plantations. Rosenthal argues that slaveholders in the American South and Caribbean were using advanced management and accounting techniques long before their northern counterparts. Techniques that are still used by businesses today. Below she explains a few examples from the book.

1. Depreciation

Much like a modern business factors in the depreciation of a piece of machinery as it loses value, some “planter-capitalists” applied similar complex formulas to “track the value of slaves as they increase in value, as they get stronger, as they are trained up … but also keeping track of their depreciation as they grow older, if they’re injured,” Rosenthal said, “and these relatively sophisticated valuations even extend to people sometimes receiving a negative value.” Enslaved people knew this, and some slave narratives include references to an illness or an escape attempt lowering their “value.”

2. Productivity Analysis

“Planters, particularly those growing cotton, sometimes measured the productivity of every slave every day,” Rosenthal said. “They paired this data with incentives — both rewards and punishment — to increase output.” Punishments could be severe whipping or other forms of torture. There was even a case where those working in fields might receive a lash of the whip for every pound of cotton they came up short. Rewards might be extra food or clothing. Rosenthal also found records showing that slaveholders ran contests among groups of the enslaved. Often slaves would secretly rebel against such efforts by coordinating to lower overall output.

3. Middle Managers

“Plantation overseers were among the first salaried managers in the country. And, beyond American borders, West Indian plantations often relied on complex hierarchies, including both enslaved headmen and free managers,” Rosenthal said. She re-created the hierarchy of a sugar plantation in Jamaica, which Rosenthal said looks “a whole lot like a multi-divisional American company.”

4. Workforce Planning

Larger plantations, especially those growing sugar and cotton, required an endless stream of human labor in varied jobs. Brutal conditions for the enslaved often meant an early death. Rosenthal said planters carefully tracked the age, health and productivity of various types of workers so they could plan ahead to train children born on the plantation for particular jobs. “Planters trained children in key skills like blacksmithing and carpentry,” she said. “This ensured that they could meet their long- term labor needs. It also raised enslaved people’s market value.”

In an excerpt from her book, Rosenthal explains:

“Beyond the drivers, most categories of skilled labor also included a designated “head.” Scotland was listed as both a field hand and head boiler. He probably operated the sugar house during the appropriate season. Rowland served as head carpenter; Will, head cooper; George, head cattleman; Shadwell, head watchman; Comee, head smith; York, head sawyer; and Hanibal H., head distiller. In some cases, slaves may even have directed the activities of the free white staff. The plantation report for Parnassus lists George Wedberburn, a “doctor’s assistant,” among the white staff. On the inventory of slaves we find two enslaved doctors: Constant, very sickly, and Harry, described as able. Two midwives, Dora and Myrtilla, as well as several nurses are all described as “Old and Weakly.” Wedberburn, the white assistant, may well have aided the enslaved healers, but he probably also surveilled their work and the population in the hot-house.”

5. Lobbying to Protect their Interests

“Slaveholders knew that property was political, especially property in people,” Rosenthal said. Abolition was viewed as unfair government regulation of a thriving private market worth trillions of today’s dollars. Rosenthal said “calculations of the massive size of the total capital invested in human lives were often included in arguments for Southern secession [from the Union]” leading up to the Civil War.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.