Canada’s Aluminum Valley grapples with U.S. tariffs

Canada’s Aluminum Valley is a two-hour drive north of Quebec City, in the region of Saguenay—Lac-Saint-Jean. Five aluminum smelters along a 50-mile stretch of the Saguenay River account for almost half of Canada’s aluminum production.

This has residents here following negotiations between Canada and the United States over a new North American Free Trade Agreement especially closely, with hopes an accord will clear the way to lifting tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum in place since June.

The first smelter opened in this region in 1926 was built by Americans, attracted by plentiful hydroelectricity. The adjoining company town was named Arvida, after industrialist Arthur Vining Davis.

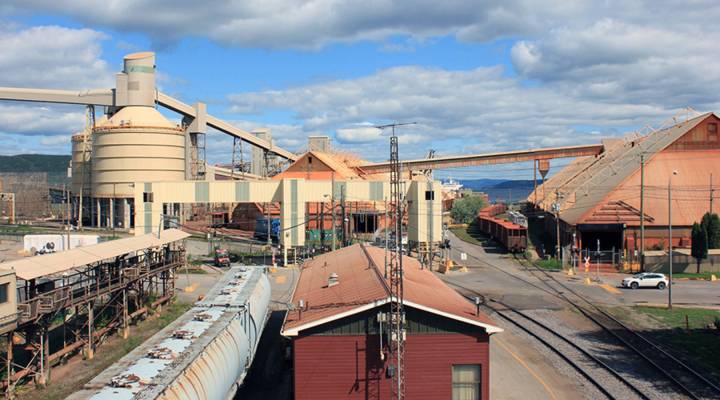

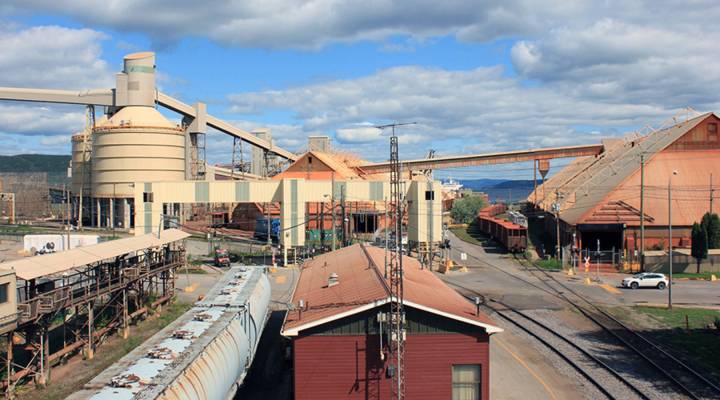

The structures from the Arvida smelter are still part of the large Jonquière Complex, which includes two of the smelters and a refinery.

“My uncles, my father, we had generations of extended family at the Jonquière Complex,” said Alain Gagnon. He started as a machine operator in 1983 and is now president of the National Syndicate of Aluminum Workers of Arvida.

“The situation with President Trump,” he observed, “has recently brought uncertainty to the region.”

After months of threats, the United States imposed a 10 percent import tariff on Canadian aluminum in June. This region’s smelters are now all owned by the multinational Rio Tinto. Last year, they produced 1.2 million tons of primary aluminum, with 80 percent for export to the United States.

Rio Tinto employs 4,000 people in the area, and the tariffs so far have not led to any layoffs. But Gagnon said past experience makes many workers nervous. The big industry here besides aluminum used to be logging, but it was devastated by decades of U.S. protectionist measures.

Gagnon said people stop him everywhere he goes to ask, “Are we about to relive what happened with lumber with aluminum?”

The answer is probably not in the short term, according to Jean Simard, president of the trade group the Aluminum Association of Canada. He said U.S. manufacturers depend on imported aluminum. Canada is their No. 1 supplier.

“They’ve developed a world-class downstream industry with 160,000 jobs,” he observed, “processing it to make cars, planes, building and construction components.”

Right now, Rio Tinto said customers in the United States are paying the cost of the tariffs. But the cluster of smaller businesses in the Saguenay area doing further work on the aluminum before it’s exported don’t have the leverage to ask buyers to take on what amounts to a price hike for their product.

Last year, the region’s smelters produced 1.2 million tons of primary aluminum, with 80 percent for export to the U.S. Rio Tinto transports raw material and finished ingots to and from its five smelters in the Saguenay—Lac-Saint-Jean region by train.

“We buy full raw ingots, full-sized slabs from Rio Tinto,” explained Simon Holsgrove, head of sales for PCP Aluminum. “As we move down the line, they get cut into plates and moved into a milling process,” turning the aluminum into forms needed by manufacturers.

One of the largest machines on the factory floor flies a small Quebec flag. However, this sort of processing is also done in the United States, according to PCP’s President Michel Lavoie.

“We have many competitors in the U.S.” Lavoie said. “That’s why I can’t push 10 percent more to my customer and think that we will be competitive with that.”

Most of PCP’s clients are in the United States, and the company has had to pay the tariffs itself to continue selling to them. Lavoie’s looking for ways to make up some of that 10 percent in savings on his operations, though not with layoffs.

His biggest hope — like for many in this region — is that Canada negotiates an end to the aluminum duties.

Marlène Deveaux, president of the Aluminum Valley Society and head of her family-owned business, still worries there could be lasting damage.

“Before, it was something so natural to work with the U.S. back and forth, but even the quality of our relationship, the way that they’re talking to us, it’s changed,” she said.

One U.S. buyer recently told Deveaux that even though she has a cheaper product, the customer was still switching to a U.S. supplier out of national pride. The tariffs may go away, but she fears some of the bad feelings arising from the tariffs may not.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.