A long quest in Texas for a better voting machine

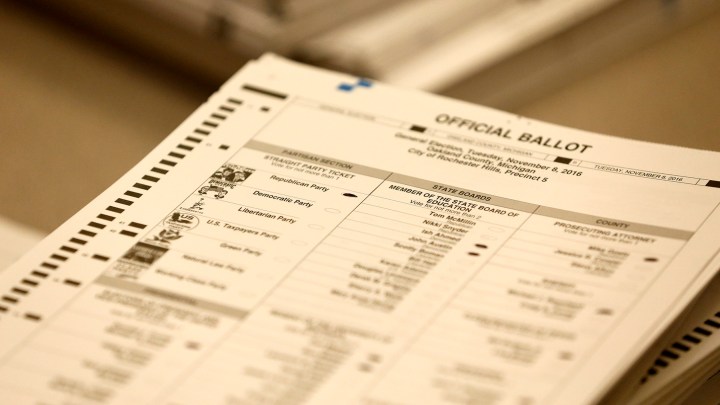

Marketplace Tech is talking election security and technology as midterms approach. One of key conversation is about the oldest voting tech of all: paper.

Remember the 2000 presidential election fiasco over the hanging chads, those tiny bits of paper that stuck to paper ballots? They confused vote counters so much the Supreme Court eventually had to decide the election.

In 2002, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act. It set new voting standards and gave election offices a bunch of money, mostly for new electronic voting machines. But within a few years, election security officials were asking for a good old-fashioned paper trail.

Dana DeBeauvoir runs elections in Travis County, Texas, which includes the city of Austin. She said several of the vendors made slapdash efforts around 2006 at creating paper trails for their electronic voting machines.

“It was a rather gigantic failure,” DeBeauvoir said. “If you can imagine a voting system with a cash register tape under glass, this was how most of the voting audit trails were developed. So very quickly this paper trail fell by the wayside. And for many years what came after was the reminder that this failed once. Vendors were not going to try it again.”

So DeBeauvoir set out to design her own voting machine. It was called STAR-Vote. It’s an acronym for secure, transparent, auditable and reliable.

“With STAR-Vote, what we said was ‘Let’s try to fix several of the problems that we have with electronic voting, including the fact that it’s too expensive,'” DeBeauvoir said. “So we wanted it to be an open-source system. We wanted it to be very easy for voters to use. So it had to be something that they could take the paper out of the machine and look at and examine themselves.”

The system would let both voters and election officials verify that votes were cast correctly. After some heavy lifting on a design, DeBeauvoir went looking for someone to build her dream voting machine. There were no takers. Last year, she went back to the voting machine vendors to see if they could meet two of her requirements.

“One of them is we must have a paper trail that actually works,” DeBeauvoir said. “And we must have the capability to use that paper trail. We have to be able to conduct post-election audits.”

And, it turns out, one company was able to make that work.

“That’s good news,” DeBeauvoir said. “The marketplace has come a long way, even if it has taken us 15 years and the incredible patience of voters to get this far.”

Unfortunately, the new machines aren’t expected to roll out until 2020. But paper receipts are finally part of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s guidelines for voting machines. And DeBeauvoir said that’s the key to making sure voters feel confident about voting.

“I don’t think it’s a matter of just trust,” DeBeauvoir said. “I think it is actual proof of the veracity of the election. Once we have a paper trail, then I think it’s very difficult to call any election into question.”

And now for a few tech stories that have caught our eye:

From the Financial Times, a story about a study out of Oxford University that’ll make you never want to install an app again. It looked at more than 950,000 apps on the Google Play Store in the United States and the United Kingdom and found that almost 90 percent of them are set up to send information back to Google.

Forty-two percent can send information to Facebook, others to Twitter, Verizon, Microsoft or even Amazon. And, of course, some ad networks and data brokers. This can include your age, gender and location, plus information about what other apps you have installed. Google said the researchers were confusing basic crash reports and usage analytics with data sharing. Google said app developers have clear guidelines for how they can use those analytics. But the researchers said it’s clear that app developers are ignoring those guidelines. News apps, games and children’s apps seemed to send information to most third parties.

And speaking of the children, in case you missed it, an astonishing story out of Florida Monday. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration said it told a shuttle company to stop testing a self-driving school bus with actual children in it. The company, Transdev, had gotten permission to test an autonomous shuttle, but NHTSA said not as a school bus.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.