What federal funding for civics reveals about American political discourse

What federal funding for civics reveals about American political discourse

The impeachment inquiry into President Donald Trump is generating debate about checks and balances, presidential versus congressional power and just what requirements the Constitution lays out for impeachment.

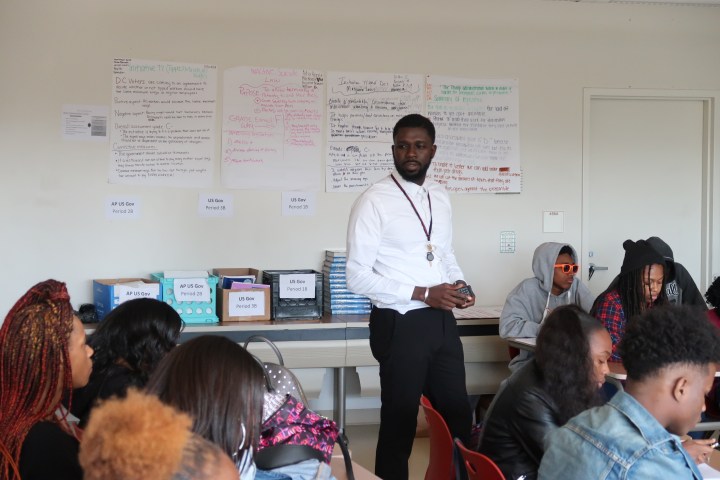

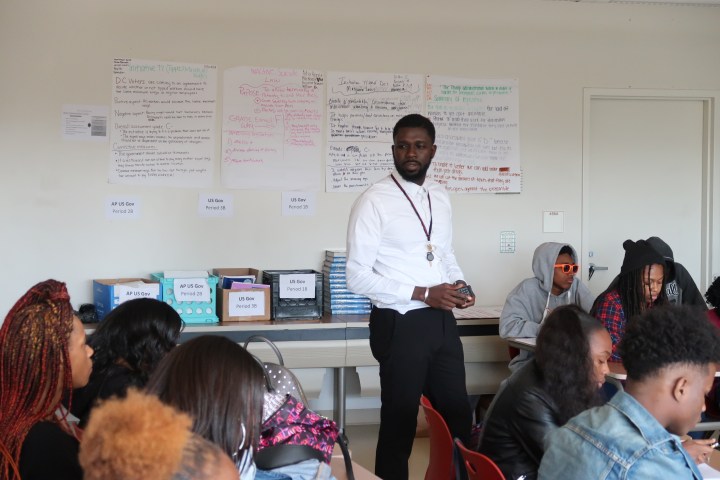

That means it’s a hot topic for discussion in the classroom of Oumar Diallo, who wrangles a 12th grade American government class at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C.

“We do our absolute best to mingle contemporary events into the curriculum, just so it’s more relatable to the kids,” Diallo said. For the impeachment discussion, he said, “We used the [President Bill] Clinton case as a case study. And the goal of the activity was to have the kiddos indicate where in the Constitution one can refer to in order to find out what it would take for a president to be impeached. And they found out how loose the language was.”

These are tough questions for even constitutional scholars, let alone high schoolers. According to the Annenberg Civics Knowledge Survey, only about 40% of Americans can name all three branches of government, and about 20% can’t name even one. The group does find the vast majority of Americans know Congress can impeach the president. But many education experts worry a recent lack of focus on civics education has people at a disadvantage for the details.

“Very few people in the United States understand the [political] system,” said Charles Quigley, executive director of the Center for Civic Education. “And that’s a major problem with people consuming what’s going on now, with the move to impeach the president and so forth, that people don’t even know how impeachment works.”

Quigley’s group is one of the few that still receives some federal funding to provide civics training to teachers and students, in addition to free resources for classrooms. It just received two competitive grants from the Department of Education.

The vast majority of money for school programs comes from state and local governments, but the federal story reveals a trend, according to Ted McConnell, executive director of the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools.

As recently as the early 2000s, McConnell calculates the federal government spent around $40 million a year on civics programs. But 2010 was a turning point. Congress changed how some education programs were funded, shifting more dollars toward STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education, leaving subjects like civics scrambling for what was left over. Now the federal government spends just $4 million a year on civics, compared to almost $3 billion a year on STEM.

That’s $54 per school child in this country [for STEM] as opposed to the very paltry amount of about five cents per student spent on civics.

Ted McConnell, executive director of the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools

“That’s $54 per schoolchild in this country [for STEM] as opposed to the very paltry amount of about five cents per student spent on civics,” McConnell said.

This has classrooms relying on free resources provided by the many nonprofits and other groups working in civics education, most of whom receive their funding from foundations and grants, such as the Center for Civic Education. Many teachers still use “Schoolhouse Rock” as a teaching aid.

Civics has always received a lower share of federal dollars than many other subjects, and states and local school districts are in a rough spot when it comes to finding resources and time to squeeze in civics when standardized testing and the job market demand other skills.

“As a country, we don’t train students in STEM as well as other high-performing countries. There’s no question we need to do better by our students in terms of preparing them for the economy they’re going to graduate into and preparing them for the jobs of tomorrow” said Catherine Brown, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. She was part of a team that took a state-by-state look at civics education in 2018. “I wouldn’t argue that we should cut back on STEM. But there’s also no question that we need to teach students to be informed citizens, and it’s part of what it means to be an American.”

The quality of civics training for students can vary greatly by school district and by state. But according to a 2018 survey of school principals by the Education Week Research Center, most school leaders said they were spending “too little” time on civics and said “that their top civics-related challenge is the pressure to focus on other subjects because they are tested or emphasized.”

Several states, including Illinois this year and Massachusetts last year, are revising laws to put more emphasis on civics education. A bill introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in January would channel another $30 million toward teaching kids about how the American government works, including practical applications of that knowledge.

The practical aspects of civics knowledge is the focus for teacher Oumar Diallo in Washington, D.C.

“My goal in this class is not for the kiddos to cite and recite the United States Constitution, but to at least know … where to go to refer to your rights and whatnot,” he said.

Diallo said all the talk of impeachment will inform an upcoming lesson on the executive branch and just how checks and balances work in practice.

Reporting assistance provided by Christian Buckler.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.