What if Florida caused the Great Depression?

The following is an excerpt from Christopher Knowlton’s new book, “Bubble in the Sun: The Florida Boom of the 1920s and how it brought on the Great Depression.”

At high tide on the clear morning of January 10, 1926, to the squalling of circling gulls, the Prinz Valdemar, a five-masted steel-hulled barkentine, weighed anchor. With the help of two tugboats, she prepared to navigate the narrow channel known as Government Cut that led into the turning basin of Miami Harbor. Her captain and crew of eighty were understandably impatient: they had waited ten days for their turn to be towed into the crowded harbor. Many of the crew stood at ease at her deck railings and watched the tugs at work. As they knew well, the Prinz Valdemar was a dinosaur of the great age of sailing ships and, at 241 feet long, likely the largest vessel ever to enter the harbor. Built in Denmark in 1891, she had weathered many transatlantic crossings and countless storms at sea until the outbreak of World War I, when the German navy deployed her as a blockade runner. In a later incarnation, she had hauled sacks of coconuts up from Nicaragua. The plan now was to convert her into a floating hundred-room hotel to help meet the acute housing shortage in Miami, which, like the rest of Florida, was in the midst of an epic building boom.

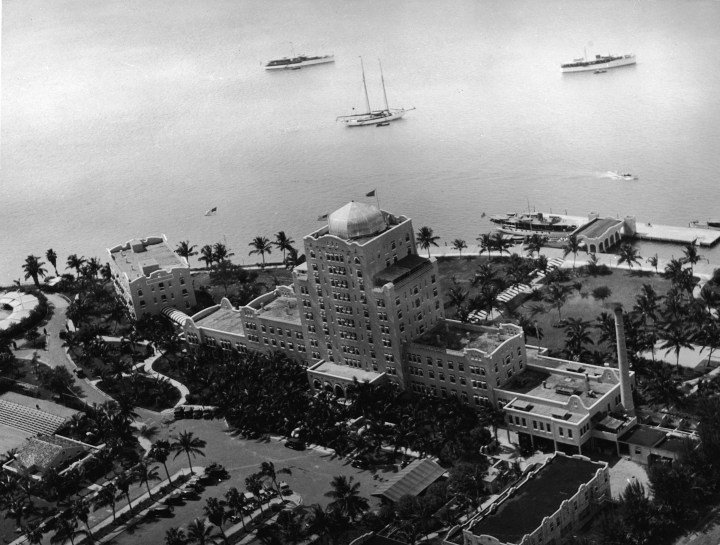

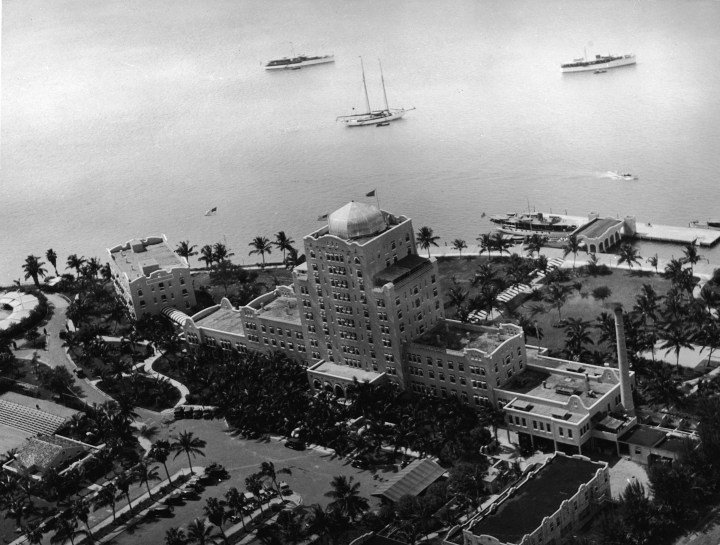

Thirty-six other ships, mostly steamships and schooners, already jammed the inner harbor, vying for berths and wharf space to unload their cargos of building supplies. The steamers were tied up three deep at the city piers. An additional thirty-one ships lay at anchor outside the harbor, awaiting their turn to enter, loaded with enormous amounts of lumber — millions of feet, by one estimate — to say nothing of the wallboard, plumbing fixtures, and roofing materials destined for various construction projects up and down the coast.

Precluded from entering the port, passenger ships arriving from Havana, New York, and as far away as San Francisco had resorted to anchoring off the coast and ferrying their passengers ashore on launches and tenders. At night, with their rigging lit, the forest of masts and rows of bright port- holes suggested an ethereal, glittering city bobbing on the horizon.

But nothing seemed more fantastical than what was actually happening onshore. From the deck of the Valdemar, the crew could see the skeletons of a dozen new steel and concrete skyscrapers sheathed in scaffolding and jutting into the sky, creating a new urban skyline where only one multistory structure had existed just eighteen months before. Three tall hotels along the bay-front area of downtown Miami—the Columbus, the Watson, and the Everglades — were framed in steel girders but remained unfinished. Behind them rose the Meyer-Kiser Bank Building on Flagler Street, also still under construction, and the three-towered McAllister Hotel. Tallest of them all was the recently completed Miami Daily News Building a few blocks north. The year before, the newspaper had set a world record when it published a 504-page edition in twenty sections, loaded with real estate ads and weighing 7.5 pounds — requiring fifty rail cars full of newsprint to produce. To celebrate its unprecedented success, the paper had built this twenty-six-story skyscraper and crowned it with an elaborate tiered bell tower modeled on the Giralda tower that sits atop Seville Cathedral in southern Spain.

Pandemonium raged on Miami’s city streets — and on the streets of all the new cities and towns that had sprung up along both coasts of Florida during that decade. “My first impression, as I wandered out into the blazing sunlight of that bedlam that was Miami, was of utter confusion,” remembered Theyre Hamilton Weigall, a twenty-four-year-old Australian- born, London-based journalist who arrived in Florida by train at the peak of the boom and stood stunned among the screeching motor horns and the deafening cacophony of rivet guns, drills, and hammers. “Hatless, coatless men rushed about the blazing streets, their arms full of papers, perspiration pouring from their foreheads,” he recalled. “Every shop seemed to be combined with a real estate office; at every doorway, crowds of young men were shouting and speech-making, thrusting forward papers and pro- claiming to heaven the unsurpassed chances they were offering to make a fortune. . . . Everybody in Miami was real estate mad.”

Land sales caused small riots where crowds literally threw checks at the developers—in such numbers that they had to be collected in barrels.

Building projects in the Greater Miami region totaled $103 million in 1925 ($1.5 billion in today’s money), a huge figure for the day. But an embargo imposed by the Florida railroads in September 1925 had compounded the chaos and overcrowding in the harbor and on the city’s streets. Lacking the requisite warehousing, logistics, and labor, the railroads had been overwhelmed by the avalanche of building materials pouring into the state. Until order could be restored, the tracks repaired, and new warehouses built, all cargo into Florida was now banned, except fuel and perishables. A milk bottle shortage emerged; ice had to be rationed; local cows, deprived of feed, began to starve. By year-end 1925, thousands of railroad cars were backed up in Jacksonville and other gateways to the state.

One enterprising businessman tried to smuggle in a rail car full of building bricks under a layer of ice, in the guise of a shipment of lettuce. Others tried to move their supplies in by steamship and schooner, and when that didn’t work, by truck, clogging the highways in and out of the state — highways still rough and already jammed with automobiles, all bound for the new promised land of Florida, dubbed the last American frontier. Adding to the chaos at the piers and railroad stations were the endless stacks of crates, the beginnings of what would be a record citrus crop bound for northern markets — but at the moment, going nowhere. The Miami dockworkers seized on the demand for their services to strike for better wages — 60 cents per hour, up from 45 cents. Soon thereafter 1,800 telegraphers went on strike, too, hampering communications.

Nowhere was the speculation as feverish as it was along the waterfront of Dade County, where prices for bare plots of land were doubling and tripling, seemingly overnight, including those that had yet to be dredged from the bays. As property values exploded, the speculation extended to the selling and reselling, numerous times in a day, of paper options on these parcels. Land sales caused small riots where crowds literally threw checks at the developers — in such numbers that they had to be collected in barrels. Seminole Beach was bought for $3 million one day, then sold three days later for $7.6 million. One Miami real estate office sold $34 million worth of real estate in a single morning.

But the construction boom in Florida was by no means limited to the coasts. Countless inland communities were under development as well. In addition to the celebrated subdivisions of Miami Beach, Coral Gables, Boca Raton, and Davis Islands were literally hundreds of others — by one estimate, 970 — of varying sizes around the state with names that evoked garden-like settings or tropical Spanish paradises, such as Jungle Terrace, Altos del Mar, Opa-Locka, and Rio Vista Isles.

Many of these developments were being built around golf courses that were a major selling point in every resort’s lavish brochure. In fact, the state was on its way to boasting the world’s largest concentration of golf courses, a distinction it holds to this day. In all likelihood, some twenty million lots were for sale across Florida. As Willard A. Barrett, a writer for the financial publication Barron’s, noted, to occupy them all would require a Florida population of sixty million — or roughly half the existing population of the United States at that time. Problematically, Florida, by the late 1920s, had only one and a half million residents, although that was up 50 percent from the start of the decade. Nevertheless, that didn’t discourage outsiders from spending more than $1 million per day to buy up Florida property in 1925. By then, the Florida land boom had evolved into a historic investment frenzy. Barron G. Collier, who had purchased more than a million acres in southwestern Florida — a parcel larger than the state of Rhode Island — very likely became the nation’s first billionaire, at least on paper, when the value of his Florida holdings spiked during this period. “Something is taking place in Florida to which the history of developments, booms, inrushes, speculation, and investment yields no parallel,” reported the New York Times in March 1925.

As the Prinz Valdemar entered Government Cut, the Clyde Line ship George Washington, loaded with one hundred impatient passengers bound for New York, began to sound its ship’s whistle, announcing its intention

to depart the harbor the moment the Prinz Valdemar had cleared the channel. At that moment, an accident occurred that seemed foreordained. Someone ignored a command, or missed a signal, or a gust of wind blew in from offshore, or the tide shifted — no one could be entirely sure which of these factors was most responsible for the mishap that followed.

The huge gray-hulled sailing ship bumped up against a sandbar, swung sideways, and wedged itself across the mouth of the eighteen-foot-deep channel. As the tide began to recede, the weight of the outgoing seawater swung the giant keel out from under the vessel so that her cargo of supplies shifted. The old ship, her iron sides grinding, groaning, and creaking, cap- sized in a slow-motion pantomime that took an agonizing four minutes to play out, allowing her crew ample time to leap overboard into the luke- warm, blue-green waters of Biscayne Bay. As her five masts gradually genu- flected, water rushed over her gunwales until she came to rest on her side, half submerged, so that she stoppered the channel like a cork in a bottle, preventing all but the smallest boats from passing in and out of the harbor. Frantic efforts were made to right the great ship. Thick ropes called hawsers were cleated to her decks and hauled by the tugboats to try to pull her upright. When these efforts failed, a pair of dredging vessels were assigned to carve out an eighty-foot-wide temporary channel that could bypass around her. Both dredgers struck coral and broke down. A second vessel, the steamer Lakevort, tried to squeeze past the wreck only to run aground herself, further complicating the salvage operation.

Meanwhile, on board the George Washington, now trapped in the harbor, hysteria mounted. The governor’s office in Tallahassee was flooded with telephone calls and telegraphs demanding that Governor John Martin fire the harbormaster. Overnight all the frantic building construction up and down the East Coast was forced into a near-complete standstill. By now, the state’s entire transportation system — its rails, its roads, and its seaports; the infrastructure that built and sustained the great boom — was either clogged, stalled, or broken.

This forced recess gave developers a chance to review their projects. One by one, in offices across the state, they pulled out their drawings and their blueprints, their contracts and their budgets, and spread them out on their drafting tables to reconsider every nuance of their ambitious plans. A few of them, after doing so, decided that the prudent course of action was to pull back a little. In Wall Street parlance, they opted to take some of the risk off the table; but they would be the exceptions.

The land boom, not the stock market, was the true catalyst for the disasters that befell the nation as overvalued housing and property prices everywhere began to collapse in the wake of the Florida debacle

The 1920s are best remembered as the era of the flapper, jazz, the automobile, radio, Prohibition, and rum-running. But in isolation, perhaps nothing reflects better the spirit of this rollicking decade than the remarkable sequence of events that transpired in Florida. Impressive skyscrapers had been built before, and a few suburbs had been drawn up in places such as Shaker Heights, Ohio, but not on the colossal scale of what occurred in Florida during the twenties. Up and down both coasts, entire cities were mapped out, or platted, from scratch, with much of the land somehow dredged up out of swampland or sand, and sold, seemingly overnight, to the property-famished public.

The great Florida land boom would prompt the country’s greatest migration of people, dwarfing every previous westward exodus, as laid-off factory workers, failing farmers, disaffected office clerks — anyone unemployed or seeking a better quality of life — boarded southbound trains or climbed into their Tin Lizzies and made their way to this emerging land of opportunity, touted as a tropical paradise. Six million people flowed into the state in three years. In 1925 alone, an estimated two and a half million people arrived looking for jobs and careers, and, for a time, found them in the building trades. As one observer wrote: “All of America’s gold rushes, all her oil booms, and all her free-land stampedes dwindled by comparison with the torrent of migration pouring into Florida.”

Florida, which began the decade as America’s last frontier, would end the decade as the country’s most celebrated playground — and its favorite retirement destination. Furthermore, it quickly became the bellwether for every important social and economic development of the period, and has remained a bellwether ever since.

And yet historians and economists have largely overlooked the boom’s larger significance, specifically its direct impact on the severity and duration of the Great Depression that followed. Most cite the stock market crash of 1929 as the event that heralded the Depression. In fact, the bursting of the great Florida land bubble was the more pivotal event—the one that truly, if tragically, triggered the nationwide economic and social trauma that followed, and the one that helps explain why it lasted so long and was so devastating. The land boom, not the stock market, was the true catalyst for the disasters that befell the nation as overvalued housing and property prices everywhere began to collapse in the wake of the Florida debacle. The eroding economic fundamentals and collapsing consumer confidence finally reached Wall Street and pulled down the stock market, bringing an end to the frantic nationwide party so aptly named the Roaring Twenties. In short, the great Florida land boom was one of the most consequential financial manias in US history, and yet to this day, it has never received the attention it deserves. One reason for this has been the paucity of economic data to fully explain the event — in particular, limited government statistics from the era relating to home prices, household wealth, and foreclosures. Another reason is that the significance of the boom has not been understood in a broad enough historical and business context. One goal of this book is to remedy those omissions and oversights. Another goal is to tell the story through the experiences of the characters who led the boom and were most responsible for its magnitude and repercussions.

From “Bubble in The Sun” by Christopher Knowlton. Copyright © 2020 by Christopher Knowlton. Excerpted with permission by Simon & Schuster, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.