As home prices rise in big cities, holding out hope of buying

Just down the street from the Blackstone Community Center in the South End of Boston, there’s a two bedroom condo for sale for $1.2 million. That’s pretty typical for the neighborhood, which is one of the wealthiest in the city.

Even in more affordable neighborhoods, prices are out of reach for most people. The median single family home price in the Boston area is now over $600,000, and the median condo price is not much lower.

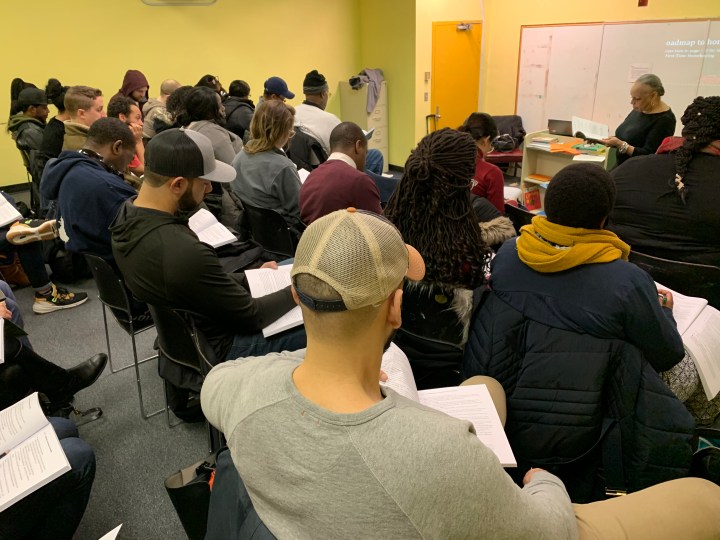

But on a recent rainy Thursday night, nearly every chair in a third floor classroom of the community center was filled for Homebuying 101, a class for low- and middle-income people who are looking to buy for the first time in the Boston area.

“Because of what I do, I would hate to say no, that it’s not affordable anymore,” said Linda Warren-Cato, who has been teaching classes like these for more than 20 years.

“What I tell people every time I teach the class is that you just have to find a property that your income will support. And you can’t give up, because there are a whole host of ways that you can potentially find a property.”

She believes that’s true even in this city that, for 20 years now, has been one of the most expensive places in the country to buy, and is only becoming more so. As of 2018, the median home price in the Boston area was more than five times the median household income, according to the Greater Boston Housing Report Card of 2019, making it the fourth most expensive metropolitan area in the country to buy, after San Francisco, Seattle and New York. These days, buying a home in the Boston region, as in much of the country, is unaffordable for the average person.

Buying in the city itself has already become “almost unattainable for a person of low to moderate, even middle income,” said Elliot Schmiedl, director of homeownership for the Massachusetts Housing Partnership.

“Then the number of suburbs that circle Boston that are affordable to this degree is just dwindling. Take Quincy as an example. Quincy used to be a working class community outside of Boston where you could go and find a place, reasonable cost, you could get in and out of the city. That’s not the case anymore. You’ve got to go down to Brockton, you’ve got to go 20 miles south.”

Half an hour before the first session of Homebuying 101, in early February, David Glass was already in his seat in the front row. At 63, after a lifetime of renting, he is now in the process of trying to buy for the first time. He got married three years ago and his wife, he said, “feels more secure with a home.”

When they first started looking into getting a mortgage, though, “we were told we couldn’t even be helped unless we could qualify for $450,000,” said Glass, who lives in Dorchester and currently works as a truck driver. “It’s terribly insane, but it’s the reality. And that’s the scary part, you know, your mortgage payments are going to be high.”

Rent in Boston is high, too, though — the median rent for a two-bedroom in the city is $2,500 — so instead of giving up on the idea of buying, they’ve decided to try a different avenue, and go through the affordable housing lottery in the city.

“Of course you have to get lucky,” Glass said, “but I think that a lot of people that think they’re ready are not ready, so that list can shorten up very easily.”

To qualify to buy through the lottery, Glass and his wife have to complete this eight hour homebuyer education class, broken up into two-hour sessions over four weeks. The curriculum, which is taught multiple times a month all across the state, in English, Spanish, Chinese, Khmer, is approved by the Massachusetts Homeownership Collaborative, and has been around since the mid-1990s. People who complete it are eligible not just for the affordable housing lottery, but for other forms of assistance, too, through the city or the state, from mortgages that only require 3% to 5% down, to financial help with a downpayment.

“Someone making $100,000 in Boston qualifies for assistance, either an affordable mortgage or physical downpayment assistance, so our class is geared towards those people,” said Jacqueline Cooper, the president and executive director of Financial Education Associates, one of the organizations that teaches Homebuying 101. “Pretty much in Boston you can get help for even up to $150,000 and under. That’s my target market. To let people know, first of all, that there is help. Don’t sit around waiting until you can get the 20%.”

When Cooper, who was born and raised in Boston, first started teaching these classes in 1996, “affordability was not so much the issue as much as people fleeing the city,” she said. “They started it to provide an incentive for first-time homebuyers to purchase homes in the city.”

Now, as people have come back to the city in droves and prices have skyrocketed, the classes are largely about helping “regular people,” as Cooper calls them, figure out how they can afford to stay, and buy for the first time.

It is getting harder, though. There’s no way around it. Both rents and home prices are rising faster than salaries, and there is not nearly enough new housing being built to keep up with demand. The gap between the rich and the poor is only getting bigger in the region, too, as it is around the country. Between 1990 and 2014, the number of high-income households in the Boston area increased by 43,000, and the number of low-income households increased by 30,000. Over that same period, the number of middle-income households fell by 15,000.

That increase in income inequality, the Boston Foundation wrote in its 2019 housing report card, “can exacerbate a region’s housing affordability problems. Higher income households will always be able to outbid lower income residents. If production is not able to keep pace with demand, then middle-income households will struggle to find affordable options on the market, and low-income households may be pushed out of the market altogether.”

Both Cooper and Warren-Cato, who have been friends since they were kids, feel like it is their mission, their purpose, to help low- and middle-income families find ways to buy so they don’t get pushed out.

“I think the most important reason for people to make this shift is the security. I can’t tell you how often I run into people, because of what I do, that are fearful that they’re not going to be able to stay where they are,” Warren-Cato said. “For the majority of the people that I see it’s all about, ‘I want something that nobody can take away from me.’”

She knows, first-hand, how life-changing it can be to have that.

“I came from a single parent household. My mom struggled. I was the first person in our nuclear family to go to college. I was the first person to actually buy a property,” she said. A condo she saved up for for seven years.

Her sisters now own homes, too, and she got her mom into one at 55. Her mom, who had always said she’d probably die before she ever owned a home.

“Her mortgage is $194.88. Her condo fee is $257,” Warren-Cato said. “She never, ever thought about buying anything. But I saw what a difference it made in my personal life, my family’s life, and I want everyone to have that aha moment.”

Given the reality of today’s market, Cooper said, people may need to adjust their vision. Think about buying a condo, instead of a single family. Buying with a family member, instead of alone. Buying just outside the city, instead of in it.

“I think how people previously thought about housing, that they would own this big house, that may not be possible if you still want to live here,” Cooper said. “But there will be maybe opportunities where you can still buy here. It’s just not going to necessarily look the way you thought it was going to look.”

Low- and middle-income people are still buying, according to Schmiedl, who oversees ONE Mortgage, one of the programs people can qualify for by taking Homebuying 101.

“Our loan volume isn’t lower than it used to be,” Schmiedl said. “Our city of Boston loan volume has gone down. So you know, Jackie might have done a class 10 years ago, and if five out of 10 people in that class bought a home, maybe the majority were in Boston. But nowadays they’re moving further out.”

David Glass is very much hoping that, through the affordable housing lottery, he and his wife will be able to stay in the city.

“I would like to stay in the Dorchester, South Boston area, but that’s not etched in stone,” he said.

Whatever neighborhood he ends up in, whatever kind of place he and his wife are able to buy, just thinking about owning something “feels like an elevation,” Glass said. “It feels like you’ve arrived, and after years of blood, sweat and tears that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.”

The one thing he does know is he wants to stay in Boston. The city he’s lived in and worked in, as a construction worker, for much of his life.

“I helped build Boston actually,” he said.

It’s home. And expensive as it has become, he and his wife are determined to stay, hopefully as homeowners.

“We feel as if, there’s no such thing as entitlement, but certainly we’ve worked hard to be in this position,” he said. “I feel like we deserve to stay.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.