Is this controversial weedkiller helping or hurting our food supply?

Share Now on:

Is this controversial weedkiller helping or hurting our food supply?

The fate of a controversial chemical weedkiller that has pit farmer against farmer remains in legal limbo, but on American farms the herbicide will likely remain in use through the growing season, industry analysts and researchers told Marketplace.

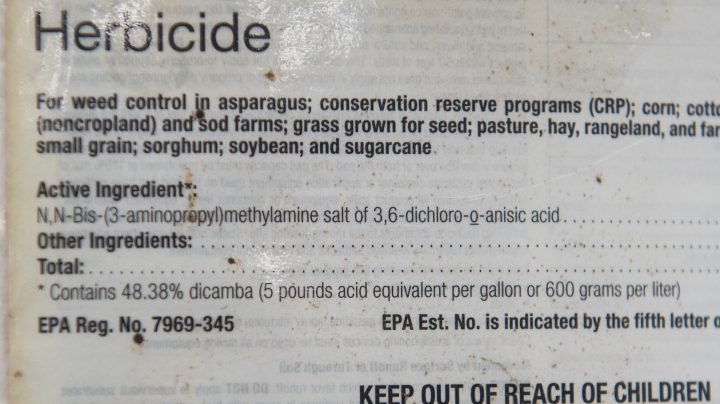

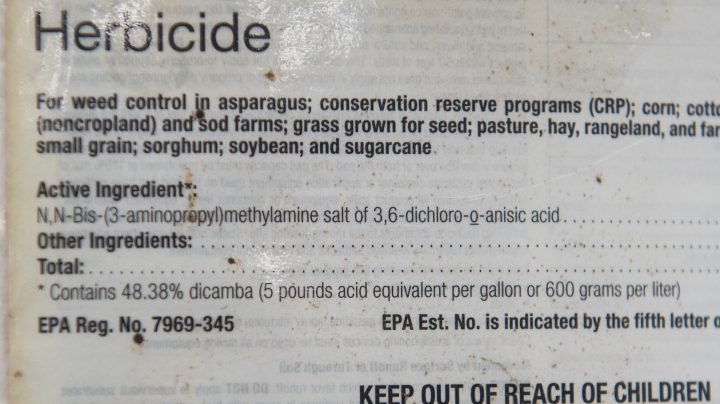

That means the blockbuster herbicide dicamba, which critics complain can’t keep its agricultural social distance — drifting into neighboring farms and killing harvests — and has, in one court’s words, “torn apart the social fabric of many farming communities,” will keep dividing farming towns and consumers. Many critics and scholars also fear continued use of dicamba will keep American farmers engaged in a toxic chemical arms race against ever-adaptive weeds.

The concern for consumers: that adaptive weeds could someday outrun herbicides, sabotaging future harvests and America’s food supply. Herbicide manufacturers and proponents counter that chemicals like dicamba keep yields high and prices low today.

The immediate issue: a June 3 federal appeals court ruling nullifying the Environmental Protection Agency’s approval of dicamba products, citing “fundamental flaws” in the EPA’s process of vetting the product’s risk of drifting.

Several legal turns later, the dicamba controversy remains mired in uncertainty, regulatory minutiae, advanced chemistry and dueling narratives. In other words, the weeds.

So to step back, we begin with something called pigweed.

Pigweed

Pigweed, as its name suggests, is a demonstrably stubborn weed that has long vexed American farmers. Also known as Palmer amaranth, pigweed grows 2 to 3 inches per day in the South. It reproduces prolifically. How do you solve a problem like pigweed?

The leading approach to date: chemicals. In the 1970s, Monsanto introduced the herbicide glyphosate, a broad-spectrum product commonly known as Roundup, which was so effective it became a weed killing hit. Then in the ’90s, genetically modified Roundup Ready – or herbicide-proof — soybeans and cotton seeds came onto the market, allowing farmers to spray glyphosate, kill weeds and leave crops unharmed.

Then pigweed adapted. After a decade of widespread Roundup use, Purdue University researchers found the invasive plant developed resistance and fought back. Pigweed infestation reduced soybean yields by up to 79%, and as much as 91% in corn.

Monsanto returned with a next chemical: dicamba, an older herbicide that nevertheless wiped out pigweed. And just like glyphosate, farmers using dicamba paired it with special genetically altered dicamba-resistant seeds.

“Dicamba is like a hammer, it’s powerful,” Stan Born, a central Illinois soybean farmer and board member of the American Soybean Association, which supports farmers’ continued temporary use of dicamba this season, said. “It’s very good at controlling difficult-to-control weeds. And it’s nice to have that tool, because sometimes you need it.”

“We are proud of our role in bringing innovations like these forward to help growers safely, successfully and sustainably grow healthy crops,” Bayer, which acquired Monsanto in 2018, stated in a June 11 release. “Bayer stands fully behind our Xtend [dicamba] System.”

But dicamba came with a catch, a liability that stands at the center of farmer disputes and the current litigation: It can drift.

Chemical trespassing

Dicamba is volatile and blows with the wind. It can move easily off a field after being sprayed, notably in hotter temperatures. Weed scientists call this “chemical trespassing.”

“I have never seen a herbicide that has so easily and frequently slipped the leash,” Larry Steckel, professor and row crop weed specialist at the University of Tennessee, told Delta Farm Press in a statement cited by the court. “Dicamba drift for the past three years has often travelled a half mile to three-quarters of a mile and, all too frequently, well beyond that.”

“I have never seen a herbicide that has so easily and frequently slipped the leash.”

Larry Steckel, University of Tennessee weed specialist

This drifting means dicamba can float over to a neighboring farm, harming crops that don’t enjoy bio-engineered protection.

After the EPA first approved dicamba for use in late 2016, complaints of herbicide drift shot up, according to statistics from agricultural regulators cited by the court.

Drift “will cause the growth buds to potentially shrivel,” Rob Faux, an organic farmer in northeastern Iowa and member of the anti-dicamba Pesticide Action Network, said. Faux described himself as a victim of drift, yet doesn’t know which neighbor is at fault. “It’s not uncommon to harvest 6,000-7,000 bell peppers in a season. Two seasons ago we harvested seven peppers. Seven.”

“It’s not uncommon to harvest 6,000-7,000 bell peppers in a season. Two seasons ago, we harvested seven peppers. Seven.”

Rob Faux, Iowa organic farmer

In 2017 a dispute between two farmers along the Arkansas-Missouri border — one spraying dicamba, the other not — led to an in-person confrontation that ended in the shooting death of Mike Wallace. Defendant Allan Curtis Jones was convicted of second-degree murder.

Farmers have also taken fights to court. In February of this year, a Missouri peach farmer won a $265 million verdict against dicamba producers Bayer (which acquired Monsanto in 2018) and BASF, on grounds that their dicamba weedkillers harmed his orchard. The companies said they plan to appeal. In the current case that technically outlaws dicamba, food safety and farm groups sued the EPA, challenging its 2018 approval of dicamba-based herbicides.

“The EPA substantially understated the risks it acknowledged, and it entirely failed to acknowledge other risks,” the ruling from the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals stated.

More than 100 other cases remain in the pipeline.

But its still being sprayed

Following the ruling to undo EPA’s approval of dicamba products, the agency argued farmers can keep spraying through July 31. It stated farmers “already in possession of” the product can continue to use it. The petitioners challenging the agency have asked the court to enforce its ruling immediately “and find the EPA in contempt.”

For now, farmers are following the agency’s lead and continuing to spray, Hartzler of Iowa State said. “Since EPA is responsible for enforcing the Pesticide Act, almost everybody involved in agriculture is interpreting that it’s good to go,” he said. “State departments of agriculture are on board.”

And by the end of July, the time frame suggested by the EPA, the spraying season in the country will be largely over.

“The ruling came so late in the planting and crop chemical application season that for all practical purposes it’s going to have a small impact on 2020 use of dicamba,” industry analyst Christopher Perrella at Bloomberg Intelligence said.

“For all practical purposes its going to have a small impact on 2020 use of dicamba.”

Christopher Perrella, Bloomberg Intelligence

Whatever the legal outcome of jousting between the EPA and the appeals court, federal approval of dicamba products runs out in 2020 anyway. So manufacturers would have to submit new applications to EPA, in which case the could vet the applications in a way that passes court muster.

“EPA can make a new decision in the future that doesn’t have the same flaws,” said William Jordan, former EPA deputy director in the office that oversees herbicide regulation. “So EPA gets another at-bat.”

Back on the herbicide “treadmill”?

Which returns us to pigweed. The stubborn invasive plant is a key reason agribusiness giants and farmers want to keep dicamba on the market into 2021 and beyond. That bring risks, of further discord between farmers and lawsuits, and of pigweed adapting to dicamba and developing resistance.

That may already be happening. University researchers in Tennessee and Kansas suggest this “superweed” is already demonstrating some resistance to dicamba. If dicamba, like glyphosate before it, becomes increasingly ineffective against pigweed, farmers dependent on a chemical solution would need to find a next herbicide. “All the seed companies are working on other ones,” Perrella of Bloomberg Intelligence said.

Dicamba proponents also note that farmers can extend the life of the product by rotating herbicides and only spraying dicamba when needed. “Keep the weeds confused,” Stan Born, the Illinois soy farmer, said.

Still, skeptics wonder how long this cycle of chemicals and weed resistance can sustain. Will the herbicides always stay ahead of the race? Agricultural economist and consultant Charles Benbrook said the cycle is expensive, as agribusiness giants pass along the costs of their research to farmers and ultimately their customers.

“They pay four times more for the seed, and herbicide costs are going through the roof,” Benbrook said. “They are caught on what weed scientists call ‘the herbicide treadmill.’”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.