The coronavirus has highlighted the transit inequalities in America

While many office workers were able to shelter-at-home during the height of lockdown orders across the U.S., many other employees trekked into hospitals, supermarkets, warehouses, and transport depots to keep vital services running. And many of them relied on bus and train systems.

Transit ridership plummeted around 90% at the peak of the pandemic, and journeys for the remaining 10% of riders started becoming more difficult. Services were cut, both to protect drivers and other transit workers, but also because transit systems are running out of money, in a situation that’s becoming acute.

Fare revenues dropped to near zero. The busses that were running were often not collecting fares to allow passengers to board through the back doors and stay distanced from drivers. Local sales taxes plummeted, wiping out another vital source of funding for transit agencies, along with money from parking tickets and fines.

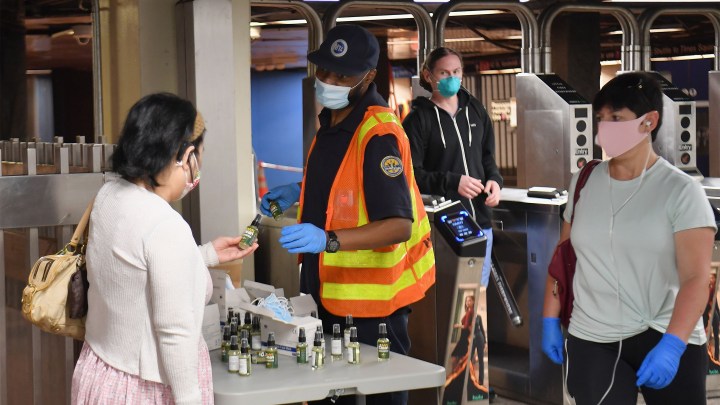

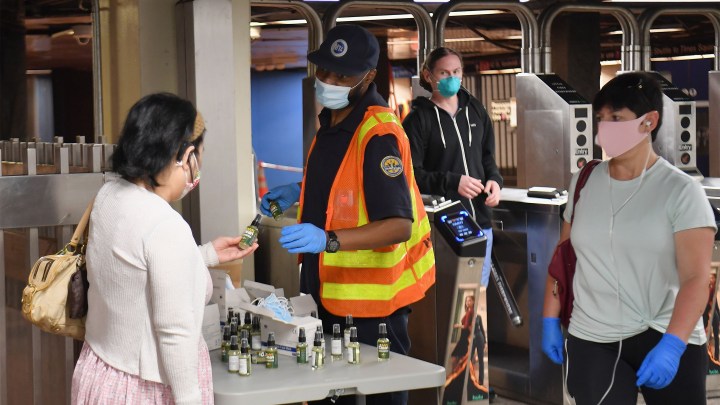

At the same time, agencies are still having to fund extra expenditure like cleaning stations and running vehicles at reduced capacities.

“It’s really thrown transit agency budgets for a loop,” said Benjamin Fried at the TransitCenter, a nonprofit organization that advocates for better public transportation.

Weathering the transit crisis

Agencies are now in crisis mode, trying to figure out how to balance the books, keep essential workers moving, and still have a long-term view on building systems that can make cities better integrated and more equitable.

Amid the difficulties, advocates see an opportunity for building better systems in the future, and are including those plans when asking for more federal funding to weather this downturn, in a House bill.

Congress previously provided an unprecedented $25 billion as part of the CARES Act of pandemic support measures. “The CARES Act was incredible,” said Scott Goldstein, policy director at Transportation for America, a national nonprofit.

“It essentially saved public transit.” It’s not enough, though, he says.

Transit as an essential service

There’s a wide variety of transit, and transit riders, across the U.S. In some metropolitan areas, particularly on the East Coast, people from all socioeconomic backgrounds use busses and subways. In New York City, jumping on a train is a standard way of getting to work.

“And then you have other places where transit is more of a social service, used exclusively by people of lower income,” said Fried. For many, busses are the only way of getting to a supermarket, or a doctor’s appointment, and as the pandemic has revealed, for getting to work.

As the U.S. is having a national conversation about inequality, access to transport is a fundamental part of the equation.

A 2017 study by the University of Southern California found that low-wage workers who did have access to a car in San Diego had access to more than 30 times the job opportunities that those who relied on public transport.

“The pandemic has revealed how essential transit is for many workers,” said Harriet Tregoning, director of the the New Urban Mobility Alliance, a collaborative that aims to guide policymakers, and the private sector, at the World Resources Institute. “It’s critical that we look at how we’ve built our cities and arranged our transportation to stop disenfranchising this population.”

Rethinking and rebuilding better

Some agencies have used the challenge of the pandemic as a chance to experiment. Oakland, California, championed “slow streets” which encourage biking and walking. Muni, in San Francisco, was agile in its responses to falling ridership numbers, and was able to concentrate a limited service on high demand corridors, rather than just falling back on a low volume “weekend” timetable like other cities. That meant riders on 17 key routes got fast, dependable, service on busses that weren’t overcrowded.

This might be an opportunity to think about whether transit should be provided with operating support in general,” Goldstein said. Given how essential the service is, long term, federal, support through funding, rather than just emergency measures, would be a meaningful investment in communities.

Bigger overhauls, which have been under consideration, or even used in limited trials, could now be accelerated. That includes using smaller vehicles, and scrapping fixed routes and schedules for on-demand services, according to Tregoning. In effect, combining the advantages of ride-hailing with those of busses.

Large employers and transit agencies could work together to stagger shift times, to reduce crowding. Longer term, the location of key businesses near affordable housing can reduce transit reliance, and better urban planning can help alleviate the rush-hour migration all in one direction, making it more dispersed, and reducing empty carriages and busses in one direction at certain times of day.

Big changes would require reliable funding — which is by no means guaranteed — but advocates say this is an opportunity for a reset, and rethink, of how transit serves the communities it operates in.

The biggest crisis of all, for transit reform advocates, would be for people to follow through on what many say they are contemplating: buying a car. “That would just pile on to the trouble that transit is already facing,” said Fried.

Increased vehicle traffic in cities could unwind decades of efforts to make transit more usable by further reducing ridership and revenue, and clogging streets making busses even slower.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.