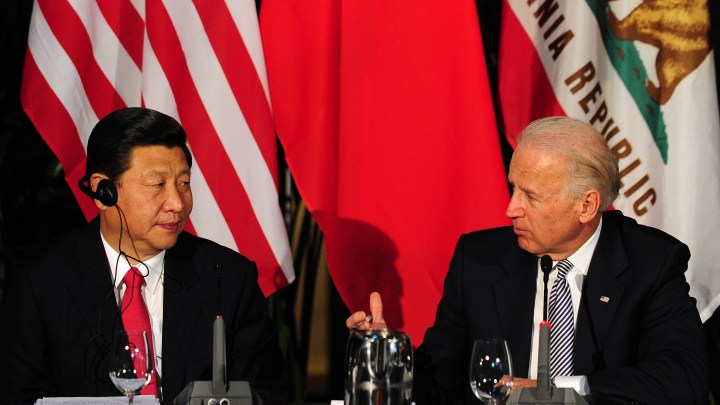

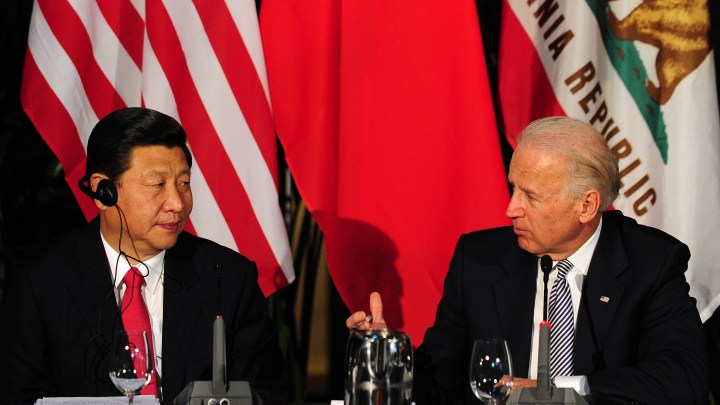

Biden’s China options

Market access, intellectual property theft, forced technology transfer, subsidized Chinese companies. The U.S. holds a long list of grievances in its trade relationship with China. A Biden administration will inherit a range of policy tools, and be denied others, at least in the beginning.

“One really useful option of confronting China has been taken away, and that is to be able to use the World Trade Organization to be able to bring cases against China,” said Chad Bown, a senior fellow with the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“For the previous 10, 12 years, that had been the approach. And virtually every time one of those disputes were brought forward, and there were two dozen or so of these the United States brought against China, the U.S. would win the case. And China, for the most part, would fix the underlying problem.”

But the Trump administration blocked judges from joining the bench there, basically shutting down the ability of the WTO to settle trade cases.

The Biden administration could reverse that.

Then again, even when the WTO was functional, it didn’t put a stop to one of the U.S.’ major complaints with China: subsidies.

WTO rules require countries to publish a list of the subsidies they offer domestic industries, but enforcement of that requirement has been poor, according to Nick Lardy, also a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute.

“The rules on subsidies are vague,” he said, “and as a result there have not been very many cases dealing with subsidies.” Cases at the WTO — over everything from airplane subsidies to unfair dumping of products — can drag on for years, and by the time they’re resolved, a lot of economic damage has been done.

There are, of course, tariffs. A favorite of the Trump administration, they already cover $350 billion worth of Chinese goods, and have provoked retaliatory tariffs on half of what the U.S. sells into China. “The tariffs have not induced any kind of positive change and, in fact, the evidence is they’re hurting the U.S. economy,” said David Dollar, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

While Trump’s tariffs haven’t produced structural change, they might afford President Biden at least some leverage for getting rid of them, he argued. “The smart thing would be to negotiate away the tariffs in return for clear progress on market access, intellectual property rights protection, forced technology transfer,” Dollar said. History suggests that’s easier said than done.

Another strategy open to Biden: targeting specific Chinese firms on national security grounds. That was another favorite under the Trump administration. “I think a Biden administration is absolutely going to need that policy,” said Amy Celico, a principal with Albright Stonebridge Group.

If a trade dispute is cast as a national security issue — and there can easily be a lot of overlap — a president or a country can gain a lot of legal leeway.

“When it comes to national security interests of the United States, having access to medical supplies, having access to rare earths that, as you know, are essential components in so many IT systems,” Celico said.

Trump, for example, blacklisted Chinese telecom company Huawei. The administration tried to cut off its ability to benefit from U.S. technology and even tried to scuttle Huawei’s deals with governments abroad.

Celico says this wasn’t simply because of national security concerns — the U.S. also views Huawei as having received unfair support from the Chinese government and having taken the intellectual property of its competitors.

Blacklisting as a policy can invite other problems — China can harass U.S. companies in return. It has a list of “unreliable entities,” that it can use to upend a firm’s operations in China.

There’s one approach that fell out of favor under Trump administration: simple strength in numbers.

“Start building a club of like-minded economies,” said Brookings’ David Dollar. Many countries have the same issues with China as the U.S. does. Together, they could change the rules at the WTO for example.

Dollar said the U.S. needs to rebuild and build ties with Asian countries, and rejoin the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement. That deal, negotiated under Obama and abandoned by Trump, doesn’t include China and sets a high bar on issues like protecting intellectual property.

“If we are creating a better set of rules for innovation and efficiency, then that’s going to tend to win out as the home for important supply chains,” he said.

Whatever path the Biden administration treads, the reality is that China’s economic clout keeps on growing. And none of the available tools is a silver bullet for managing the relationship between two economic superpowers.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.