Farmers in Texas still reeling from the February freeze

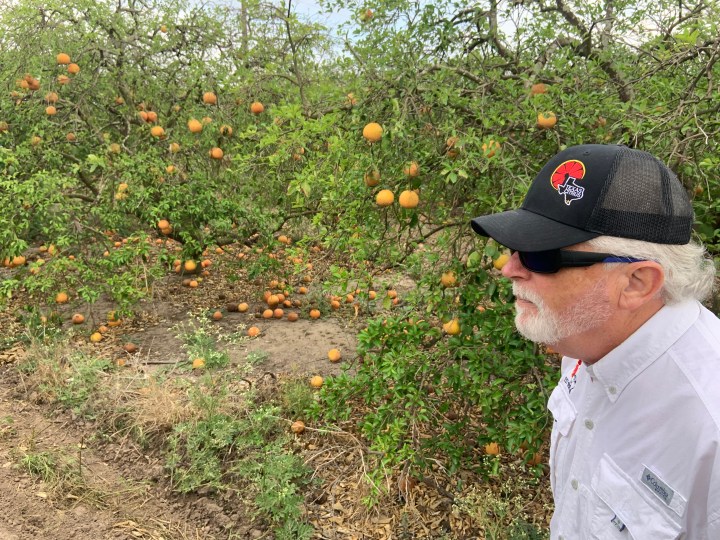

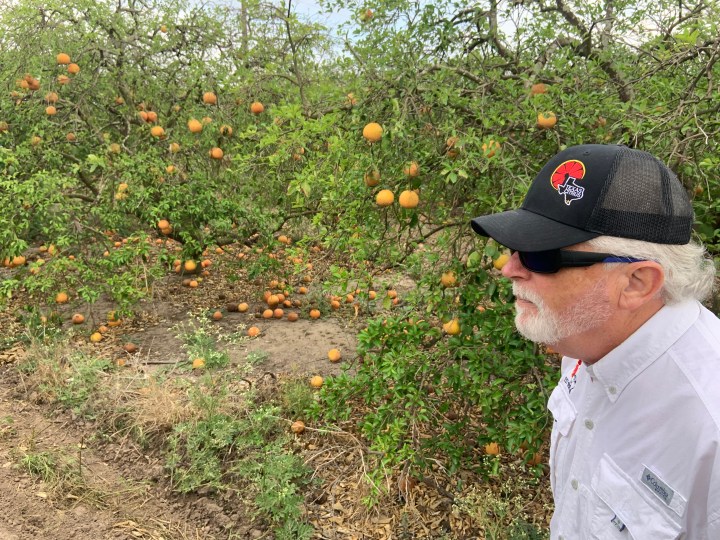

Dale Murden owns a couple of citrus groves along state Highway 107 south of Harlingen, Texas.

Murden’s been trying to figure out how much of his harvest he can claim as a loss ever since February’s storm walloped normally warm places with ice, snow and frigid air, killing more than 100 people in Texas and leaving millions without power for days.

“I’m one of those that had 50% coverage,” Murden said as he pulled out his phone to take pictures of tree damage. “What that means, basically, it’s your deductible is 50%. So if you don’t have a 50% loss, you don’t even trigger. That’s what a lot of people don’t understand about insurance … it never makes you whole.”

There’s a lot of fruit on the trees in Murden’s groves, but that fruit was frozen, so it’s worthless. At the same time, his trees are starting to show signs of new growth.

“See those little balls there?” he asked as he pointed to a tree branch. “That’s a little tiny grapefruit you’re looking at.”

Lost crops, lost income

Murden is encouraged, but those little buds certainly won’t be ready to harvest next year.

“Technically I’ve lost two crops,” he said. “The one that was being harvested for the 2021 season, and now zero crop for the 2021/2022 season. Yes, the trees are growing back and that’s great. But I won’t have any income until the 2022/2023 season.”

As president of Texas Citrus Mutual, a group that lobbies for the interest of Texas citrus growers, Murden said the industry as a whole might only produce 20% of the normal grapefruit crop next year.

“It all gets back to the grower,” he said. “What’s he willing to spend for 20% of our crop? We’re gonna do everything we can to get the trees healthy again. But man, that’s expensive.”

South Texas aftereffects

Farmers who grow other crops in south Texas are also dealing with the aftereffects of the freeze.

Trevor Stuart at Frontera Produce in Edinburg said just how much farmers are suffering has to do with what they were growing.

“Dill, cilantro, all your parsley, your beets, your Swiss chard, your lettuces, your celeries, that stuff was completely smoked,” Stuart said.

Frontera grows a bunch of crops and sells them to retailers, but Stuart said Frontera made out relatively well. It lost its first cilantro crop, but that grows back pretty quickly, and the onions mostly survived.

In a cavernous packing plant with an overwhelming onion smell in the air, machines sort the harvest. The plant floor is full of Frontera workers driving front loaders scrambling to get the onions out to delivery trucks.

Onions tested

“We are writing the book on how these specific onions will handle cold temperatures because these varieties that have been around whether it’s five years, 20 years, 30 years have never been tested like this year,” Stuart said.

Back in Harlingen, citrus grower Dale Murden’s feeling tested himself these days. He said he’s really counting on that insurance money and that he’s even considering selling the land. He’s in his 50s and he said his kids are not interested in taking over.

“There will definitely be groves removed,” he said. “And, you know, down here in the valley, the growth is so phenomenal, it’s either gonna go subdivision or, you know, in my case, I would hope that people go back into agriculture. Once you put something in concrete, it’s kind of forever.”

For now, he’s just concentrating on nurturing his grapefruit trees back to production.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.