With long-term unemployment comes long-term challenges

Forty-three percent of jobless American workers are long-term unemployed, meaning they’ve been actively looking for work for more than 27 weeks (a little over six months), according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ April jobs report.

That’s nearly as high as the peak following the Great Recession, when long-term unemployment hit an all-time high of 45.2% in September 2011. And it is nearly twice as high as the peak in long-term unemployment in any other recession dating back to the late 1940s.

And while there has been a dramatic recovery in employment following the mass layoffs early in the pandemic in spring 2020, many service-sector employers have yet to reopen and rehire, and millions of former workers remain on the sidelines either not working or not yet looking for work. That leads many economists to warn that elevated long-term unemployment may persist for years after the pandemic recession is behind us.

High long-term unemployment will likely persist

“It is likely to be even longer and more problematic than the long-term unemployment that was so catastrophically associated with the Great Recession,” said labor economist Arthur Goldsmith at Washington and Lee University, who has studied the mental health effects of unemployment in different racial and demographic groups.

And economist Peter Cappelli, director of the Center for Human Resources at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, said the economic impact will likely linger for many who eventually do find work again.

“It’s really difficult for people — particularly those who’ve had a lot of tenure with an employer — to ever get back to the kinds of jobs and pay they had before,” he said.

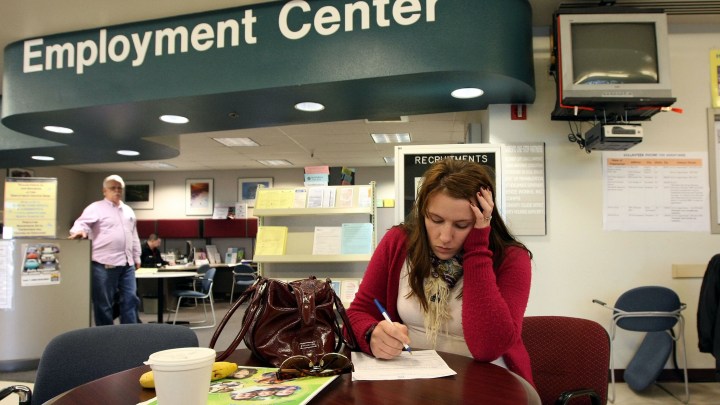

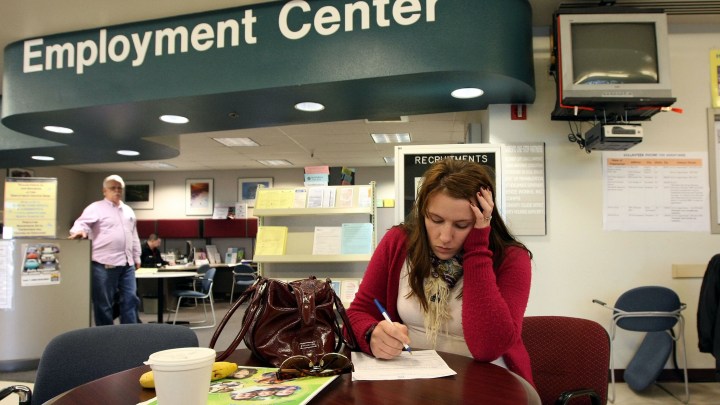

McKenna Brock is among the pandemic-era long-term unemployed. With a freshly minted master’s degree in public policy, the 26-year-old native of Tucson, Arizona, has been job hunting for more than a year.

“Some days I sit down and go through 20, 30 applications,” Brock said. “I’m happy to go wherever there’s work, but the problem is that there isn’t much work. Or that I’m not finding it.”

Brock has landed some interviews, but no job offers. When she asks for feedback from potential employers, she often hears that someone with more experience got the job.

“I have a sense that people who lost their jobs in the beginning of the pandemic are applying for these more junior roles, and obviously, someone’s going to hire a very experienced person and pay them less if they can,” ” Brock said.

“You start to doubt yourself”

“You know, when you get constant rejection, over and over and over again, it does start to feel a little bit deflating,” Brock continued. “You start to doubt yourself — something I’m doing isn’t working right.” And she’s aware that a lot of people are going through the same thing: “Like my mom — she’s got years of marketing experience, and she can’t find a job.”

That’s Tiffany Brock, 54, who was laid off from her job managing national beverage sales for a company in Tucson back in June 2020.

“I’ve got a great resume. I have great experience,” she said. “And I started applying. Unfortunately, so did everyone else.”

Some jobs she applied for had thousands of applicants. She found some of the process humiliating.

“They didn’t even start interviews until after you wrote essays in why you wanted to work for the company,” she said. “They wanted videos demonstrating your best career moments.”

Stigma is the first challenge

The first challenge long-term unemployed people like the Brocks face, said sociologist Ofer Sharone at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, is the stigma of long-term unemployment. His research finds that when employers are presented with job seekers with similar qualifications and experience, they are just half as likely to interview the candidate with a significant employment gap on their resume.

And Sharone said the stigma extends to job seekers and the people they know, too.

“There’s a tendency for job seekers to internalize the stigma, to have fears that ‘Yeah, maybe something is wrong with me,’” Sharone said. “And in former [work] colleagues, there’s also the same kind of stigmatized response of suspicion, of the person’s long-term unemployment being a red flag.”

All this can lead, said Denise Rousseau, a Carnegie Mellon University organizational psychologist, “to a loss of confidence, a high level of anxiety with looking for employment, interviewing, reentering the workforce. And that tends to be a self-perpetuating cycle, that once you begin to doubt, you doubt more.”

Support and counseling

The first order of business in helping the long-term unemployed, according to Sharone, is to connect them with support and solidarity groups and counseling: “Recognizing that not only does it take a long time to get a job, but people may be feeling shame. Addressing that head-on, and then start to talk about strategy, and networking and resumes.” Sharone’s research stresses shifting blame and responsibility for long-term unemployment from the unemployed worker to sociological and structural causes of unemployment in the economy.

Rousseau said that as employers staff up again, they would do themselves a favor to tap current employees to recommend their unemployed friends for jobs.

“People who have friends in an organization where they’re being hired are more likely to be successful and to be retained in that organization,” she said.

Public policy has a role to play, too. Sharone argues that government should bar employers from discriminating against the long-term unemployed, just as they enforce bans on race, gender and age discrimination in hiring.

Linking schools with employers

Peter Cappelli said government-directed retraining programs have a poor track record getting large numbers of people reemployed and earning comparable wages again. Instead, he suggests going hyperlocal, linking schools with employers.

“You could say, for example, ‘Let’s figure out what these small group of employers in this town really needs and what they really think they’re going to be doing in the next year or two,'” Cappelli said. “Let’s not try to plan 10 years out, because it just doesn’t work.”

Cappelli said providing tax credits to employers for hiring unemployed people, to discourage them from poaching workers who already have jobs from other employers, could also help reduce long-term unemployment.

For her part, Tiffany Brock is more worried about her daughter McKenna’s long-term unemployment and career prospects than her own. She doesn’t feel much stigma about being out of work for the past year because the pandemic took her job.

“It feels like you have permission to be unemployed,” she said. “Obviously, being let go wasn’t based on my performance or ability to help the bottom line. It truly was a condition of nature, right?”

Correction (June 3, 2021): A previous version of this story incorrectly described the group of long-term unemployed Americans from April’s jobs report. The text has been corrected.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.