Chinese students, parents stressed by demands of extracurricular classes

Chinese students, parents stressed by demands of extracurricular classes

Wan Changru’s eldest daughter is unusual among Chinese school kids. The Beijing student does not attend extra classes in English, Chinese or math.

“There is a lot of anxiety when other students are attending extracurricular classes during the winter break, but my child did not. I was worried,” 46-year-old Wan said. “But extracurricular courses cost more than 100,000 yuan [$15,600] a year. I just can’t afford them.”

The stress of educating children was one of the reasons young married couples were unenthusiastic when the Chinese government recently announced that parents will be allowed to have three children, up from a maximum of two.

Officials have tried to ease the burden on families by cutting class hours, reducing homework assignments, making tests easier and banning the ranking of students. Ambitious parents responded by enrolling their kids in extracurricular classes to help them stand out from their peers. Then, in recent months, China’s government started tightening regulation of the tutoring industry and fined some companies in it for preying on anxious parents.

An estimated three-quarters of China’s students from kindergarten to grade 12 attend extracurricular classes.

Annual revenue for the tutoring industry exceeds 800 million yuan ($125 billion), according to the most recent estimates.

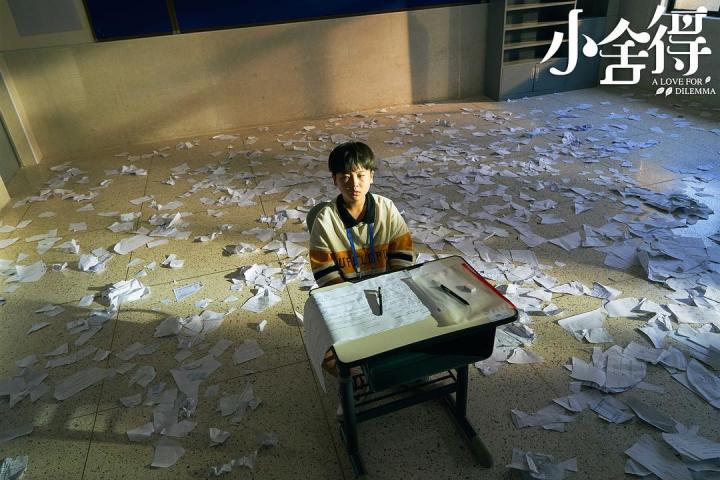

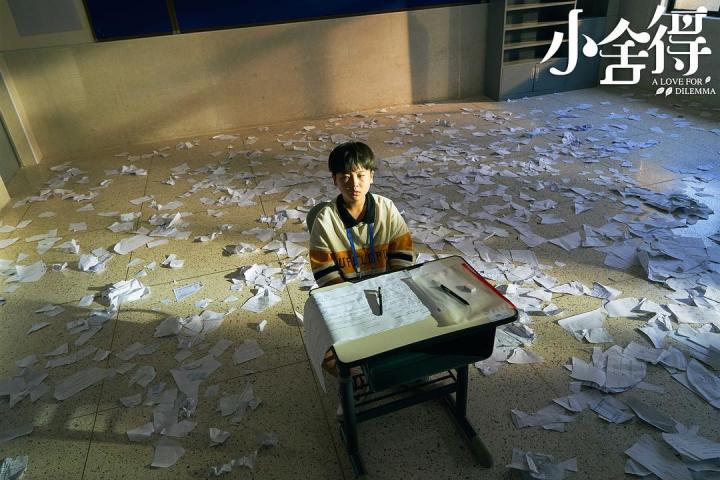

A top-rated TV series this year, “A Love for Dilemma,” is about the education rat race.

The show focuses on two stepsisters: Tian Yulan, who packs her son’s schedule with extra courses in math, English and Chinese; and Nan Li, who has never enrolled her child in extracurricular courses and prefers that her fifth-grader have play time and get modest grades. Eventually, Nan Li caves to societal pressure and tracks down a top tutor in a forest. The tutor is shrouded in mystery. He never reveals his face and changes venues for every class. Parents seek him out because he only accepts top students.

In China, even ace students have tutors just to get extra points on exams.

“My daughter is in the best class in her high school and the teacher requires the average score to be 98%,” Wan said. “Of course, this is a rigorous requirement, and the teacher said it is abnormal, but every point counts.”

China’s government controls the ratio between those who enter senior high school and students who go to vocational schools. In 2019, 60% of ninth-graders were accepted into senior high schools.

Wan’s ninth-grader is up against millions of others.

“I just ask my daughter to follow the teachers’ instructions. If she studies well, there is no need to send her for extra tutoring,” Wan said.

Rat race

The competition starts early in kids’ lives.

There is a scene in “A Love for Dilemma” in which the lead character’s son, Chao Chao, meets a 2-year-old girl who speaks English.

“Hi boy. What’s your name? How old are you?” she says.

Chao Chao looks confused. By way of a response, he hands her a candy.

In China, children only learn English in school starting in grades 1 or 3.

“I hired a one-on-one English tutor from the U.K. for her when she was 8 months old,” the little girl’s mother says.

The girl wasn’t even able to speak yet, but the mother hoped the tutor would help her child speak English as fluently as Chinese.

Exhausted parents

Wang Wenjing, lives in a small city in eastern Shandong province and does not send her child to outside classes.

“The quality of the extracurricular courses that I know of is not worth the price,” she said.

Instead, she teaches her daughter on her own.

“Here is our plan: One day I teach English, the next day Chinese. Once I am finished, then her father teaches her math,” Wang said.

At first, Wang’s daughter did not like learning English.

“But one day, maybe because her teacher at kindergarten asked her to teach the other children some simple [English] words and she felt a sense of achievement,” Wang said, “she began to like [learning] English.”

These days, Wang’s 5-year-old can watch English cartoons and explain them to her mom.

Wang admits she is not the best guide. She doesn’t speak English well herself, but she is trying.

“There are many English words I don’t know, so I have to study first before teaching my daughter,” she said.

Her daughter ends up studying an extra three hours a day.

“My husband and I are both educators. This kind of training for my 5-year-old is hard even for students in grade 2 or 3, but she won’t feel the pain after getting used to it.”

Wang understands the competition her daughter will face coming from a small town.

She and her husband are their families’ first university graduates. In the early 2000s, when Wang applied to college, top schools like Peking and Tsinghua universities accepted only one of more than 7,000 applicants from her home province of Shandong.

Wang is preparing her child for the endless competition she’ll face in the school system.

“This kind of training for my 5-year-old is hard even for students in grade 2 or 3, but she won’t feel the pain after getting used to it.”

Wang Wenjing

She hopes her only child can enter a top college.

“Elite universities are definitely different from ordinary universities,” Wang said. “When I recruit people for my business, I can feel the difference in graduates from an ordinary university versus a top school.”

How far can you push a child?

Students say they are tired too. Wan said her eldest daughter’s only hobby is sleep.

“She likes to dance, but she is not allowed to develop her hobbies because she does not have time,” Wan said.

In a poignant scene in “A Love for Dilemma,” fifth-grader Ziyou stands up during a parent-teacher conference to confront his mother.

“I don’t think my mom loves me. She only loves the me that gets 100%,” he says.

Ziyou goes on to suffer depression.

The show regularly references children’s mental health. However, the message is undercut by commercials advertising extracurricular classes throughout the series.

Adults say they feel trapped.

The feeling is illustrated by the CEO of a big company in the series, who says, “This is the worry for our generation: Our children may not be able to get into the same schools we went to. When they grow up, their salaries, social standing and jobs might not be as good as ours. If that happens, I won’t be able to accept it.”

Even the more relaxed parents, like Wan, can’t resist the pressure entirely.

While her eldest daughter does not take any, she still sends her youngest to extra English and math courses.

Additional research by Charles Zhang.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.