How essential child care providers are often stretched thin

How essential child care providers are often stretched thin

This interview is part of our series Econ Extra Credit with David Brancaccio: Documentary Studies, a conversation about the economics lessons we can learn from documentary films. We’re watching and discussing a new documentary each month. To watch along with us, sign up for our newsletter.

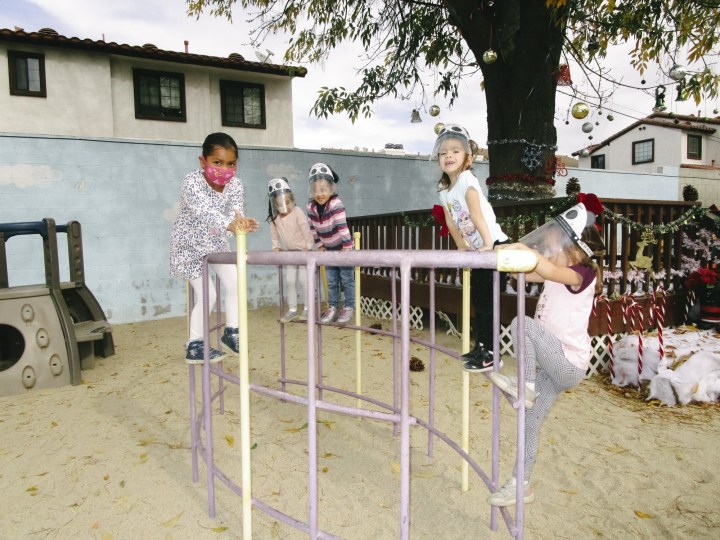

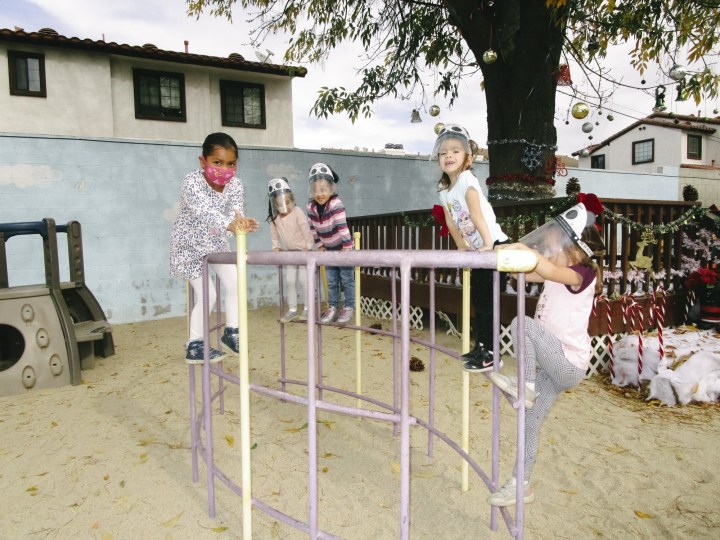

The documentary film “Through the Night” examines how child care providers Dolares and Patrick Hogan’s struggle to provide as much support as possible to the children they care for while not increasing the cost on the working parents who are often doing multiple jobs or overnight shifts to support their families.

It’s a situation that is not unique to the Hogans – child care workers, providers and early educators often find themselves stretched thin, according to early childhood reporter for KPCC and LAist, Mariana Dale.

“Early educators around the country hold some of the lowest paid jobs, the national median salary is $11.65 an hour,” Dale told Marketplace Morning Report host David Brancaccio in an interview.

“And when families need care that they can’t pay for, it’s really hard for them to say no, and that has consequences,” Dale said.

In California, that has translated to a shrinking supply of child care providers and increased burdens on several others which are often small businesses, as highlighted in Dale’s recent project, “Childcare Unfiltered.”

For example, one child care provider in Lancaster told Dale’s team she’s putting off buying certain services or items she needs in order to keep providing necessities for the kids she looks after.

“She needs hearing aids, but she cannot front the money to afford them … they’re not putting in money to their retirement savings, or being able to pay for critical health care,” Dale said.

Below is an edited transcript of David Brancaccio’s conversation with Dale on the state of the child care sector and how the COVID pandemic made things more difficult for those providers.

David Brancaccio: When you see how close to the bone the finances are of many child care facilities, it’s almost as if these are less businesses and more, I don’t know, labors of love. I mean, you’ve run into providers who pay out of their own pocket to make sure their children clients are getting what they need?

Mariana Dale: Oh, absolutely. And early educators around the country hold some of the lowest paid jobs, the national median salary is $11.65 an hour. And so this means when families need stuff like diapers, they need food to take home, I’ve talked to providers who are going out to Target and spending their own money to provide this for families, they are taking food out of their own pantries to feed these families. And when families need care that they can’t pay for, it’s really hard for them to say no, and that has consequences. I talked to a provider in Lancaster who knows that she needs hearing aids, but she cannot front the money to afford them. They’re not putting in money to their retirement savings, or being able to pay for critical health care. And they’re doing this because they know that the families they serve often can’t afford to pay any more than they already do.

Brancaccio: I mean, that last part is key to a lot of this. Economists might see child care as what they call, economists call, a failed market. The demand is there, right? People need it. The supply is limited. Normally in a market, that would mean the price rises, the child care facility would jack up prices. But child care centers are limited in what they can charge, right? Because how much can parents pay?

Dale: Right, child care is already one of the most expensive things that families pay for. And so sometimes I think when people hear about child care providers not being paid very much, they don’t really understand it, because they’re shelling out, you know, thousands of dollars for this care. And there’s a fundamental gap between the cost of high quality child care, and what any one source can really provide, whether that’s parents, you know, state or federal funding or even philanthropy.

Brancaccio: You know, one of the features of this film we’re watching this month, is you see how often the people running the child care center are cleaning surfaces. This was filmed before the pandemic; they’re swabbing down the desks, they’re cleaning the places where food is prepped, they’re swabbing down high chairs. You know, that stuff got pretty expensive during pandemic, didn’t it, the cleaning supplies?

Dale: Oh, absolutely. I heard multiple providers tell me about $20 cans of Lysol that they were having to buy to keep their facilities clean. And like you said, this is something they were already used to doing. But what changed is that the cost of all of this went up. And so even to provide the same standard of care they were already providing, it became quite a bit more expensive. And then on top of that, they were building plastic barriers to have in between kids. They were purchasing masks and protective equipment for their families and for their staff. And so these all added on top of the already expensive cost of providing child care, while at the same time, they were often able to serve fewer families either because of public health guidelines, or because of just dropping enrollment and concern from families. And so the business model of child care really fell apart.

Brancaccio: And this has been going on for a long time. But now here in the late summer of 2021, special case; surging demand for workers throughout the economy, people who had worked in child care might find work elsewhere for higher pay. That must represent a new hardship for people trying to keep these centers going?

Dale: Oh, absolutely. They cannot find the staff that they need to ensure that kids are well cared for, which means if parents come to them and need care, they’re having to turn parents away. But at the same time, I’m also hearing from providers who really want to be open, whose enrollment is still faltering, because parents are too hesitant to bring their children back, children who in many cases haven’t been able to be vaccinated, or their own finances are such that they can’t afford this care at this time.

Brancaccio: Now your work is in California, that’s been your focus. I think that state helps subsidize child care for some lower-income people. But that alone doesn’t seem to solve many of those challenges?

Dale: Oh, yes, even though there are subsidies available for very low-income families, not every family who qualifies is even able to access these services because the supply of child care has been dropping for years. In the last decade, we’ve lost more than a quarter of our family child care providers. These are women, often women of color who are providing childcare in their home. And for working families, they often provide the flexible hours that that folks need. And so without enough people to provide the care, you can have, you know, thousands of subsidies that go unused, even though there might be money there to help people access slots, but if the slots don’t exist, you’re kind of at an impasse.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.