Is there still dark money in Montana politics?

Although “Dark Money” was filmed less than 10 years ago, its depiction of politics almost seems quaint, bringing the viewer back to a time when politicians and special interest groups kept physical boxes of files and distributed issue-based advertisements via snail mail. In 2022, the reason dark money is used – to gain influence – is the same, but the mechanisms by which to exert that influence have changed.

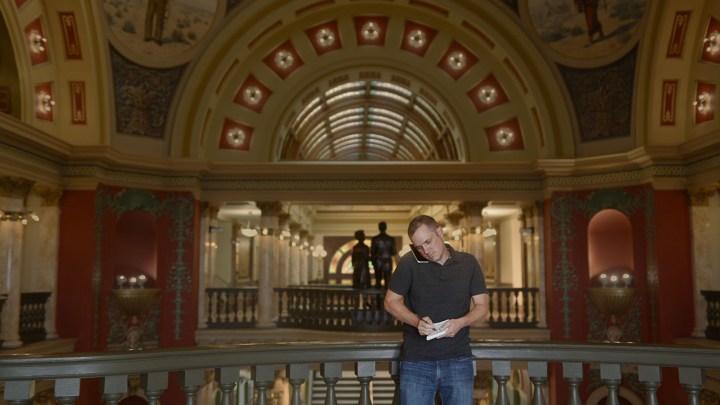

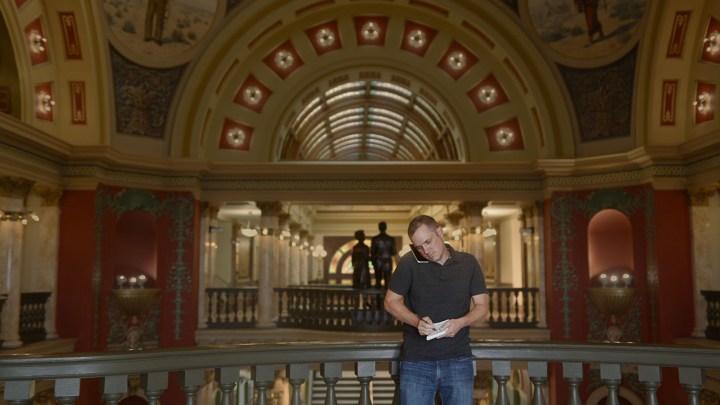

We talked to John Adams, the editor in chief of the Montana Free Press, to discuss what happened after the cameras stopped filming. Could dark money still be influencing politics in his home state?

This interview has been edited.

What was it like to help make this documentary?

John Adams: [Director Kimberly Reed] first reached out to me as a source to talk about my reporting, to share sources, documents. As a print journalist who’s perfectly comfortable having my byline be the most public-facing part of my life, I was content with that.

But when I lost my job at the Great Falls Tribune, which was the Gannett-owned daily newspaper that I worked for at the time, I think Kim realized that the decline in statehouse media was part of the story. At a time when there was an increase of unaccountable, untraceable corporate spending in elections, the watchdogs who would try to get to the bottom of these attempts to influence our politics were disappearing.

Kim made the decision to turn the camera on me as a subject rather than as a source, and I trusted her. I believed that she was in pursuit of an important story, and she had convinced me that I could be a vehicle to help tell that story.

What happened after the documentary premiered in 2018?

When people would ask me, “How do you start a successful nonprofit journalism organization?” I used to — jokingly — say, “Find yourself a documentary director and get yourself into Sundance.”

There are no ifs, ands or buts about it, the attention that “Dark Money” brought to what I was trying to do with Montana Free Press was game changing.

We launched Montana Free Press without any money or any idea how we were going to pay for it. By 2019, I had about $65,000 in the bank, which to me was enough to go ahead and pull the trigger on hiring some reporters. And once we were able to start producing content on a regular basis and showing people that we weren’t just “John Adams with a website,” we were able to generate more and more reader revenue, grow our audience, attract additional funders.

And it’s really exciting, because a lot more people understand how important nonprofit journalism is. Readers get it. Nonprofit institutions that fund things like journalism are coming around now in much larger numbers.

With disclosure laws in place, is there still dark money in Montana politics?

The short answer is we don’t know.

What we documented in “Dark Money” was kind of the old-fashioned version of dark money. Everything was analog, it was all in documents, spreadsheets, PowerPoint presentations. And a lot of it was done by hand. But the world has moved rapidly towards digitization.

One of the scary things is we’ve got all these digital platforms now that have various ways of microtargeting their audiences and selling opportunities for microtargeting. A political campaign or dark money group or a foreign government, for that matter, can say, “I want to target everybody who fits this demographic of likely voters,” and then they present an ad to just those people. And there’s no reporting requirements at the state or federal level.

So in some respects, you might argue that campaigns are a little bit cleaner, but with the rise of digital technology, microtargeting and the lack of government oversight or disclosure requirements for digital ads, I mean, we’re really in uncharted waters there.

We don’t know if disinformation sites are just people with their own political agenda who are volunteering to write their own opinions, or if they’re being funded by organizations that are looking to disrupt their political system.

There’s a scene in the film where the outgoing Federal Election Commission chair says that it could be foreign money being used to influence elections. There are a lot of countries that would like to point at the U.S. and say, “See, democracy doesn’t work.” One way to do that is through our political system and to cause chaos and disruption and do it, essentially, anonymously.

And the internet makes it cheaper to exert that kind of influence?

Yes, and easy. I think it would be so easy, with a little bit of money and the right amount of sophistication, to create all kinds of false narratives that take root and influence voter behavior in a local, in a hot-button local race. That’s my biggest concern, and that’s why I’m focusing less and less on the campaign finance laws and more and more on media literacy and education, and on how we rebuild trust in the information that we’re consuming online.

How do we build a strong news institution that people with broad political ideological beliefs can all agree that is a trusted news source, regardless of whether they voted for Trump or Biden?

I think that’s our path to getting out of this mess is rebuilding trust in community institutions and local journalism and statewide journalism, and eventually, God forbid, in national journalism.

Please let us know what “Dark Money” got you thinking about. Email your thoughts to extracredit@marketplace.org. We’ll feature some of those answers in an upcoming newsletter.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.