School lunches aren’t free to everyone anymore. Some advocates think they should be.

School lunches aren’t free to everyone anymore. Some advocates think they should be.

Abby Ratliff makes just a little too much for her kids to get free or reduced-price lunch at school. She and her husband looked at the application last fall, when their oldest was starting kindergarten, and didn’t qualify.

“Fortunately, we’re not at 200% of the poverty level, or whatever the cap is, but we’re really not that much over it,” she said.

Ratliff and her husband have three kids, 6, 3 and 19 months. She works as a nurse in Durham, North Carolina, and he used to work in sales.

“Once we had our second kid, however, it would have been the cost of three mortgages to have an infant and the at-the-time 3-year-old in daycare,” she said.

They looked at the numbers, and decided it made more sense for him to stay home with the kids. For the first couple of years, it felt pretty reasonable living on just her salary (which is “definitely less than six figures”).

“The past year it’s felt harder. The groceries have skyrocketed and, you know, gas prices are crazy,” she said. “Us two or three years ago living off of one income feels very different than us living off of one income now.”

So, when she and her husband discovered last fall that all kids could get free lunch at school, regardless of income, they were very excited.

Normally, the National School Lunch Program, like many other social benefit programs, is means-tested, or targeted — kids only qualify for free or reduced lunch if their family is at or below 185% of the poverty line, or if they go to a school in a low-income district that meets community eligibility criteria.

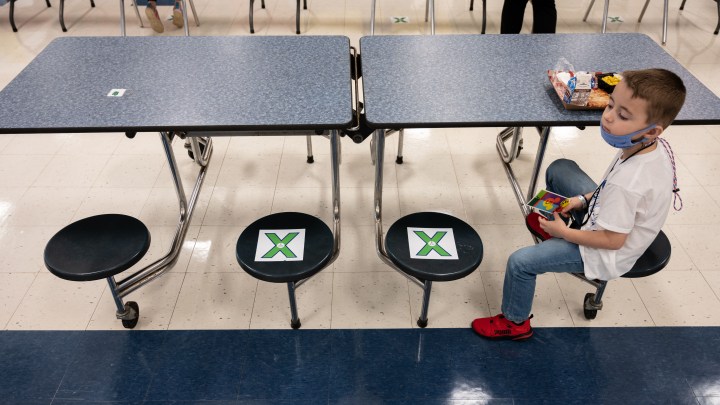

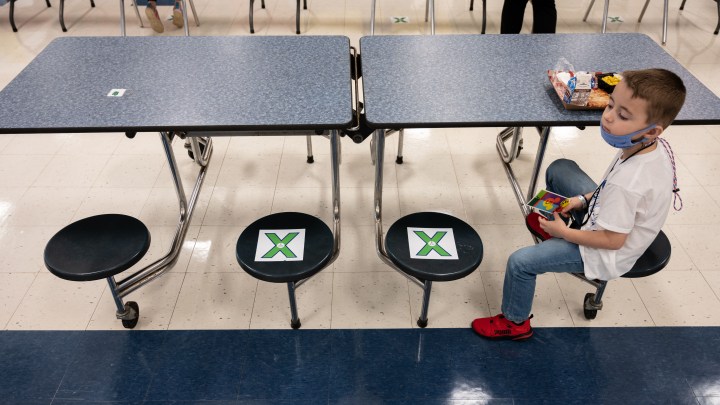

For the last two years, though, because of the pandemic, the federal government waived those income requirements and allowed schools to offer free lunch to all kids, regardless of income.

“It proved to be a really important tool,” said Elaine Waxman, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute. “We know typically that almost a third of food insecure households in the United States have incomes above that 185% cut off.”

Allowing schools to offer free meals to everyone helped keep a lot of kids from going hungry during the worst of the pandemic, Waxman said. “It’s also given us an eye into what, really, research was already telling us, which is that making meals universally available can bring a lot of benefits that people might not anticipate.”

Such as improving test scores, reducing discipline issues and decreasing stigma for low-income kids who do qualify for free lunch. It’s easier for schools too, because it means they don’t have to deal with all the paperwork and administrative costs of determining who’s eligible for free lunch and who’s not. It’s also easier for families.

“Some of the families you most want to reach through means-tested programs are the ones who are going to struggle the most to document income, resources or lack thereof,” said Indivar Dutta-Gupta, president and executive director of the nonprofit Center for Law and Social Policy.

That’s true of the National School Lunch Program and of other kinds of government benefits, like food stamps, SNAP or Medicaid.

“Sometimes, these means-tested or targeted programs can exclude the very families who you want to reach,” Dutta-Gupta said. Whereas programs that are universal, or nearly universal, do a better job of actually reaching the people who need them most.

“But you’ve got to recognize that it’s much more expensive to make programs universal,” said Bob Greenstein at the Brookings Institution.

“In Western Europe, more programs are universal. How do they do it? They raise a lot more in taxes.”

In the U.S., raising taxes is generally a non-starter. Given that reality, Greenstein said, “if you have a limited amount of resources, you can do far more to meet people in the most need by targeting the resources, rather than spreading them over everybody, all the way to the top of the income scale.”

Target a program too narrowly, however, and it likely won’t get a lot of political support; target it more broadly, and it will. Think Social Security and Medicare, last year’s temporary expansion of the child tax credit and universal free school lunch — all are very popular.

Even so, there is not currently enough support in Congress to make either the expanded child tax credit or universal free school lunch permanent. Lawmakers have allowed both to expire.

Dutta-Gupta at the Center for Law and Social Policy said that doesn’t mean they won’t come back … eventually.

“Historically, in the United States, structural improvements to social protection programs happen years after crises rather than during them,” he said.

For now, Abby Ratliff and her husband are trying to figure out how they’re going to make things work financially, come fall. Her husband is going back to school, which means they’re also going to have to start paying for daycare for their two youngest kids.

“So, with the ending of the free lunch program for all, that definitely added a stressor to us, going into next year,” she said.

They’re still doing OK, but they aren’t able to save much these days and they pretty much only spend money on necessities, now.

“We feel like we’ve already cut back a lot on what we can,” she said. “I mean, truly to the bare minimum, and changed what we buy at the grocery store.”

They’ve also planted a fruit and vegetable garden, which has helped them cut their grocery bill down even more. And they’ve made a spreadsheet of all the community food pantries and food banks nearby, just in case.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.