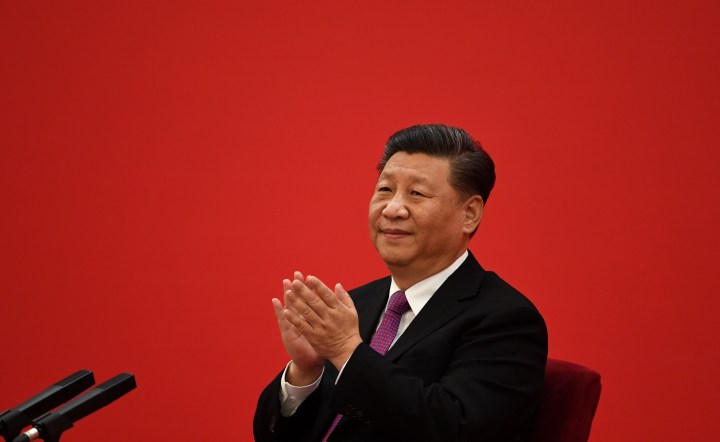

Inside Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ascent

In China, the ruling Communist Party is set to convene its 20th congress on Oct. 16. The largely ceremonial gathering is expected to include an extension of President Xi Jinping’s mandate for an additional five years.

Now nearing his 10th year in office, Xi’s meteoric rise to the top of China’s political system remains shrouded in mystery. But “The Prince,” a new, eight-part narrative podcast from The Economist, investigates the origins of the man who looks set to rule China for the foreseeable future.

“Xi Jinping is, perhaps apart from President Biden, the most powerful man in the world, and yet we know so little about him and about China, and it paints a portrait of a man who absolutely knows how to wield power,” Zanny Minton Beddoes, editor in chief of The Economist, told “Marketplace Morning Report” host David Brancaccio.

The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

David Brancaccio: Occasionally one sees reports here and there that COVID lockdowns or a slowing economy in China could put Xi Jinping’s leadership in question. But your team’s reporting finds this man remains on the ascendancy.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Absolutely. I think when the party congress convenes for its five-yearly gathering on October 16, it’s pretty certain that Xi Jinping will be reappointed as party leader, and he is going to be there for a while. People suspect possibly even for life, if he wants it. But our sense — there have been rumors about coups, all manner of things that hit social media very briefly — but my team’s sense is that he is very much in charge.

Brancaccio: You’re gonna start equating him with Mao Zedong here, right?

Minton Beddoes: Well, he’s very different to Mao. I mean, one thing that is interesting, the more you learn about him, is what he learned from that era. As you know, we’ve just launched this podcast called “The Prince,” which is an eight-part narrative podcast that really delves into Xi Jinping’s life, his rise and how he wields power. And I’m not a Sino expert, but I was absolutely gripped by his story. And what I hadn’t realized is quite how much he was influenced by his early life. His family, his father, was purged by Mao. His own life was very disruptive. He was sent away to the country[side]. It was a very turbulent and traumatic time for young Xi Jinping. But what he learned from that was the importance of the power of the party. He became, as some say, redder than red. He absolutely understood that, above all, you needed to keep the party in control. And that was, in his view, the way that you kept stability in China. And it’s really fascinating to see how he has absolutely reasserted party control, and of course, his own stamp on the party. And it’s striking, David, you know, I was thinking about it. Xi Jinping is, you know, perhaps apart from President [Joe] Biden, you know, the most powerful man in the world, and yet we know so little about him and about China, and it paints a portrait of a man who absolutely knows how to wield power. That’s why we called it “The Prince” with a direct reference, of course, to Machiavelli.

Brancaccio: Yeah, “The Prince” with that direct reference to Machiavelli. Now, President Xi was once seen as a reformer. But it is hard to square that with a man who’s aggressively purging rivals, going after ethnic minorities and ramping up the focus on political ideology there.

Minton Beddoes: It is. He was thought of as likely to be a reformer when he first came into this position. And I think it’s interesting to reflect on why everyone thought that. And one reason, I think, is perhaps because of his father. So he was a princeling. His father was, as I said, purged by Mao, but then rehabilitated under Deng [Xiaoping], and under Deng seemed to be a reformer. So people thought, you know, “Like father, like son.” And also because President Xi was relatively little known. He’d given very few press conferences, the parts of the country he’d been in were really not the sort of absolute centers of power. And so people thought, I think, because of his heritage and because they didn’t know very much about him, that he was likely to be a reformer. And you’re absolutely right, that’s turned out to be completely wrong. He has been absolutely single-minded about reasserting the party’s power. The party is now completely central in Chinese life. And he’s very clear, and he says it: East, west, south, north — the party leads everything. That is one of the many Xi Jinping mantras. For him, the party’s centrality in Chinese life can’t be overstated, and he sees himself very much at the apex of this party.

Brancaccio: Zanny, I do want to ask you about China and the world. Let’s start with its relationship with Russia. There have been some barbed comments directed at Vladimir Putin’s mess in Ukraine in recent weeks. Do you see the mutual admiration society, Russia and China, weakening some?

Minton Beddoes: Well, I think it’s worth remembering when the mutual admiration society, as you put it, sort of went up a notch, which was just before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. And I think there is now, seven months on, a sense of concern about what Putin is doing, the recklessness of what Putin is doing. But at the same time, you know, in Xi Jinping’s worldview, Russia is important because it is standing up to and pushing against the Western world order. And I think you need to put this friendship into that context. For China, and for Xi Jinping in particular, the world order that we’ve lived with really since 1945, which he sees as one being set by the United States with its focus on individual rights and so forth, as being, you know, fundamentally the wrong one. President Xi likes the idea of challenging the Western order. That’s why the notion of friendship between Russia and China built up. But the way the war has gone in the last seven months can’t have been something that he takes kindly to. So I suspect he is concerned about what Putin is doing and concerned about the consequences right now.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.