When did movie credits get so long?

This is just one of the stories from our “I’ve Always Wondered” series, where we tackle all of your questions about the world of business, no matter how big or small. Ever wondered if recycling is worth it? Or how store brands stack up against name brands? Check out more from the series here.

Listener Michelle Vadeboncoeur from Scarborough, Maine, asks:

When and why did movies change their credits sequences? If you watch older movies (particularly under the old studio system), top billing was listed at the beginning of the movie, and when the story is over there’s a big “The End” type title card and the movie is over. Current movies have some opening credits, but at the end of the story there’s 5-10 minutes of credits in tiny print listing everyone that may have even remotely touched someone involved in the movie’s production. I’m all for giving credit for work done, but that’s a lot of added film and titles services when movies didn’t need to do it before — so what pushed the change?

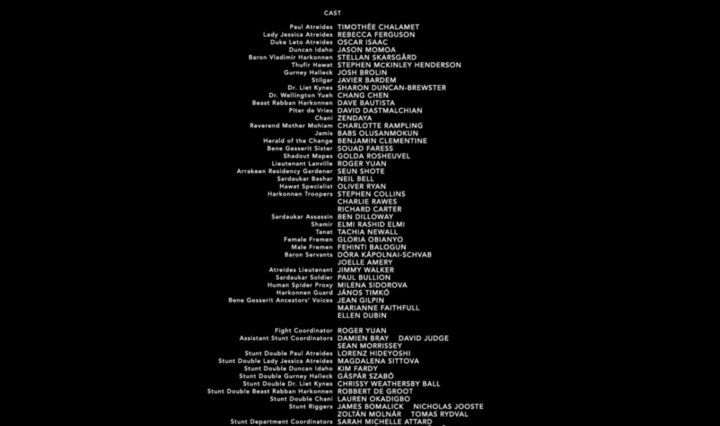

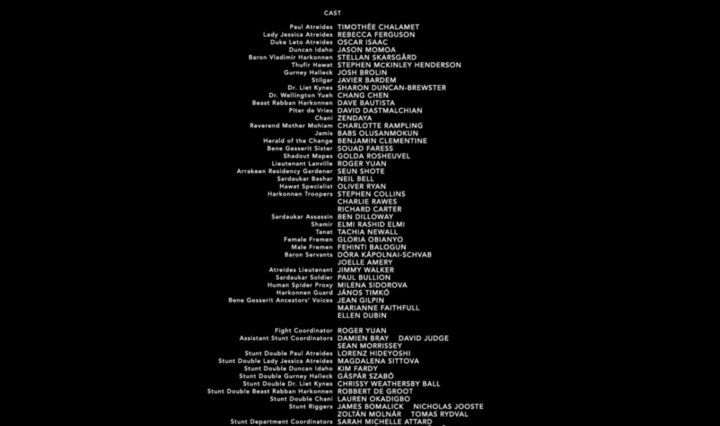

Credit sequences can last several minutes, including directors, actors, camera assistants and boom operators.

Vadeboncoeur remembers working as a licensed film projectionist back in college, and discovering that the 1996 film “Independence Day” had such a long credit sequence (almost 9 minutes) that the credits had their own shipping reel of film.

But in Hollywood’s early days, credits weren’t even listed.

Rising labor power and a desire from the audience to find who certain stars and crew are have led to the growing size of on-screen credits throughout film’s history.

Credits are crucial in Hollywood, because they allow workers the ability to build on their previous credits and get new work, said Kate Fortmueller, an assistant professor of entertainment and media studies at the University of Georgia.

“Credit is a way to gain power within the capitalist media system. So any kind of gain, or any kind of larger credit, has to do with how well you or someone else negotiated for you,” Fortmueller said.

So it’s not just about fame. It’s about setting yourself up for future bargaining and establishing your value, Fortmueller said.

The rise of fandom

The very earliest films actually didn’t have credits, merely listing the title of the film at the beginning of the movie, according to Shelley Stamp, a film and digital media professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

“Some of the most high-profile production companies would include their logo in individual shots as a way to kind of brand their films and prevent piracy. But cast and crew were initially not identified at all,” she said.

That changed in the 1910s with the rise of fan culture.

“People wanted to know the names of the stars they were seeing,” Stamp said.

Florence Lawrence and Florence Turner were some of the earliest examples of actresses whose fans clamored for details on, Stamp said. She noted that they were initially known by the company they worked for. So because Lawrence worked for the Biograph Company, she was known as “the Biograph Girl.”

“Fans started writing into fan magazines saying, ‘Who is this Biograph girl? Tell me more about her,’” Stamp said.

By the 1910s, Stamp said some of the silent films during this period let the audience know who was playing the main characters, in little vignettes where the star would then look directly at the camera, like the 1915 film “The Cheat.”

Credits throughout the 20th century

Doron F. Eghbali, senior partner at the Law Advocate Group, said that credits grew as Hollywood guilds became more prominent and more powerful. He said on-screen credits are determined by producers, along with contracts in place with unions.

From the 1920s to the 1960s, many films include opening credits, which might show the movie title card, the main actors, director, screenwriter, director of photography and other major players involved in the film. A simple “The End” appears at the end of many of these films in the 1930s and 1940s.

However, there were no uniform rules. In upcoming decades, some films, like 1950’s “All About Eve,” have an extensive list of closing credits while 1963’s “Cleopatra” merely has a “The End” card and the name of the production company.

Later on in the 1960s, releases such as “Romeo and Juliet,” “2001: A Space Odyssey,” and “The Dirty Dozen” also have a significant list of ending credits (although they’re nowhere near as vast as current films).

Some films also began to feature more elaborate credit designs. “Films like Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Vertigo’ in 1958, or virtually any of the James Bond films in the ‘60s and ‘70s have extraordinary opening credits sequences that are very engaging and dynamic and not part of the film’s narrative world itself,” Stamp said.

In the 1970s, closing credits started to run several minutes, according to David Bordwell’s book “The Way Hollywood Tells It.”

Most workers were under contract during the studio era, and thus didn’t receive billing. But as film moved toward “the package-unit system of independent production,” workers were freelancers and needed that public credit, Bordwell wrote.

Compared to the days of Hollywood where studios were responsible for the production of films, package-unit systems mean the producers organize a film project, according to Beverly Boy Productions.

By the 1980s, there’s a clear distinction between opening credits — listing just major cast members and creative key personnel — and closing credits where there’s an extensive list of the people who worked on the film, Stamp said.

Over the past decade or so, more filmmakers and studios have also been enticing viewers to stay with bonuses, like the alternate ending included in “28 Days Later” or how Marvel films include teasers for upcoming installments, Stamp said.

The benefits of longer credits

Fortmueller is in favor of longer credit sequences, pointing out that in the past, costume design credits were typically just granted to the department head.

“The reality is, they weren’t doing all that work,” Fortmueller said. “I think that what you lose when you only have one person in these credits is you don’t really have a sense of who that department labor is. So it’s a way that you might be erasing some of the contributions of women who are doing really active creative work within these departments.”

Fortmueller encourages audiences to watch beyond the end of the film and read credits, so that they can recognize the labor that went into the movie.

“It takes a lot more people than the director and the star,” she said.

Stamp said she thinks longer credits are a positive development because it gives credit to people who worked on the production. But while more people than ever are now getting credit, there’s a technological conundrum happening with the rise of streaming. Stamp pointed out that these services autoplay the next show or movie, leaving people like her frustrated and trying to scramble to figure out how to continue watching them.

Longer credits are a function of the increased amount of labor involved in a film. “An effects-driven movie is always going to have really long credits at the end of the movie because there are so many people that worked on [it],” Fortmueller said.

But Fortmueller added another reason why certain people have gotten credit has to do with how well they were able to articulate their value. The importance of certain roles seem clear to us now — films are visual, so of course a cinematographer would be crucial.

But this logic hasn’t always been obvious.

Fortmueller said the issues surrounding who gets credit, who gets to be named, is in some ways a labor battle.

“If people know who you are, if you’ve established yourself within your career, you can negotiate for more money. And if the studio can make you anonymous, then you’re replaceable,” Fortmueller said.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.