“The Netflix Model” for antibiotics

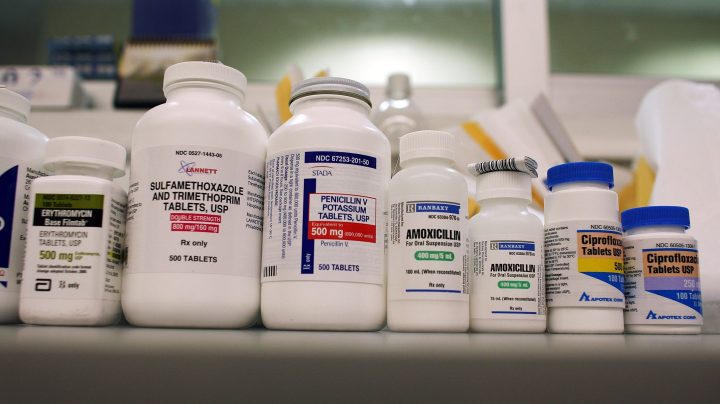

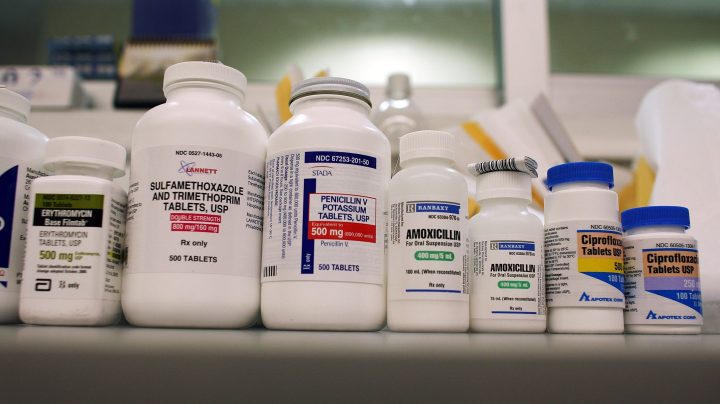

Microbes are developing resistance to antibiotics, and the free market isn’t keeping up. Most big antibiotic producers have left the market, the rate of new antibiotic commercialization is painfully slow, and the pipeline for new antibiotics for high-priority pathogens is “insufficient,” according to the World Health Organization.

The economics of antibiotic production are broken: Prices are low, sales for novel antibiotics are low by design to avoid overuse, and markets are fragmented. Large pharmaceutical firms have left the field. New players face rough economics, some have gone bankrupt, and investors have largely walked away.

There are proposed solutions. One has earned a catchy nickname: “the Netflix model.”

“The analogy with Netflix is good because in some months you may binge on a whole bunch of episodes. Whereas in other times, you know, it’s in summer, you’re outside, you don’t watch anything, but you still pay your subscription,” said James Anderson, executive director of global health at the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations and chair of the AMR Industry alliance.

The same principle is being proposed to surmount some of the problems ailing the antibiotic market: prices that are too low to attract investment, and growth opportunities that are limited in a market made small by design. Antibiotics — and novel antibiotics in particular — should not be consumed willy-nilly, but instead used as little as possible as weapons of last resort.

“The ideal state is to have very low volume use, and therefore, it’s a market failure because a lot of companies can’t recoup their investment once they’ve made a new medicine,” said Jocelyn Ulrich, deputy vice president of innovation policy at PhRMA, a pharmaceutical industry trade group

So one idea — the Netflix model — is to have governments pay pharmaceutical companies a negotiated amount to provide a new antibiotic whether it’s used much or not.

“So then the manufacturer would know they would have a guaranteed amount of revenue and, in exchange, they would manufacture enough of the medicine to cover all the need in the government programs,” said Ulrich.

Congress has been considering a version of this for several years in the Pasteur Act. Antibiotic producers would still be able to sell to the private sector as well, at market rates. Should private sector sales reach a certain threshold, government payments would stop.

Pharmaceutical companies would still be taking on risks. There’s no guarantee an antibiotic will be approved by the FDA. But one question is calculating how much the pharmaceutical company should get.

“That is a very complicated exercise,” Anderson said. He estimates a company might need a “ballpark figure” of $2 billion to $4 billion total for each antibiotic to attract investment into the sector. U.S. legislation would offer $750 million to $3 billion to supply Medicare and Medicaid.

A version of this is already underway in the United Kingdom for two new antibiotics.

“Instead of looking at the value of two trial drugs to the individual patient, we looked at clinical criteria to meet unmet need and novelty and impact on the patient, the impact of not passing it on to the ward and community,” said Dame Sally Davies, a physician and the U.K. special envoy for antimicrobial resistance.

“We looked at non-critical criteria — security of supply, making sure they’re properly used, and cost, and we estimated the value to England’s national health service over 20 years and assigned each of the drugs a value for a 10-year contract,” she said.

Shionogi and Pfizer are set to receive a combined £10 million a year for the drugs to supply the U.K.’s National Health Service.

There are other examples, too. The state of Alabama is trying out a subscription model to fight Hepatitis C. Another idea — proposed in Europe — is to offer companies that make antibiotics valuable and flexible vouchers to extend patents. Those vouchers could be used by the company producing the antibiotic or sold to another company to use on another drug. (The longer the patent, the more money a pharmaceutical company can make.)

“So the value goes to the company that made the antibiotic, not through selling more of the antibiotic or having a high price, but through this voucher,” Anderson said.

Novel contracts and incentives like this may not be sufficient, according to Dr. Evan Loh, CEO of Paratek Pharmaceuticals, which sells a new antibiotic called Nuzyra. Its antibiotic has been in development since the ’90s and cost over $1 billion. And some hospitals are resistant to paying for newer and more expensive antibiotics, he added.

“Let’s say an antibiotic costs $400 a day versus an older, less effective antibiotic for $10 a day. Where’s their choice? We’ve run into hospitals today that say, ‘We’re not using any branded antibiotics, period,'” he said. “So there’s no way we can even get on the formulary for doctors to have a choice to use our product.”

Part of the issue, Loh said, is the way many hospitals are reimbursed for hospital visits. It’s in a lump sum that covers everything, including x-rays and antibiotics.

“When hospitals look to make their margin or even some profit, they see low-hanging fruit such as an antibiotic,” he said.

Loh calls the antibiotics market “fragile and broken.”

Bugs, of course, don’t have economic considerations about markets and investment returns. Bugs just replicate and evolve — whether humans take notice or not.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.