Inside the push to limit China’s access to advanced chip-making tech

Inside the push to limit China’s access to advanced chip-making tech

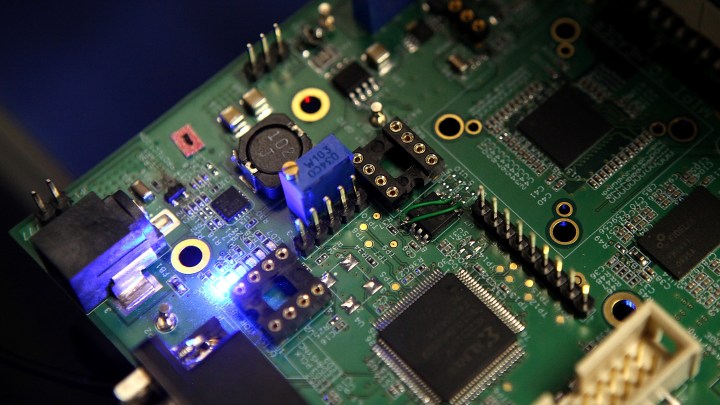

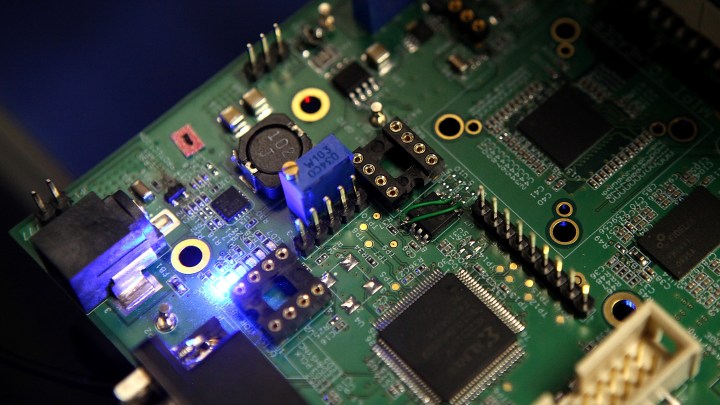

The United States has persuaded the Netherlands and Japan to restrict exports of high-tech chip-making equipment to China.

Along with the U.S., the Netherlands and Japan are home to some of the most important companies that produce the equipment needed to make advanced semiconductors. This effort to control exports, kicked off by the Biden administration last October, takes direct aim at China’s capacity to make the best microchips.

Marketplace’s Sabri Ben-Achour spoke with Chris Miller, a professor of history at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, about what’s behind this move.

“The reality is that history shows whenever powerful countries have access to advanced computing capabilities, they deploy this for intelligence and military uses,” said Miller, who is also author of “Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology.”

The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Sabri Ben-Achour: So I think we need to start with explaining the “why.” Why any of this? Why is the U.S. so intent on blocking China from accessing high-end computer chips?

Chris Miller: Well, high-end computer chips of the type that are controlled by the U.S. regulations are used in advanced data centers where AI systems are trained. And today, there’s just a small number of countries that basically control the supply chain for producing these chips. And that’s why the U.S. is trying to restrict access to the types of tools you need to make these chips from being sent to China.

Ben-Achour: Is this a national security issue? Or is this really an economic competition issue and a desire to sort of maintain economic prosperity?

Miller: No, this is completely about national security concerns. The reality is that history shows whenever powerful countries have access to advanced computing capabilities, they deploy this for intelligence and military uses. Whether it’s some of the first computers that were deployed by the British during World War II, to crack Nazi codes, or whether it’s the U.S. use of supercomputers during the Cold War to track Soviet submarines. In the Cold War, the KGB and Soviet Union and the National Security Agency in the U.S. had privileged access to their country’s most advanced computers for signals intelligence purposes. And today, there is no doubt that all of the world’s key powers are thinking harder than ever about how to apply artificial intelligence to espionage, to signals intelligence and to military systems. And that’s exactly what these controls are trying to target.

Ben-Achour: The U.S. had to fight kind of hard to get other countries on board with its sanctions against Huawei, for example. Was it a hard sell to get Japan and the Netherlands to join the U.S. on restricting chip exports?

Miller: I don’t think it was that hard of a sell given that a deal was struck relatively quickly. And I think actually, if you look at debate in the Netherlands, as well as in Japan, what you find is that there’s been a real shift in views about China, as well as a shift in views about the military and security applications of artificial intelligence and advanced computing.

Ben-Achour: The Wall Street Journal reported that China’s top institute for nuclear weapons research has been buying and using high-end U.S. computer chips that were supposedly restricted from going to China all the way back in 1997. So how effective do you think this round of exclusion is going to be?

Miller: Previously it was illegal to send U.S. chips to military uses in China, but legal to sell them to companies that said they were going to use them for civilian purposes. But the reality is that the same types of chips that can train a car to drive semi-autonomously, can also train a military drone to fly semi-autonomously. And there were plenty of well documented, open source reporting about ways that ostensibly civilian uses were actually helping the Chinese military. And so the new U.S. regulation prohibits any advanced chips of this type to be sent to China.

Ben-Achour: Do you think China could get around this somehow? Get those chips elsewhere?

Miller: Well, they’re going to try but I think it’ll be difficult for a couple of reasons. First off, the chips are produced by one company, in one factory in Taiwan. And because the distribution networks for this particular type of chip are relatively narrow and trackable, I think the U.S. has a reasonable case to make that it’s going to do a pretty good job of limiting China’s access to this type of chip.

Ben-Achour: Can it not start developing its own high-end chips? How far away do you think we are from that?

Miller: The reality is that today, all of the most advanced chip making facilities in China, only work because they’re able to import tools from abroad from the U.S., from Japan and from the Netherlands. And right now, there simply aren’t credible domestic competitors in China for these tools from foreign companies. So China’s certainly gonna spend more money trying to build up a chip industry, but it’s got a really difficult pathway ahead because right now it’s years behind, when it comes to manufacturing the machine tools that are needed to make chips.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.