Why does the U.S. still use calories on nutrition labels instead of kilojoules?

Share Now on:

Why does the U.S. still use calories on nutrition labels instead of kilojoules?

This is just one of the stories from our “I’ve Always Wondered” series, where we tackle all of your questions about the world of business, no matter how big or small. Ever wondered if recycling is worth it? Or how store brands stack up against name brands? Check out more from the series here.

Listener and reader Spencer Kitchen from Ogden, Utah, asks:

I think I read somewhere that the joule replaced the calorie. That has led me to wonder: Why do we use outdated units (in the case of calories) in the U.S., or even the metric system at all, on consumer labeling?

The calorie — a unit of energy with a very technical definition that is now used by people to assess how much food they should be eating — has been a part of our vernacular for more than a century.

Even before nutrition labels had become mandatory on packaged food, the term had persisted for decades in diet books, textbooks and cookbooks.

The U.S. has embraced its use on food labels, despite the adoption of the kilojoule by other nations as well as criticisms it’s received over the years (opponents dubbed the calorie a “foolish food science” back in the early 20th century, while contemporary concerns criticize the practice of calorie counting).

Countries such as Australia and France use the kilojoule, a metric unit, on their food packaging to express a food’s energy content. One calorie is equivalent to 4.184 kilojoules (while 1 kilojoule is equivalent to 1,000 joules).

Dara Ford, a professorial lecturer of health studies at American University, said she thinks we still use the calorie because of historical precedent, despite our use of the metric system on other parts of the nutrition label.

“We are used to the calorie and its calculation does predate the joule and the kilojoule,” she said. “It’s one of the most well-recognized tools from a nutrition-education perspective.”

Why we still use the calorie: a British vs. French rivalry

A calorie is technically the amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of 1 gram of water by 1 degree Celsius, and might be used in chemistry or physics research.

But these calories are too small to measure food, health experts say, so companies technically use big Calories — with a capital C — on nutrition labels. This big Calorie, which is interchangeable with a kilocalorie, is equivalent to 1,000 small calories, and is the amount needed to raise 1 kilogram, or 1 liter, of water by 1 degree Celsius. An item that has 200 big Calories actually has 200,000 small calories.

Many of us aren’t aware of this distinction, and when we discuss calories, as we are in this piece, we’re actually referring to big Calories.

The calorie we’re familiar with started to enter American vocabulary in the late 19th century, according to James Hargrove, an associate professor emeritus of food and nutrition.

The American chemist Wilbur Olin Atwater, who is considered a pioneer in nutrition studies, described the calorie to American audiences in a magazine called “Century” back in 1887.

Hargrove wrote that Wilbur chose this as an energy unit for food because “the Calorie was the only named energy unit that existed in English dictionaries of the time.” Although the joule was “proposed as an electrical unit in 1882,” it had not yet entered our lexicon. The term “Calorie” was also included in an 1894 issue of Farmers’ Bulletin, a publication from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Calories ended up being used as the unit of USDA food energy content in tables that Atwater developed at the end of the 19th century, Hargrove explained to Marketplace over email.

As it turns out, even a calorie has an economic function. “In the old days, people were plowing fields behind horses, and knowing how much food was needed to do that work by the man and the farm animal was very important to the farm economy,” Harnack said.

Hargrove, in one paper, wrote that Americans were interested in managing their weight back in the day, as they still are, and the calorie was also included in articles and books, including the best-selling book “Diet and Health with Key to the Calories” from 1918.

But not everyone was on board with this unit of measure, with the British advocating for the joule, named after James Prescott Joule, starting around the 1880s. “The Calorie was a ‘French’ unit, and the British argued that it was imprecise,” Hargrove said over email.

The British won out decades later. The International System of Units (SI), also known as the modern metric system, was launched in 1960 and had adopted the joule.

“European advisory committees used that unit for their food labels, and the Calorie was abolished,” Hargrove said.

Why prioritize the joule or kilojoule over the calorie? Well, there are several base units included in the International System of Units (SI), also known as the metric system. A joule is derived from other units within the metric system, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (A joule equals 1 newton of force over a distance of 1 meter).

“The calorie cannot be derived directly from the basic SI units without using an experimentally determined factor, whereas the joule corresponds with the energy measurements in all branches of science on which the nutritional sciences depend,” explained FAO.

Hargrove also noted that a joule can be calculated based on electrical currents, which physicists preferred, while determining the amount of heat needed to raise a liter of water by 1 degree Celsius can vary based on elevation and room air temperature.

But the U.S. ended up remaining loyal to the calorie. “People had known about the Calorie as a unit of food energy (measured as heat) since 1880, and there was no valid reason to confuse the public with a technical name (joule) that is only a man’s name,” Hargrove added.

Because consumers are so familiar with the calorie, Ford said she thinks transitioning to the metric equivalent, the kilojoule, would be “pretty disruptive.”

Lisa Harnack, a professor of epidemiology and community health at the University of Minnesota, said she thinks the lack of consistency with other countries may create confusion. However, she said it would be “a huge effort” to educate and help the public understand a new unit.

Whether a meal tells you that it has 500 calories or 2,000 kilojoules, consumers are really using these units to understand how they fit in relative to their diet, and the actual unit being used arguably may not matter.

“Most people do not know what a calorie, kilocalorie, or kilojoule actually measures in terms of raising the temperature of water, and how this translates to human metabolism,” said Ford of American University. “Because of that, they’re used more as a tool for monitoring intake.”

So why are there metric measurements on other parts of the label?

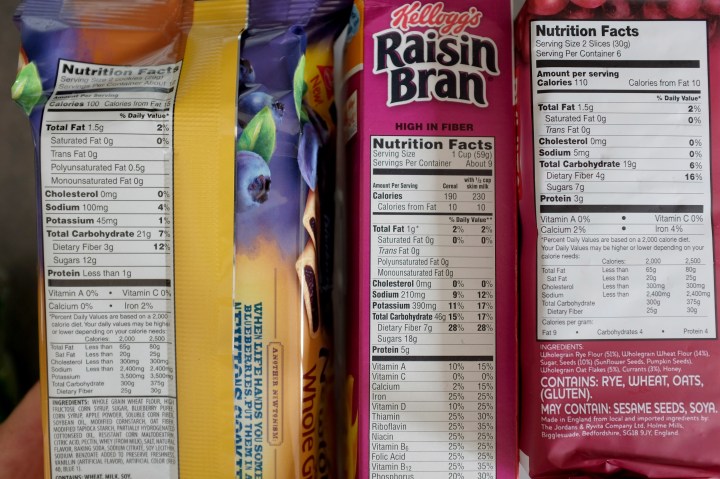

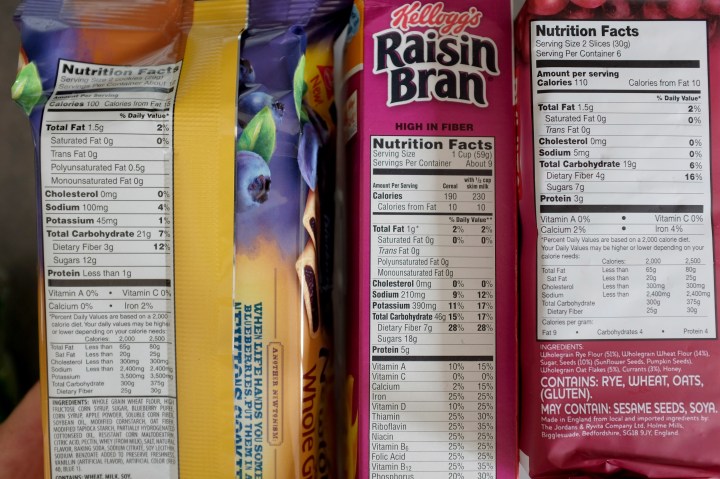

If you look at the food products we use, there’s a mishmash of information listed in both U.S. customary units and metric units. You’ll see canned goods listing nutrients like protein and carbohydrates in metric. But the net weight might be in both metric and customary.

“FDA — which regulates food labeling for packaged foods — has requirements that stipulate metric units be used for nutrients, in part to be consistent with the Metric Conversion Act of 1975 that was enacted to voluntarily increase use of the metric system,” Harnack explained.

The FDA had a very logical reason to do this: the customary units Americans were used to — such as ounces — are too large to describe something as small as a nutrient. For example, Ford pointed out it wouldn’t be useful to put an amount like 0.026 oz, which is where a metric unit like the gram comes in handy.

In the 1970s, soda companies also started to use metric units and were able to use their new sizes as a marketing tactic. Pepsi-Cola, which was competing with Coke and wanted to improve its bottle design, found out that households were always running out of Pepsi, Marketplace reported. That’s why the company ended up launching the 2-liter bottle.

7UP also released products in half-liter and liter sizes amid metric mania, even using a campaign slogan called “follow the liter,” and published a 60-page guide for teachers on the metric system.

Historian Stephen Mihm told Marketplace back in 2017 that metrification gained momentum because there were concerns about a decline in American exports. “That got chalked up, rightly or wrongly, to our intransigence about not adopting the metric system,” he said.

In the 1990s, the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act was amended to require that net contents of certain packages be expressed in not just customary units, but metric ones as well. For businesses that wanted to sell their products internationally, it was advisable to use metric units to stay competitive.

Despite America’s staunch adherence to the calorie and its individualistic tendencies, the country hasn’t been immune to the pressures of global competition. A product’s labeling doesn’t just tell us about the food we’re eating or operate solely based on practicality: it’s also a story about economics and our complicated, decades-long relationship with the metric system.

Reader questions may be edited for clarity.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.