Why Egypt’s Queen Nefertiti is one of the original beauty influencers

Why Egypt’s Queen Nefertiti is one of the original beauty influencers

The eyeliner industry might just have to thank Queen Nefertiti for turning the cosmetic into a worldwide sensation.

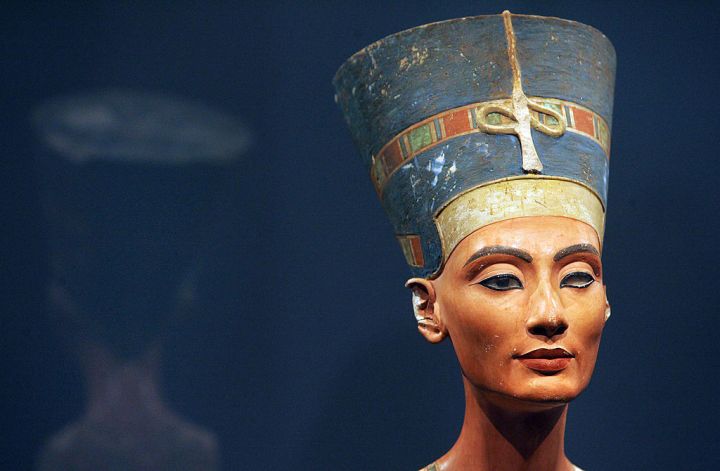

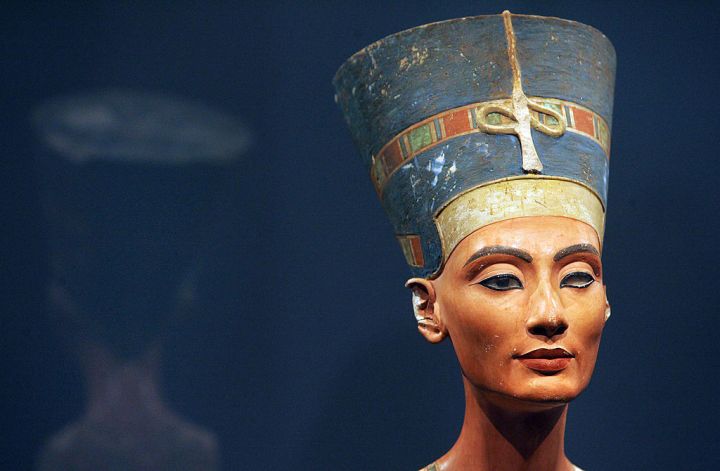

In her book, “Eyeliner: A Cultural History,” journalist Zahra Hankir looks at how the public unveiling of Queen Nefertiti’s bust in the 1920’s made a global splash — and popularized the use of eyeliner. “You would see hair salons in America have replicas of her bust in their windows. You would see fashion houses craft lines that were entirely inspired by Nefertiti,” said Hankir. ” And, of course, you had many women and also celebrities start to wear eyeliner.”

Nefertiti’s status as a fashion beauty icon continues to this day, and according to Hankir, she’s one of the first beauty influencers. “We’re talking about 100 years of infatuation with her looks,” she said. “You had Beyonce who, for example, paid homage to her in Coachella. Queen Latifah has made nods to her, Lauryn Hill has made nods to her.”

The following is an excerpt from Hankir’s book that looks at some of the reasons why Queen Nefertiti’s bust had such an impact when it was revealed to the public.

Before Nefertiti was propelled into the spotlight when her bust was officially unveiled to the public in 1924, Vogue had already taken an interest in ancient Egyptian fashion. “The art of makeup, too, is as old as Egypt and played an important part in the feminine toilette. Rouge, kohl, and a powdered green malachite which was used about the eyes were the chief cosmetics,” declared a 1921 feature exploring the era’s style. “From the Far East comes the true kohl so becoming to brunettes and, in a modified form, to blondes,” reads a November 1922 article.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 by British archaeologist Howard Carter affected Western popular culture in its own right, spurring what is commonly referred to as Tutmania or Egyptomania, a period of intense, Orientalist fascination with ancient Egypt in the West. When the pharaoh’s tomb was unearthed, its chambers offered insight into how the man lived and looked and how his wife, Ankhsenamun– the daughter of Nefertiti– did, too. The reveal sparked a publicity rush and an interest in kohl, the mysterious substance that seemingly possessed magical powers. Tutankhamum garnered more coverage than his partner, but she didn’t fall by the wayside– her lined eyes also caught the attention of Vogue in 1923.

In “The Kohl Pots of Egypt,” Dudley S. Corlett asks readers to join him in “softly” pulling back “the tapestry which hangs before the portal of Ankhsenamun’s bed-chamber” as the journalist unsettlingly imagines how she prepares for the day. First, he describes a queen with olive skin “stretching her supple body veiled in gossamer garments.” After taking a bath and putting on a saffron silk robe, Ankhsenamun heads to her vanity to pamper herself. Before tending to her hair, her kohl is the first and only cosmetic she wields. This item of makeup, Corlett writes, exercises its unabated wiles today, for, above the white veil of Moselem women, daring, kohl-rimmed eyes mock at men and keep them guessing at beauty hidden with discretion from their jealous gaze.” Corlett presents kohl and the women who wore it as “exotic” element of the orient that exist only to tease men, especially Western men. The looks of such women, he seemed to say, were untouchable– far away, in a remote land, and of a bygone, primitive era. (He also speaks of women’s sense of hygiene.)

With the display of Nefertiti’s bust in Germany, the world would come to know the queen herself and invite her into discussions about beauty, subsequently making way for kohl and eyeliner in their beauty kits. Borchardt’s miraculous find sparked a craze when it came not only to Egyptian artifacts but to “strange” looks in general– and how to gradually come to terms with or even achieve them. The subsequent focus on Nefertiti’s physical appearance, particularly her darkened eyes, had a ripple effect on modern beauty standards. In many ways, the sculpture would redefine and refine them. Finally, there was an undeniably beautiful rendering of the enigmatic Nefertiti upon which to fixate. Orientalist imagery such as the headscarf-wearing women, flying carpets, camels, and scoring Arabian deserts were partially eclipsed by a distant, yet somehow relatable, queen.

According to Egyptologist Chris Naughton, the queen’s eye makeup played a significant role in our perception of her beauty. “In some ways, it’s too good to be true,” he tells me. “You wouldn’t expect the Eighteenth Dynasty’s conception of what is to be a beautiful woman to be the same as ours, and yet she fits what we understand to be perfectly beautiful. She really was very good-looking, and kohl certainly helped.”

If ever there was an appropriate name, it was Nefertiti’s. With the discovery and display of the queens bust and her elegantly lined eyes, the Beautiful One had, indeed, arrived.

From EYELINER by Zahra Hankir, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Zahra Hankir.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.