Overdraft fees, long associated with big banks, are big business for credit unions too

Overdraft fees, long associated with big banks, are big business for credit unions too

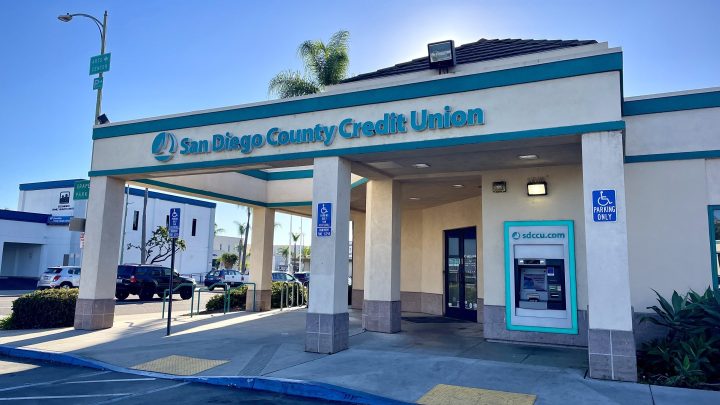

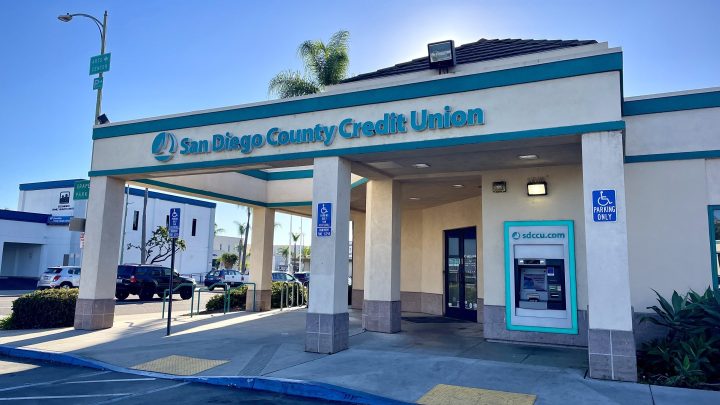

Curtis Fitzgerald has been a San Diego County Credit Union customer for years.

“I see the credit union, ideally, as a part of the fabric of the community,” he said.

But his feelings toward San Diego County Credit Union started to sour somewhat when his son Antonio began banking there. Antonio worked hard, according to Fitzgerald, but he always seemed to run out of money.

“He’s only 20, and he’s not a financial wizard, he would admit,” Fitzgerald said. “Finally, he came to me one day and he says, ‘What is this $32 fee?’”

It was an overdraft penalty. And a look at Antonio’s account statements revealed he’d paid a number of them.

Many people associate overdraft fees with large commercial banks. And that’s understandable — last year, big banks brought in nearly $8 billion in overdraft revenue. But, it turns out, the fees are big business for some credit unions too. A law passed last year in California is shining a light on how much these not-for-profit financial institutions are collecting from customers whose checking accounts go negative.

All told, credit unions chartered in California generated just over $250 million in overdraft revenue in 2022, according to data collected by the state.

Fitzgerald worked with his son on money management and talked about how to avoid overdrafts going forward. The credit union’s overdraft policy is accessible online, and Antonio could check his account balance at any time. Still, Fitzgerald felt the penalties were excessive.

“It seems like a credit union shouldn’t be charging someone $32 for a transaction that’s, you know, $10 or $20,” he said. “Four times a day, maybe even.”

It seemed to Fitzgerald more like something you’d expect from a big bank. And that was ironic, considering San Diego County Credit Union’s ads that lampoon greedy banks. In one commercial, when a customer asks a question, the banker only responds with one word: “Money, money, money.”

The commercial’s tagline hammers the message home: “We’re nothing like a big bank. We’re better.”

San Diego County Credit Union, which declined an interview request, collected $18 million in overdraft fees last year.

For years, big banks have had to disclose proceeds from overdrafts. But that’s not the case with credit unions, according to Aaron Klein, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

“Credit unions have largely escaped scrutiny on overdraft by a combination of wrapping themselves in the ‘good guy flag’ as a nonprofit, mission-oriented entity and by not releasing data to the public,” Klein said.

California’s new law is changing that. All state-chartered credit unions and banks are now required to disclose how much they generate in overdraft revenue on an annual basis.

Klein argues that overdraft fees disproportionately impact low-income customers and can make their financial situations worse.

“Regulators should treat overdraft as the five-alarm fire that is burning through low-income communities and families living paycheck to paycheck,” he said.

But some credit unions, which often tout their connection to the community, push back on this characterization. They frame overdraft coverage as a benefit for customers.

“We call it a service,” said Bill Birnie, CEO of Frontwave Credit Union, based in Oceanside, California. “We don’t call it a fee — it’s not a junk fee.”

He added that many of his customers rely on overdrafts at the end of the month as a kind of “bridge” before their next payday.

That said, Frontwave collected nearly $8 million in overdraft fees last year. Without that revenue, according to the credit union’s financial records, it could have lost money in 2022.

“So it is an important source of income to us,” he said. “I just don’t think we do it in a predatory way.”

Big banks have faced scalding criticism for their overdraft practices in recent years from politicians and the public. Now, overdraft revenue at big banks is down. Some initiated overdraft grace periods, while others eliminated the fees altogether.

Advocates hope the new law in California forces credit unions across the country to also open their books — and reevaluate how they enforce overdraft penalties.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.