“Sell, sell, sell”: How Neiman Marcus’ flagship store catered to the superrich

Share Now on:

“Sell, sell, sell”: How Neiman Marcus’ flagship store catered to the superrich

Do you have a holiday hangover from a gluttony of consumerism? Perhaps you are exchanging unwanted gifts or even taking a self-imposed spending hiatus? Other readers may be nabbing post-holiday deals and buying stuff with all those gift cards received from family and friends. Our January selection for Econ Extra Credit may or may not curb your appetite to consume, depending on what you make of the film.

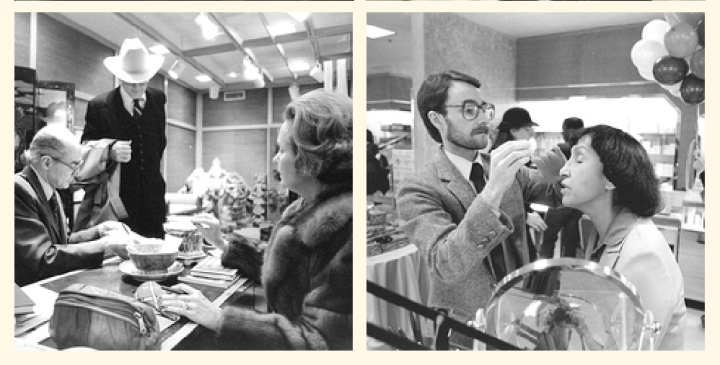

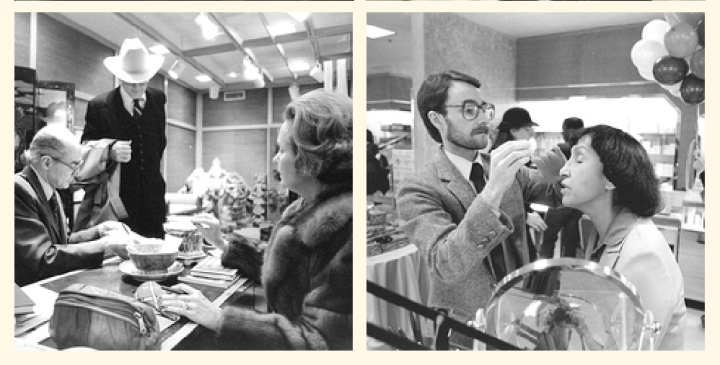

“The Store,” directed by the prolific documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman, gives viewers a glimpse into the inner workings of the flagship Neiman Marcus store in Dallas in 1982, where Wiseman and his crew spent more than a month filming the department store’s wealthy customers.

(If you’ve never seen a Wiseman film, watch this short primer from The New York Times’ former film critic A.O. Scott.)

Wiseman cuts from scenes of the sales floor, where workers sell products that only the 1% could afford, to the hidden offices of jewelers, seamstresses and merchandisers who work backstage to get products ready for sale and for delivery. The elevator transports the film crew from the unfinished basements of the store to swanky conference rooms, where executives strategize and expound their ethos for success. In one of the opening scenes, Stanley Marcus, son of one of the company’s founders, expounds on the store’s singular goal: “to make sales.”

Like most of Wiseman’s films, “The Store” lacks now-common documentary tropes. There’s no narration, no expert interviews, no expository text superimposed over the footage, no identifiers for any of the people who appear on camera. The film lacks an individual protagonist or even a classic narrative arc. Wiseman instead presents an impressionistic observation of the department store as an institution devoted to the cult of capitalism and consumerism.

Unlike most of his previous documentaries, which mostly focused on institutions that served poorer Americans, in “The Store,” Wiseman turned his camera on the elite. Neiman Marcus catered to the superrich, the kind of people who could buy a $45,000 sable fur coat — adjusted for inflation, that coat would now cost more than $141,500.

Many film critics at the time of its initial release seemed baffled by Wiseman’s choice of subject. “What is Mr. Wiseman trying to tell us about Neiman-Marcus?” one negative reviewer wrote in The New York Times. “The truth is what we see in the film. … The truth at Neiman-Marcus is that escalators run smoothly, jewelry salesmen speak reverentially, and store executives wear Vandyke beards.”

In the early 1980s, the U.S. was in the middle of a deep economic recession, triggered by the Federal Reserve’s actions to tamp down high inflation. By the end of 1982, the unemployment rate had reached nearly 11%. Perhaps the economic realities of the time influenced film critics, who didn’t see the point of making a film about rich people when so many Americans were struggling.

But Wiseman defended the film. He told one Washington Post reporter, “If you’re going to understand something about the society, you’ve got to understand something about the people with power, too. You’ve got to know something about what the rich people’s values, experiences, preferences are.”

We hope you’ll watch the film with us and then join the Econ Extra Credit team as we dig into the history of department stores, including Neiman Marcus, and the role they play in a world where so much retail shopping occurs online.

How to watch

This month’s film “The Store” is available to stream on Kanopy, for some library card holders. You can also purchase a DVD version of the film on Frederick Wiseman’s website. It may also be available to borrow from your local library.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.