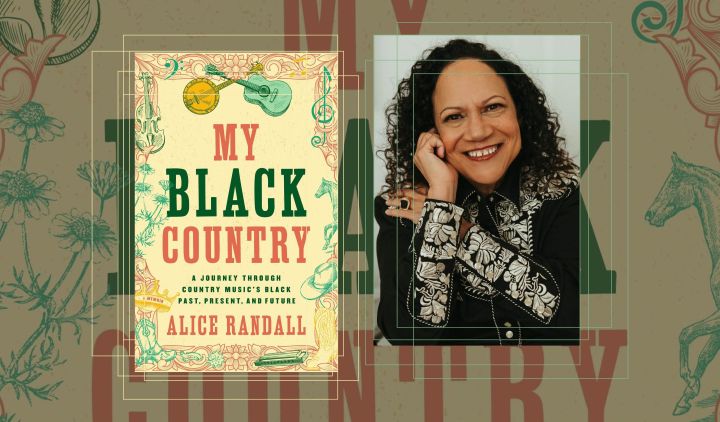

In “My Black Country,” Alice Randall returns color to the heroes, and she-roes, of her songs

In “My Black Country,” Alice Randall returns color to the heroes, and she-roes, of her songs

Alice Randall has been in the world of country music for decades. Her professional career started back in the early ’80s, when she moved to Nashville, Tennessee, to pursue a songwriting career and launch a publishing company with the hope of supporting Black artists. In 1994, Randall would become the first Black woman to co-write a No. 1 country hit with Trisha Yearwood’s “XXX’s and OOO’s (An American Girl).”

Yet she had never heard someone who looked like her sing one of her songs until 2023, during the production of the companion album to her new book, “My Black Country: A Journey Through Country Music’s Black Past, Present, and Future.” The album, in keeping with the themes of the book, is a collection of some of Randall’s songs performed by Black artists.

“Listeners thought all the heroes and she-roes in my songs were white because the singers were white,” Randall said in an interview with “Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal. “All of them I had imagined as Black, and I was willing and embrace people projecting their identities onto them, but I resisted the identities I originally imagined and created being erased.”

In her book, released as Beyoncé becomes the first Black woman to have a No. 1 country chart-topping album with “Cowboy Carter,” Randall explores the legacy of Black artists in the country music industry, including artists like DeFord Bailey, who helped shape the genre.

Randall selected the musical bridges that we played during this episode of “Marketplace.” You can find the playlist here. To hear her interview with Ryssdal, click the audio player above.

The following is an excerpt taken from the beginning of Randall’s book in which she describes what it was like to first hear the new recordings of some of her songs.

I have eaten in studios, made love in studios, suckled my daughter in a studio, rocked somebody else’s baby who grew up to win a Grammy on my hip in a studio, saw knives pulled and guns waved in studios, cussed folks out in the studio, got cussed out in the studio. Stopped by to gossip and visit with old friends and shoot the breeze, like all I had was time and no labor. Worked so late I slept on the floor of a studio mesmerized by the lights of the high-tech mix console that was never turned off, only to awaken to the sight of mice skittering across the floor reminding me that we in the South are never far from the wild. (Which made me laugh in a studio and not for the first or last time.) I’ve done a lot of things in studios.

Cry wasn’t one of them. Until my fortieth year in Nashville, 2023.

The Bomb Shelter studio has a vibe that is part old-hippy group house or grow house, part warehouse industrial, part museum of analog recording gear. You enter through a much-used kitchen that announces the gut-bucket funk of the place.

The tight quarters are chock-full of old amps, vintage instruments, classic sound mixing boards placed for maximum performance not maximum pretty. On my first visit, tornadoes were twisting through the middle Tennessee skies. Some of the musicians had left to check on dogs, or homes, or to grab kids from school. Others were ordering or making lunch. Walking through the kitchen toward the control room, I heard voices in the live room—one singing, one encouraging.

Two folks were still working. I heard it before I saw this: Ebonie Smith, dressed in stylish sweats, her part-shaved head crowned with long faux locs, was fearlessly guiding a young Black mermaid with a voice like Dinah Washington and multiple shades of purple hair through the nuances of “Get the Hell Out of Dodge,” a song I wrote shortly after my first divorce in 1991.

I had never seen or heard a Country singer who styled herself as a Black mermaid, until Ebonie invited Saaneah into the studio, after years of stalking Ebonie on Instagram, to work on what was being called the “Alice Randall Black Country Songbook” project.

I was instantly beguiled by Saaneah’s siren song. Over the years, “Get the Hell Out of Dodge,” which I co-wrote with Walter Hyatt, had been recorded at least five times. Walter recorded it himself in 1993. Honkytonk legend Hank Thompson recorded it in 1997. Then two badass babes, Toni Price, in 2003, and Eden Brent, in 2014, took a crack at the song. Finally somebody was serving up this truth with salty sweetness: you have to leave with your mind, before you can leave with your body.

Thirty years after the first recording, here was Ebonie Smith guiding Saaneah into an interpretation of the song that was retro and Afro-futuristic. Instead of luring listeners to rocks, and death, the Ebonie/Saaneah collaboration lured listeners to an understanding that liberation is first an act of the mind, then an act of the body. The fragments of the siren’s song I heard walking down the short hall were washing over me with proof of what I had long hoped: songs can be weapons. I was smiling big. Didn’t even have to say hello. I walked into the live room, looked at the two brown women working at the mike, and happy hollered, “You got a mermaid singing my song!”

Ebonie was so much more than the producer on this session. She was the engineer, composer, and activist who was bringing the magic and the thunder, not just her Grammys, her Barnard degree, and her ridiculously impressive resume. She had scrolled through her Instagram and found a Nashville-born, Country-song-loving, jazz-belting mermaid. And that wasn’t even the big moment of the visit. They were just getting started. Just breaking through the top layers of what had been painted over during previous recordings, which had effectively erased me from my own cowrite. They burned just enough incense to get all the femme and round and sweet they wanted in the room and all the edgy grunge out. Ebonie wanted to give Saaneah space and privacy to stretch into her interpretation. She invited Saaneah to take a break. She invited me into the control room. She wanted me to hear something nearer to finished.

Ebonie settled on a stool at the sound console. I settled into a couch. Ebonie pushed play. The guitar started, and then came a voice, a Black woman’s voice. Adia Victoria was singing the first words of “Went for a Ride”: “He was Black as the sky on a moonless night,” singing my words, from the place I had written those words, a Black and feminine place, a Black and Western place, a Black and haunted place. I wept tears of joy. It was the end of imagining. Sometimes the end of imagining is a very good thing.

I no longer had to imagine one day somebody who looked like me would sing “Went for a Ride.” It happened. I didn’t have to imagine someone would sing the words “He was Black as the sky on a moonless night” and they would be Black, too. Didn’t have to imagine an artist would sing those words and they wouldn’t be othering the hero of the song, they wouldn’t be talking about the Black cowboy as a novelty, as a curiosity. When the words “He rode with the best, hell he rode with me,” were sung by white [Professional Bull Riders] world champion bull rider Justin McBride, it was understood that Justin McBride was the greatest cowboy in the world and this Black cowboy in my song was good enough to be recognized by Justin but was no Justin. When Adia Victoria sang those same words, “He rode with the best, hell he rode with me,” it was one great Black cowboy acknowledging another great Black cowboy. That was the story I intended to write, and that my co-writer only barely understood, the day we worked together as staff writers in a writing room in a Country publishing house in the nineties. In the twentieth century I had to slip my best ideas in sideways.

In the twenty-first century, Adia Victoria put all my ideas on front street. She swaggered through the song, found the secret door I hid in the lyrics, and walked through it into my American West—past and present— that she alters by her Black and Country presence. Adia obliterated some stubborn old myths. With every syllable and sound, she raised our new myth. When I thought I would never get to that, I got to that. When it had come, I couldn’t bear to listen to most old recordings of my songs. I had been so whitewashed out of them, the racial identity of my living-in-song heroes and sheroes so often erased. Then, in rode Ebonie, and her posse of Black Country genius, galloping to the rescue. That’s good funky eclipsing all the bad funk. That’s my, Alice Randall’s, Black Country.

Copyright © 2024 by Alice Randall. Reprinted by permission of Black Privilege Publishing, an imprint of Simon & Schuster LLC.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.