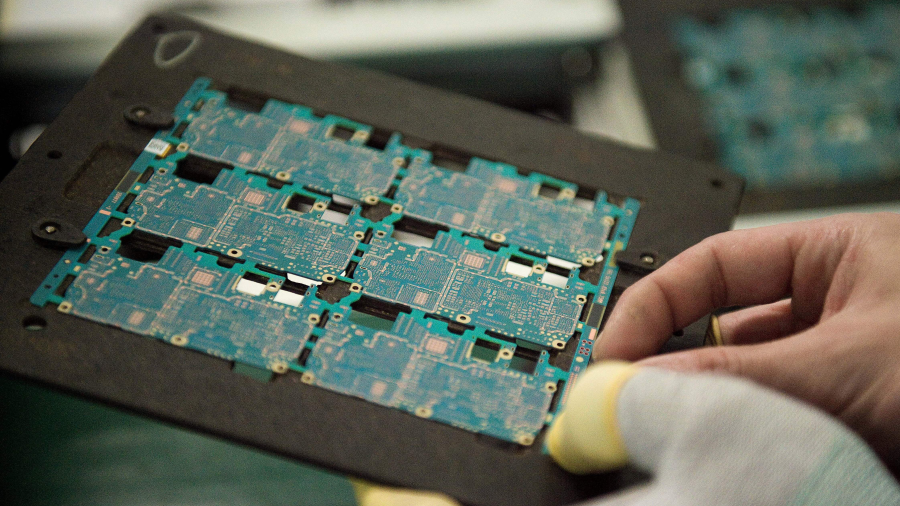

No chips. Fake chips. The computer chip issues are still with us.

Let’s talk about computer chips. We’ve told you that they’re in short supply — because of COVID and materials shortages and shipping problems, and because a lot more people have bought digital devices during the pandemic.

What sometimes happens when there is low supply and high demand is counterfeits appear on the market. These could be chips taken out of old electronics and resold as new, they could be chips mislabeled so they can’t actually do the job they’re needed for.

Sometimes the fake chips work — to a certain extent — and sometimes they don’t work at all.

I spoke with Bill Cardoso, CEO of Creative Electron, a company that uses X-rays to inspect chips and see if they’re real. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Bill Cardoso: Especially in supply chain disruptions, like the one we’re experiencing right now, there’s a shortage of these authorized components. So companies go to what we call the gray market to look for chips. And that’s where the opportunity for counterfeits starts. So you buy a component, and if you look from the outside, it looks exactly like a legit component that you want. But the internal structure is different — it’s something else. And COVID presented a unique opportunity for counterfeiters because we’ve seen drastic reduction in supply. A lot of those factories were shut down because of COVID, and a huge spike in demand, and counterfeiters are just flooding the market with fake chips.

Marielle Segarra: What can you see on an X-ray that’ll help you tell the difference between a fake chip and a real chip?

Cardoso: We look at connections inside the chip, and if those connections are not correct, based on the documentation of what the component’s supposed to do, we can determine that it’s a fake component.

Segarra: And do these counterfeit chips work?

Cardoso: That’s a very good question. Sometimes they do. There’s one common application of counterfeit chips in the military and aerospace markets. And the difference between a military spec and a commercial spec, sometimes it’s just one letter in the package of the chip. So what counterfeiters do is they erase the commercial — the “C” — and replace it with an “M.” And now that’s a military component, and the price went up by 100 times. So electrically, under normal conditions, it’s going to work exactly the same. But at the extremes where the military component should perform, if it’s on a fighter jet or a nuclear missile, that’s where you can have a failure in the worst possible time.

Segarra: How does the increasing number of counterfeits affect manufacturers and retailers? Do they even know that these chips don’t work before they sell the products? Or are they sort of tested first before they end up on shelves?

Cardoso: We’ve had more and more customers now approaching us to help them set up a counterfeit detection program. A lot of these companies never had to worry about it, so they don’t have a counterfeit mitigation program in-house, and now they’re setting one up. A lot of companies are not even doing that, which is going to result in product being shipped that either is going to fail before it ships or it can fail at the customer side.

Segarra: And if a manufacturer buys, like, a bunch of counterfeit chips, what recourse is there for them?

Cardoso: Sophisticated manufacturers have language in the contract when they buy chips, and the contract usually says something of the nature that these chips are legit, right? And if something happens, it’s the supplier’s fault. So the manufacturer has some legal recourse.

Segarra: Is there any sign that this shortage and that the volume of fake chips will change anytime soon?

Cardoso: If I had to bet, we should be getting out of this supply chain shortage later in 2022, maybe early 2023. So that’s a problem we’re gonna have to deal with for at least another year or so.

Related links: More insight from Marielle Segarra

It can be hard to suss out which chips are fake just based on whether a product works in the moment. As Cardoso pointed out, that can happen with military-grade chips. You wouldn’t know they’re fakes until they failed.

You can check out this story from Ars Technica that touches on that idea and also shares a guide on how to recognize a fake chip by how it looks, in case you’re curious.

That Ars Technica story says that fake chips are less of a problem for the big tech companies, which have a steady and secure supply of chips. But for smaller companies that buy from distributors, that’s where it becomes an issue.

The chip shortage has affected so many industries. Car companies have had to halt production at some of their factories because of it. Medical device companies are having trouble getting chips for pacemakers and ultrasound machines. And appliances like ovens and refrigerators, which often have electronic display boards and other parts that use chips, are in short supply too. We’ll link to a story from The Wall Street Journal last week about people who moved into a new apartment or house and had to wait three months for one of their major appliances to arrive.

So they got creative. But … yeah, it’s not ideal.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

Every day, the “Marketplace Tech” team demystifies the digital economy with stories that explore more than just Big Tech. We’re committed to covering topics that matter to you and the world around us, diving deep into how technology intersects with climate change, inequity, and disinformation.

As part of a nonprofit newsroom, we’re counting on listeners like you to keep this public service paywall-free and available to all.

Support “Marketplace Tech” in any amount today and become a partner in our mission.