Chapter 2: The compliance machine

Americans who turn to public assistance have something in common: They’re poor and vulnerable. But that’s where the similarities end. There’s a wide range of work experience and education among them — and often very different circumstances that landed them on welfare.

But when they walk through the door of a welfare office seeking cash aid, they often come up against a system primarily focused on ensuring that they meet work requirements mandated by federal law, whether the required labor is helpful for their particular circumstances or not.

A single mother of two from Chicago learned this the hard way. She had been working and taking classes to become an addiction counselor when her life fell apart. The father of her youngest child assaulted her so badly, it put her in the hospital. Worried for her safety and the safety of her children, she fled to Milwaukee and signed up for welfare, hoping it would live up to the promise of providing employment and self-sufficiency.

Instead, she ended up in a Kafkaesque maze of “job readiness” classes she didn’t need, work assignments that earned her less than the equivalent of minimum wage and leads for warehouse jobs that didn’t fit her resume. When her life hit another crisis, things hit rock bottom.

Host Krissy Clark examines the roots of this cookie-cutter regime and discovers that a fundamental part of the problem lies in how the landmark 1996 welfare reform bill measures success — which has little to do with helping participants gain family-sustaining employment.

Krissy Clark: Just a note before we start, this episode contains some short descriptions of physical violence. The work requirements that exist in cash welfare programs today across the country, thank you very much the requirements that are enforced daily by state and local governments or the private contractors they hire.

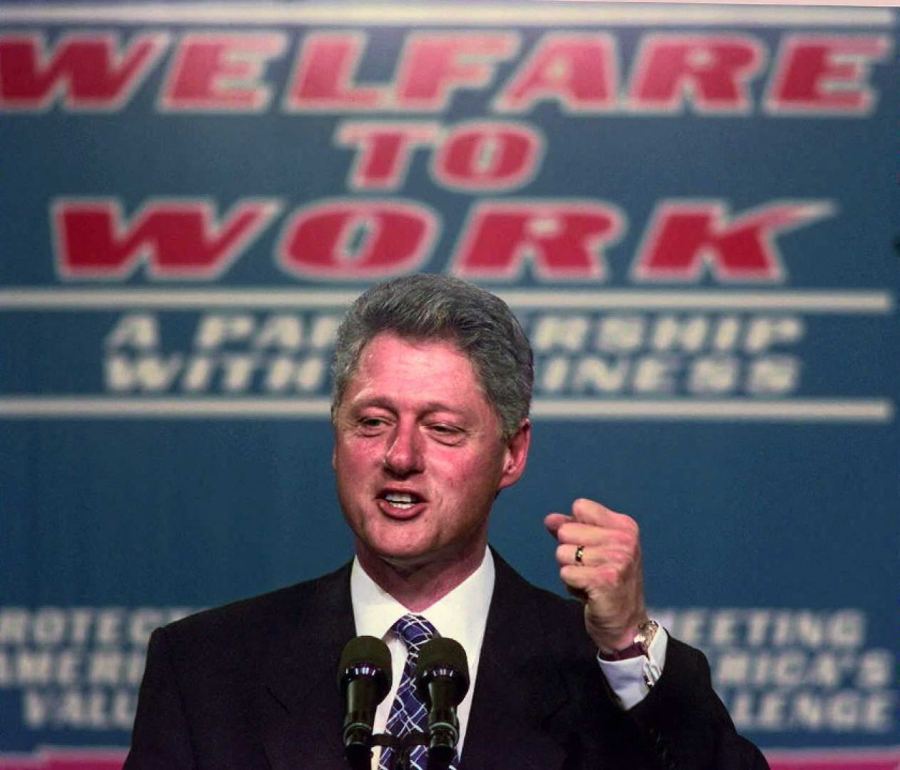

Bill Clinton Speech (1996): Thank you, Mr. Vice President, members of the Cabinet.

Krissy Clark: Those requirements came into being in 1996. On an August day in the White House Rose Garden, when President Bill Clinton signed the so called welfare reform bill into law.

Bill Clinton Speech (1996): Today we are in the welfare as we know it. But I hope this day will be remembered not for what it ended. But for what it began. A new day that offers hope, honors, responsibility, rewards work.

Krissy Clark: On that day, halfway across the country in Chicago, a young woman named Darnetta Harris had no idea how tangled up she was eventually going to get in the new Welfare to Work system that President Clinton and Congress had just created.

Darnetta Harris: It was just me and my daughter, but I was the one to say, I’m gonna rely on the systems to take care of me.

Krissy Clark: Diana had just turned 20. And as a young single mom, she knew about the old version of welfare before this law had passed. Her family been on it for a while when Diana was a kid, and had helped her net out when she’d had her baby. But she had a lot of ambition…

Darnetta Harris: Saying the programs are not helpful. But I don’t want to be another statistic. I want it better for me and her so I did what I had to do.

Krissy Clark: She was doing a lot, going to community college, working, caring for her child. In the back of her mind, she had one big dream.

Darnetta Harris: I’ve always had a passion for helping people. Or I had this mindset that I wanted to help people learn that I grew up in the projects of Chicago. I watched the crackheads and alcoholics that I had to grow up around and just like the people was then they was becoming the addicts was becoming younger and younger. How can I help my people will just help people period I wanted to help people period.

Krissy Clark: She decided she wanted to become an addiction counselor. Darnetta chipped away at this goal. She did an internship at a drug treatment clinic, another at a residential rehab facility to pay the bills. She had various jobs like being a teacher’s assistant at a daycare, but on her way toward her dreams of helping people. Something happened to Darnetta that left her in a situation where she needed help. The trouble started when she was in her late 20s and found herself pregnant with a second child. The father got abusive.

Darnetta Harris: My hardest part is that he beat me up the whole nine months I was pregnant with his child he beat me up. We wasn’t together at I had the baby but he used to manipulate me with the son. I want to come and see my son or I can get in my mama house. Can I stay here you can sleep in your son’s room you can sleep here with me. Blah, blah, blah.

Krissy Clark: It all came to a head one day when he asked Guyana to pick them up from work.

Darnetta Harris: Yeah, I could do that for you. So I guess I didn’t get downtown fast enough for him in Chicago. So he ended up making it back to my house. He come to my house. He said what happened to you start arguing with me. He didn’t like my response. I turned around. He hit me in my eye. He broke a bone in my eye. My son was two years old. My son can tell you this story as it happened yesterday. So he took me to the hospital. Me being afraid, didn’t say anything. Police came to ask me. I had to get stitches as I have two three reconstructive surgeries. If I look down to my left and my right to Division at the bottom is gone.

Krissy Clark: She tried to cut off contact with her ex. But one day after she’d come home from work and was making her kids dinner, he broke into her house.

Darnetta Harris: After that. I was like I got to go.

Krissy Clark: She felt like there was nowhere safe to be. She scrounged enough money to rent a U haul packed up her two kids and fled. She didn’t tell anyone in Chicago she was leaving until she was already gone. She drove 90 miles up the shore of Lake Michigan to Milwaukee. She used the little savings she had to put down rent on a new place. She knew just one friend in the city had no close family, no job, no personal safety net.

Darnetta Harris: I had nobody right. I had to start over No. So I tried to I needed a steady flow of some type of income. I can’t just sit here and expect for somebody to take care of me I need a job.

Krissy Clark: The welfare law that Congress created and Bill Clinton signed when Darnetta was 20 that he said was all about helping people get jobs,

Bill Clinton Speech (1996): A system of incentives, which reinforced work and family and independence.

INTRO

Krissy Clark: Those were all the things that Darnetta was looking for work and independence and the ability to protect her family. She just needed some temporary help to get herself in her two kids back on their feet. She wanted a job. But there was the politician rhetoric about honoring personal responsibility and rewarding work. And then there were the actual details of what this welfare reform law was going to require people to do, and how it was going to be enforced. And as Darnetta would soon discover, those details, didn’t seem to have much to do with her ideas about work, and independence and family at all. Welcome to The Uncertain Hour. I’m Krissy Clark. This season, The Welfare to Work industrial complex, who it profits, like really profits, and who pays the price, the goals of the Welfare to Work system, they’re written right into the welfare reform law, one of its main purposes is to, quote end the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation and work. But further down in the text, is where the rubber meets the road. The welfare law doesn’t just promote work as an avenue toward economic independence, it requires it. And as soon as you make something mandatory, for it to mean anything, you’ve got to define what it is create a system to track and measure and verify whether it’s happening, and a system of enforcement and consequences if it doesn’t happen. Those are the details that the welfare reform law spells out. What kind of work actually counts how the government’s going to hold individual people on welfare accountable for doing it, and how state and local governments and the private companies they contract with will be held accountable for enforcing those rules. And when all the details of that law, converge on an actual human life, things can start to go really sideways. On this episode, I want to tell you the story of Darnetta. And some of the things that happened to her when she walked through the door of the privatized Welfare to Work system in her most vulnerable moment, I want to tell you about some of the people who’ve worked inside that system, and how they feel about it. And I want to tell you about some of these small bureaucratic details written into the welfare reform law, that spell out how its goals are going to be measured and enforced. And the impact those details have had on many of the people who turned to welfare in ways that sometimes seem to just amplify their problems. Chapter Two, the compliance machine. When Darnetta fled Chicago and landed in Milwaukee to escape the violence of her ex, she had to start her life over, she needed a job. But first, she needed toilet paper, dish soap bus fare to be able to get to a job interview, which is what brought her to apply for cash welfare, or what’s officially called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. It goes by different names in different states. In Wisconsin, it’s known as Wisconsin Works. The goal is similar to the goals of most state welfare programs to help get people into work so they can provide for their families and become self sufficient. And when Darnetta heard about what Wisconsin works was supposed to do, it sounded like exactly what she needed. The money part would be helpful, yes, 600 or so dollars each month to help her get back on her feet. But also that part about work that was right in the name, Wisconsin Works. Even the program’s nickname sounded worky W2, like the IRS employment form.

Darnetta Harris: With W2 I knew that it’s about job search. And that was one of the places that gave you job leads on anything I needed was a push in the right direction. A lead give me a lead. If you can get me a lead somewhere, then I can try to make it work the best for me.

Krissy Clark: And in the middle of all the trauma she was trying to escape in Chicago and the money stresses she was living with in Milwaukee. She was hopeful about what kind of job she could get where her future could take her. She was ready for a new start.

Darnetta Harris: I was nervous but excited at the same time because I felt that I was doing what was best for my children and me to be safe, be considered. At peace I needed peace.

Krissy Clark: She went to the welfare office she was assigned to based on where she lived in Milwaukee. Like all the welfare offices in the city. This office was outsourced to a private company. First a nonprofit. Eventually, while she was there a for profit took over the contract. When Darnetta first enrolled, the intake workers asked her questions about her family, her income, her assets and a bunch of stuff about work.

Darnetta Harris: What you hope to accomplish, what’s your goals. How do you plan on achieving those goals. What steps are you going to take? Stuff like that. I let them know my employment background also had a pre-resume already done up. Right? So it was It wasn’t like I was coming in, like, I don’t know what I want to do with my life. I had to goals set, I had two options on the plate.

Krissy Clark: One option, that dream she’d been working toward through her 20s becoming an addiction counselor. She told them about the certifications she’d already gotten in addiction studies.

Darnetta Harris: I have a basic certificate and an advance certificate.

Krissy Clark: But did Wisconsin accept Illinois credentials? She wasn’t sure. She was trying to figure out all the logistics now that she’d moved to a new state.

Darnetta Harris: You know, how can I take my addition study certification here? Would I have to start over blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

Krissy Clark: And she wanted to stay flexible. So she’d been thinking about another path too.

Darnetta Harris: So having me my own restaurant, I was the one always in a kitchen helping my mom. While you’re eating, you end up letting off some of that sting. You end up feeling good for what a laughter a kind gesture anything.

Krissy Clark: She wanted to share that healing power of food with others. She told the people at the welfare office she’d even been thinking about a name.

Darnetta Harris: So in remembrance of my mom it is gonna be Jackie’s Place.

Krissy Clark: Darnetta was excited about either of these paths, opening a restaurant or addiction counseling. Paths she could envision supporting her family on doing something she was passionate about. Darnetta says the caseworker nodded and listen, entered some stuff on a computer screen. And then she said something that did not seem to connect to anything Darnetta had just said. She told Darnetta she was placing her at a local food bank.

Darnetta Harris: To do what? So she gave me a description of the job in stocking boxes. And is that.

Krissy Clark: Just stacking boxes like you would have just been doing kind of manual labor basically?

Darnetta Harris: Right.

Krissy Clark: Oh, and also her case manager explained, this wouldn’t be an actual paying job,

Darnetta Harris: Because they call it volunteering because they consider it as volunteers. It’s free labor pretty much.

Krissy Clark: Darnetta looked at her caseworker.

Darnetta Harris: Did you not read my resume? I’m very skillful. This is not what I do.

Krissy Clark: Darnetta like the kind of work that was going to get her closer to either of her goals. It sounded like a step backward. And in this moment, Darnetta was coming up against the first of one of those little details about how the federal welfare reform law works. That would come to confound her. Because the law wasn’t particularly interested in whether Darnetta was eagerly trying to pursue her dreams of becoming an addiction counselor, or opening a restaurant. What the law was concerned about was that if she was going to get welfare, she needed to immediately start doing a certain number of hours of work activities to meet the laws work requirement, having a paying job could count. But since she didn’t have one of those yet, she was going to have to do some other kind of work activity, instead. The federal welfare law has a list of 12 activities that qualify things like job search, short term vocational classes, community service, or unpaid work experience. Darnetta’s case manager was saying that one of the main things she’d lined up for Darnetta was this unpaid work experience in a food bank warehouse, packing and stacking boxes of food for several hours a day?

Darnetta Harris: I’m like no. No, no, I can’t do that, that I actually just told them. I can’t do that. I can’t do that. I’m not going to do that.

Krissy Clark: How did they react when you said that?

Darnetta Harris: She was like, well, you won’t get no check.

Krissy Clark: As in no welfare check. The case manager was telling her if she didn’t do this assigned work activity…

Darnetta Harris: You’re not being compliant.

Krissy Clark: They said you’re not being compliant?

Darnetta Harris: They said I wasn’t compliant.

Krissy Clark: Darnetta held her ground.

Darnetta Harris: Yeah, I will speak up for me. I said, let me speak to the supervisor. I need to speak to the surpervisor before i leave here. So I spoke to the supervisor. She said, what’s the problem? I told her the problem. She was like you got your resume? So I gave it to her.

Krissy Clark: Eventually, dinette convinced the supervisor to reconsider. The supervisor said she’d assigned Darnetta to do work experience in a different nonprofit instead.

Darnetta Harris: I said, and do what? She said, you will be an assistant down there. I said, what kind of assistant?

Krissy Clark: You’ll be a program assistant, a supervisor said helping file paperwork working in the office.

Darnetta Harris: So I said, Okay, I’ll be there.

Krissy Clark: She tried to find the bright side of this. At least it was in an office. But it still was unpaid labor. And that felt unfair to Darnetta. That was not the only work activity Darnetta was required to do. There were the soft skills classes that at one point she was required to spend 11 hours a weekend.

Darnetta Harris: I had to learn computer skills although I had computer skills.

Krissy Clark: But she figured or maybe they can help me learn a new software that I’m not so good at.

Darnetta Harris: Okay, I’ll say this because I’m not good at Excel, you could teach me how to do PowerPoints. And now today, I can work a PowerPoint, you get what I’m saying, even though it was demeaning sometimes it felt demeaning to me. I had to end up making things work for me, I got a certificate for somewhere around.

Krissy Clark: But some of what she was required to sit through, it was harder to find a bright side to it.

Darnetta Harris: Just telling you how you suppose to dress, the proper language, etiquette, resume writing, they taught me that even though I produce the resume, they sent me through that the whole motion. They did the little mock interviews, although I showed them my job skills. I’ve had interviews, but I had to go through all that tedious things. It was tedious to me, I’m 30 some years old are you serious?

Krissy Clark: During most weeks, there was one more required work activity she had to do to fulfill all her hours, actually searching for jobs. This remember, was part of why she’d been excited about welfare in the first place. She’d heard it could help her get job leads. And it’s true. At the welfare office, they’ve given her a big stack of job listings. But the kinds of jobs that were listed.

Darnetta Harris: Factory work, a lot of factory work.

Krissy Clark: Stuff that at the time, paid barely over minimum wage, $8 or $9 an hour, she knew that wasn’t going to be enough to support her family of three on. So that ruled out a lot of the job leads she was getting at the welfare office. And then others were in places she just couldn’t realistically get to.

Darnetta Harris: You can only go so far. You don’t have transportation besides the bus, some jobs way out you need cars.

Krissy Clark: And you didn’t have a car?

Darnetta Harris: I didn’t have a car at the time.

Krissy Clark: Still, she had to submit job search logs each week, showing she’d looked for jobs for the assigned number of hours, listing each job she had applied for how long she’d spent applying for it, and the contact info for the company. So her caseworker could call and verify if she was applying for a job in person, she had to mark down what time she left the house, how long it took her to get to the place, she was applying for a job, how long it took her to fill out the application, what time she turned it in there, what time she left to go to the next potential job over and over. This was back in 2010, 2011, the economy was still climbing out of the Great Recession. Darnetta says, sometimes it was hard to find enough suitable jobs to spend 10 or 15, or sometimes 20 and 30 hours a week applying for.

Darnetta Harris: At that time, everybody wasn’t hiring or didn’t need the help that they need now. So it was like it was becoming repetitive. You know just start putting down anything just so they can just you can get the check.

Krissy Clark: Darnetta was finding that welfare was a lot of hassle. So many forms, so many hoops to jump through. She says they made her feel like a dog.

Darnetta Harris: I used to have a dog, sometimes when you, you waddle that little bone or treat for them to make them do a trick. Because they want their treat they’re gonna do whatever you say. That’s, that’s that’s what I felt like, you’re gonna do whatever was hell you to do in order to get some money. That’s a problem for me. That’s how I felt. That’s how I felt.

Krissy Clark: And did you tell them about your the domestic violence situation that you had had to flee in Chicago? Like, did they understand that you were just coming out of a very traumatic situation?

Darnetta Harris: I told them that. You know how you opened up your story. You had to sell it all over again. I had to do that several times. That’s heartbreaking when you’re trying to move past it.

Krissy Clark: And did they give you any resources or help in that?

Darnetta Harris: Nope.

Krissy Clark: In Wisconsin, case, managers can reduce or waive work activities in cases where domestic violence is an issue or offer other supports, but it’s not a given. And then, not long after Darnetta enrolled in welfare. There was another family crisis.

Darnetta Harris: They took my son from me.

Krissy Clark: I’m not going to get into the details to protect her son’s privacy. The situation was complicated, like life often is. But the outline is Darnetta says one day soon after they’d fled Chicago from Milwaukee. Her son was acting out.

Darnetta Harris: I was so fed up and I went to discipline him. Girl, just like everything I wooped him just like old school wooping.

Krissy Clark: Child Protective Services got involved.

Darnetta Harris: They had to do what they had to do.

Krissy Clark: During that a temporarily lost custody of her son. He was put in foster care and the process of trying to win custody of him back. It was a lot.

Darnetta Harris: Child Protective Services get these demands on you. They didn’t deem me as a bad parent, but they felt like I needed to do other things in order to get my son back, I have to go to parenting class, I have to go to this, I have to go to court. I have to take my son to this therapy, he comes for a visit on his day or I have to go to a family therapy. So this is why I’m still trying to find a job trying to do W2, the requirements of W2.

Krissy Clark: And this is one of those moments, when you see how the details of welfare work requirements can sometimes interfere with the life of someone who’s already struggling in ways that only amplify the struggle. Because all those court appearances and therapy visits, those very important things that Darnetta was doing to try to get her son back to try to heal her family. They started getting in the way of her required work activities. When she met with her case manager again, Darnetta says she told them about the situation with her son, and that it was making it hard for her to keep to a regular schedule.

Darnetta Harris: I explained these things I explained my barriers to the worker at the time. This is what I got to do.

Krissy Clark: But Darnetta says her case manager kind of blew it off.

Darnetta Harris: Not listening to my barriers. What days you have to go to court? I don’t know, when they tell me I have to be there. She wrote it all down. She say okay, well, you have an appointment is that I can’t come this day, I gotta be at court what time you get out of court out who’s to know that? I don’t know. I don’t know. Then I have to you know, well headquarters far. So I had to take I’m on a bus. So that’s three, four buses. So a lot of times I couldn’t meet, I cannot connect, I can always meet their appointment days.

Krissy Clark: And on the days that she didn’t make it to one of her work activities, there could be consequences

Darnetta Harris: They start sanctioning me.

Krissy Clark: According to the federal welfare law, when you miss even one hour of its required activities, you can get sanctioned, unless you can convince your case manager that you had a good cause for missing the hours. In Wisconsin, if you don’t have a good cause, and you don’t make up the hours right away, your check gets reduced by $5. For every hour you’ve missed, which I want to point out is more per hour than most people are effectively earning for those work activities. A required court appearance can qualify as a good cause for missing hours. But there are gray areas. Like what if you miss your bus after the Court appointment and miss even more hours. It’s up to the case manager. And if they think it fits a pattern of absences and they don’t think your explanation is quote reasonable. They can require a lot of documentation and paperwork to backup your reason. Darnetta says she started getting in arguments with her case manager about what was a good cause and what wasn’t

Darnetta Harris: Like I’m trying to hit it. You suppose to be here at this time, I tried to call your phone you didn’t return the call to me. I came down here. You wasn’t here that day. That’s what it was.

Krissy Clark: And her checks kept getting reduced.

Darnetta Harris: It’d be like 20-25 hours missing like one time I got a check for 500 I was like what the fuck.

Krissy Clark: Darnetta felt stuck. If she didn’t want her check to get reduced. She had to make sure she did all her required hours of work activities. But her required work activities were hard to complete with all the things she had to do to get back her son.

Darnetta Harris: And my point is I gotta get my son back. Regardless of what you’re doing to me, I’m not going to let you all stop me from doing what I have to do to get him back into my care

Krissy Clark: After more than a year Darnetta did eventually get her son back, which was of course the most important thing. She was relieved and grateful. But when he came back, she was in worse shape financially to care for him. After all the sanction she’d gotten.

Darnetta Harris: Which caused less income coming in. It was a scramble, either my phone got cut off, my home phone got cut off, or my light bill was getting piling up that will fall behind on how to try to catch up to because I don’t want no notice in the mail. I tried to make put something on it $20-$30 here, which will start to affect my credit because they feel like my paying it all the time. I was stressed stressed out because I’m trying to deal with this w two stuff. I’m trying to provide food I’m trying to be a mom.

Krissy Clark: I should say we reached out to the private company that oversaw the office that are not a went to for much of her time on welfare and Milwaukee. The company didn’t respond to our requests for comment. We also reached out to the state agency that runs welfare in Wisconsin to ask about Darnetta’s experience. They declined an interview but said in a written comment that if someone’s being repeatedly sanctioned each month, contractors are expected to review the work activities they’ve been assigned work to identify any barriers and offer accommodations to support, quote, successful activity completion. They also said state policy requires private welfare agencies to work with participants to assign work activities that are specific to that individual’s needs and goals. And that the use of unpaid work experience like that box packing in the food warehouse, or the office work that Darnetta was assigned to, has declined in the past few years. But that for some participants who’ve never had a job before, it can be a useful way to build the skills that are required to retain employment. But for Darnetta, that was not her experience on w two, for her, the sanctions, the busy work, the menial labor, packing and stacking boxes that she was first assigned to do. The general feeling of counter productiveness of it all. It made Darnetta wonder, why was the system like this? What was going on in the minds of the people in the W2 office?

Darnetta Harris: Is this just a job for you? Or do you really care about the people in this community that come here for help?

Krissy Clark: Like, did they see how unhelpful this work requirements system seemed to be? Turns out, some of them did. That’s after a break.

Amy Scott: The southwestern United States is more than two decades into a drought made worse by climate change. And as rivers dry up, private investors are buying water rights. But should people be allowed to profit from the crisis?

Mathew Diserio: The biggest emerging market on Earth is water infrastructure and water resources in America. It’s a trillion dollar market opportunity.

Amy Scott: This season, How We Survive investigates how people are adapting to and cashing in on the climate crisis, and how it’s reshaping the future of the West. Listen to How We Survive wherever you get your podcasts.

Krissy Clark: We’re gonna get back to Darnetta’s story in a moment. But I want to turn to someone who shared many of Darnetta’s frustrations with the Welfare to Work system, the work activities, the sanctions, all the hoops and forums and general sludge autocracy. But this person was experiencing it all, from a really different vantage point.

Debra Gary: It’s Debra Gary and I worked as a case manager for I will say, close to 12 years.

Krissy Clark: Debra and Darnetta didn’t know each other at the time. But Debra was working in that same private welfare office that Darnetta was going to a decade ago, when Debra first became a welfare case manager, she had big dreams for how she was going to use this system to help women who were struggling,

Debra Gary: My goal as a child always been, I’m gonna save the world. I’m gonna make a difference.

Krissy Clark: And she saw working in a welfare office as a pretty good way to do that.

Debra Gary: My idea was like, Oh, I get to work close in the community, I get to help people along the way, and you know, get a job. So I have faith, like, oh, I can make this work for people.

Krissy Clark: And she says, at first glance, the way welfare operates today, the whole work requirement model, it made some sense to her.

Debra Gary: My editor was just like, okay, this is the time to work. Like if you’re talking to w two when you rather get a job and come to W2.

Krissy Clark: So why not give folks some structure a to do list of work related activities to help them get a job. And Debra says, there were some people who seemed to get genuine use out of the things they were required to do.

Debra Gary: All clients when they come in and be like, I found a job I’m making $15 an hour, I’ll be graduating in the next four months. I’m gonna invite you, I put a down payment down on me a car and toodle loo, I don’t need ya’ll no more! Bye!

Krissy Clark: And that would happen occasionally?

Debra Gary: There are a few in between. I would say two and half to three out of ten.

Krissy Clark: Debra says it was usually when someone was already in a pretty stable position, maybe living with another adult who could help with childcare and rent, not already behind on their bills, not experiencing some kind of trauma.

Debra Gary: So those folks that already have a support system in place that will have a support system in place are the ones that tend to do to do good and thrive more. They fit the cookie cutter script.

Krissy Clark: But what would happen more often Debra told me was that people did not fit the cookie cutter script for all sorts of reasons. Take what happened to Darnetta. Coming to W2, while she was still dealing with the trauma of domestic violence and her own struggles parenting her son, Debra says, piling required work activities and sanctions on top of someone in the middle of all that was just too much. And she says that happened a lot. Domestic violence was a problem. In many cases she saw.

Debra Gary: We would literally have women come in, you know, with black eyes, broken bones, hair pulled out, whatever happened to them stab marks, I mean, you name it, we’ve seen it all.

Krissy Clark: According to a number of studies, 50 to 60% of women participating in cash welfare, have experienced domestic violence at some point in their lives, a rate almost twice as high as the rate for all women in the US. And like I mentioned before, there are state welfare policies meant to direct people who were actively experiencing domestic violence towards resources for support and give them more latitude with work requirements in the short term. But how exactly that was handled, could be up to an individual caseworker’s discretion. It depended on who was managing a case and how much empathy, patience or attention they couldn’t give it. While they were juggling the day to day tasks of assigning work activities and monitoring compliance. And sometimes the Debra says case managers would just flat out miss something big and hard that was going on in someone’s life.

Debra Gary: Yeah, those are a lot of people that slipped through the cracks, whether it was simply because they didn’t want to, you know, disclose that or they didn’t know how to speak to someone about it. Then sometimes there were no bruises we’re okay, on the outside, they appear to be able job ready, so to speak. But when you really start dissecting things, then it’s it’s alot. I mean, they that job ready, they don’t need to sit in this class, they do not think these skills and they need to go on a whole another route. They need to be in some sort of counseling, you know, it’s gonna take a lot before they are able to get a job and maintain it.

Krissy Clark: Health issues, mental health issues, loss of a loved one. So many reasons. People didn’t always fit the cookie cutter script. Another reason? Debra says there were a lot of people who clearly lacked just basic education. There was the woman Debra met, whose case manager had assigned her a bunch of hours doing job search, the woman had turned in pages and pages of logs documenting all the jobs she’d searched for.

Debra Gary: She was like Miss Debra less you missed nobody even call me back. Nobody call you back? She was like even Popeye’s didn’t call me back. Burger King, she was like i went to all the restaurants. She was like I even went to a laundromat, and they didn’t call me back.

Krissy Clark: Debra had a pretty good guess about why this woman wasn’t getting any callbacks. Once she looked through the job search logs that she’d turned in, based on how she’d filled them out. It seemed she was barely literate. And Debra says that was common.

Debra Gary: When you look at their handwriting. And when you look at the way they’re spelling things, and in that only knows how they filled up that application. You know, like they’ll put e-n-d for i-e-n. It’s heart wrenching. Nobody’s gonna call them back. So it was just empty work. And she looking at me for the answer. And I don’t have it. So I was like, they missing out. You know, I just thought it I missed out on a really good worker. So because I didn’t know what else to say.

Krissy Clark: What she did not say. But what was going through Debra’s brain was like, why in God’s name were some of these people getting assigned to search for jobs? When they can barely spell or write a sentence. They needed a whole other level of help. Debra says she wanted to be able to just let these participants focus on learning to read and write send them to a high school equivalency program full time.

Debra Gary: Because people are not dumb. They just disenfranchised and say what can she do you know she’s a caterpillar let her become a butterfly.

Krissy Clark: But helping caterpillars turn into butterflies was a tall order given the way welfare works today. For most participants, going to school to get a GED must be combined with at least 20 hours a week of other work activities. So it’s hard to juggle. Deborah was frustrated by the moments when people who seem to need basic education or trauma counseling or treatment, or instead being asked to comply with a bunch of work activities that seemed like they were just not focused on what they really needed. And then there were the times when people were ready and willing to start focusing on work, but the work activities they were getting assigned, just weren’t helping them get to a family supporting job. This was true for Darnetta too remember, she already had some college credits and certificates behind her a clear idea of what she wanted to do for work and a solid resume. And yet she was assigned to do things that felt like busy work, taking resume writing classes and packing boxes of food in a warehouse for less than the equivalent of minimum wage.

Debra Gary: You boxing food, where’s the skill? What are you learning? They are not less competent just because they came via W2, they need the money more so than anybody. So why not? You know, at least the minimum wage or whatever state they’re in at least that for their activities.

Krissy Clark: Debra wanted to see more focus on individualized training, getting people set to pursue the careers they had a passion for, like Darnetta’s passion for addiction counseling.

Debra Gary: Let them get certified, so that when they do leave the program, they have that skill that they love so much. How about that? How about budgeting some money in the budget for something like that.

Krissy Clark: But that is not where much of the money went in the budget. In the latest available data from 2021. Wisconsin spent just 0.5% of its welfare dollars on education and training. It spent much more of its welfare dollars on things like program management, administrative costs, and quote, additional work activities. That is money paid to companies like the one Debra worked for, and the company she subcontracted for America works and other private welfare agencies like it money, they got to assess welfare recipients to see how job ready they were to provide unpaid work experience and job search assistance and job readiness support to monitor and enforce and verify whether they were actually doing the work requirements. And if they weren’t to officially sanction them and reduce their check or require them to go to great lengths to prove they had a very good excuse, why they should not be sanctioned. Debra told me about people who’d missed work activities, and had to get documentation from the dentist about a toothache or from a doctor about an earache. And then there was the story about this one mother who called her one day.

Debra Gary: She called she had an appointment, I’m not going to be able to come in, okay, fine. What’s going on? Are you okay? This, you know, meeting her? No, not actually. Well, what’s going on? Can I just call you back? She called back. She was like my son was killed that night. She was just devastated. But still thinking ahead. Like as a mother, she was like, I’m not gonna be able to come into this appointment. But I really, really need my whole check. So can we reschedule because I have other kids I need to think about. Now, it wasn’t that calm or that simple. This is just, you know, from memory, but you know, she could have been sanctioned for that.

Krissy Clark: Like I said before, case managers do have some leeway about when missing a work activity merits a sanction, depending on whether or not a person has good cause. A death of an immediate family is a good cause. And case managers can excuse someone for a few days. But again, there’s judgment involved. If the case manager feels like the absence fits a pattern and doesn’t believe the reason they might give a sanction until the person can give some proof, like a police report, or an obituary. Debra says she did not require this woman to provide any of that. But the idea that she could have disturbed her.

Debra Gary: It would have been, for the most part, folks are not lying line about their kids being shot down on the street the night before, you know?

Krissy Clark: Yeah, yeah. Welfare to Work programs are often described as being training for regular paying jobs. But as I listened to Debra, I started thinking about how my father-in-law died recently, and I took time off work to attend the funeral. It did not occur to me at the time what a privilege it was that I didn’t need to provide a copy of his obituary to my boss. In order to get that time off without punishment. Debra was once really hopeful about the Welfare to Work system, and how she could help families in need. But after working in it for 12 years, assigning and monitoring and verifying people’s work activities, and penalizing the ones who fell behind, she’d come to this conclusion.

Debra Gary: The system is just fucked up and broke. We’re putting money in the wrong place. It needs to be a direct payment to people. People don’t need to be worried about, oh, if I miss a day, I’m not gonna be able to make my rent. They have no other options than to try to fit this thing in whatever it may be, because we said they have to receive the small amount of money, and they’re just gonna be on a hamster wheel, it’s just gonna continue and continue because they we’re not getting to the root of the problem.

Krissy Clark: And there are a lot of people who’ve come to the conclusion that the problem is facing individual folks who turned to welfare can be exacerbated by a more fundamental problem. The federal law that quote unquote, reformed welfare back in 1996, and how it was written, this little flourish of policy embedded in the law that would go on to confound so many people, something called.

Jeanette Holdbrook: The work participation rate.

Krissy Clark: The work participation rate.

Jeanette Holdbrook: Or WPR.

Krissy Clark: This is Jeanette Holdbrook with the Public Policy Research Group, Mathematica. She works with state and local welfare offices across the country to study and tried to improve their Temporary Assistance for Needy Families programs. And even though a lot of the rhetoric around welfare reform is about the power of employment to lift people out of poverty, Jeanette says most of the law isn’t actually about employment. One of the only real metrics that states are actually held accountable for around their use of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families dollars is this work participation rate, this little mouthful of a term that sounds so wonky and bureaucratic. And as anyone who’s ever had a performance review with their job knows what’s measured, is ultimately what matters. So what is the work participation rate? What it is, is a measure of how many people who are receiving cash welfare and are required to do some sort of work activity, are actually doing enough hours of that work activity to meet federal guidelines and can prove it.

Jeanette Holdbrook: The really important thing to keep in mind is that this doesn’t tell you anything about the effectiveness of TANF programs. It doesn’t tell you how many people got jobs, it doesn’t tell you how many people no longer need to receive TANF benefits. All it tells you is of the families who can be participating in work activities, how many are participating in work activities.

Krissy Clark: Not how many families are participating in actual paying jobs or paying jobs that get them over the poverty line, just how many are doing some kind of federally approved work activity. So if you do have an actual paying job when you’re on welfare that counts, but if not, the federal government still wants to make sure you’re doing the work related and job readiness activities that your case manager has assigned you to do to meet your work requirement. So take Darnetta, when she missed some hours of that unpaid work experience, she was assigned to do filing paperwork at the community center, or some hours she was supposed to dedicate to job search each week, all the stuff she found hard to juggle while she was trying to get back custody of her son, that could have dragged down the state’s work participation rate. And there are 1000s of Darnetta’s each year, who for one reason or another, also don’t do the amount of work activities they’re supposed to do. If a state doesn’t meet the target work participation rate, there can be serious consequences. The federal government can actually cut the amount of funding states receive from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Block Grant. I’m going to take a minute to say for all the policy wonks out there, that yes, there are ways states can meet this rate more easily. If they can show they’ve reduced the number of people getting welfare by a certain amount each year, which can lead to its own perverse incentives. But Jeanette and many other welfare experts say the bottom line is the mere presence of the word participation rate looms large states still have to measure it and report it each year. The people who administer state welfare programs take it very seriously.

Jeanette Holdbrook: This sounds dramatic, but they still kind of live in fear of these potential penalties from the federal government. And so this drives in many places. This drives this focus on compliance and on documenting what TANF recipients spend their time doing. So, this is why case managers are chasing down pay stubs. This is why you know, case managers are making people fill out logs of every job application that they’ve submitted in the past two weeks, so that they can document this person is participating in work activities. So that my program can make WPR this this single measure that is not an outcomes measure. Drives so much of service delivery, and causes programs to be these kinds of compliance paperwork, chasing machines, just compliance monitoring machines.

Krissy Clark: This is also why case managers sometimes ask a person to provide documentation to explain why they didn’t participate in work activities, like because they had to be in court or their child had just died, or they’d been beat up by their partner. And this is why sometimes people get penalized for missing their work activities and get their cash assistance reduced, you can draw a line from all that back to this drive states have toward this one goal. At one welfare program, Jeanette was consulting for she did a survey of how staff were spending their time during their work day.

Jeanette Holdbrook: And I mean, we found that they spent more than 60% of their time doing paperwork, and data entry. And for people who get into human services, get into programs to help people can be a little soul crushing to then spend so much of your time chasing down documentation so that you can say this person participated for this many hours in this activity.

Krissy Clark: You can imagine a different system. Work requirements are based on the assumption that people on welfare will only work if they’re forced to. But what if rather than requiring people to do work activities and monitoring whether they’re doing them? What if you just gave them money, and then help them find jobs with family sustaining wages, or quality job training? Poof, this compliance machine would go away. But for now, we have it. And there’s a whole private industry that’s been built around operating this compliance machine for states.

Jeanette Holdbrook: I mean, I’ve seen programs where supervisors are every week spending time, I mean, hours, looking at work participation, who doesn’t have documentation that they need. And then you know, chastising case managers, because they haven’t gotten this documentation. So this really drives so much of how staff operate, because it’s always what they’re talking about. Let’s look at who has worked activities, let’s look at who doesn’t have work activities. And so you have no time left to actually have conversations with people or help people build skills or help get them connected to, you know, mental health supports housing counseling, if they have experienced trauma. So getting people into a place where they are ready to get a job and can you know, get their family in a better position?

Krissy Clark: And about those work activities that the work participation rate is measuring? Are they actually getting families into a better position? Well, it’s hard to track that many states barely try. But there have been some rigorous studies that do. And Jeanette says when you gather all their findings, looking at the effects of all these work activities, and just the overall focus on documentation and compliance and sanctions, that exists in most welfare to work programs.

Jeanette Holdbrook: There just wasn’t a lot to show. Over the past 20 years, there’s been this focus on work first and compliance in TANF programs. And broadly, we haven’t seen a lot from that. That hasn’t been the approach that has gotten people into family sustaining wage jobs.

Krissy Clark: Darnetta Harris, the welfare recipient in Milwaukee who had fled domestic violence, she didn’t know about any of these studies. But she did know in her bones that the Welfare to Work System she was in wasn’t working for her. And one day, she tried to send that message to the powers that be, she took all her frustrations about getting sanctioned while she was trying to gain back custody of her son about the futile feeling work experience, she was told to do and turned it all into egg rolls.

Darnetta Harris: Corn beef egg rolls.

Krissy Clark: Corn beef egg rolls?

Darnetta Harris: Yes, when it became popular because that wasn’t a popular thing.

Krissy Clark: One day Darnetta had a meeting with her welfare case manager. And before she went, she was thinking about how blown off she felt by the welfare office when she explained the bind she was in with her custody battle over her child. And all the court hearings she had to make. She was thinking about how unseriously the welfare office seemed to be taking her resume or her skills or her career goals of being an addiction counselor or opening her own restaurant. And she had an idea about a way to send a message directly to her caseworker.

Darnetta Harris: Let me tell you what I did if I can. I cooked for her so she can know what I’m talking about my skills.

Krissy Clark: For your caseworker. Wow.

Darnetta Harris: Just to let her know that I know what I’m talking about. So I had an appointment with her. So before I came, I made the egg rolls. Rolled them up and had my little dipping sauce for her that that I made from scratch. And she was like, What is this? I had a little, little Chinese box full of everything. What is this? This is your lunch for today. I hope you hadn’t ate already or you can add to what you ate. This is something that I made and I wanted you to taste. And she tasted it and she was like, Can I order a whole pan of these? I said can my check not be sanctioned? She was like, Ah, is that what you’re doing? I said, No. I just wanted to show you that I am skillful. I am skillful. That’s it.

Krissy Clark: And did that help you get onto a path through W2 that was helping you with that?

Darnetta Harris: Hell no.

Krissy Clark: Oh, no.

Darnetta Harris: No. I’m sorry, you can edit that part. But nah, no, it didn’t. I just did. I just wanted to let her know she was like you good and did she order that pan, she ordered a pan of them so and she I gave her the varieties that I can make. And she ended up ordering to pay and I hit her pockets. I was like that’s $65 mam.

Krissy Clark: Did she pay?

Darnetta Harris: She paid and they ate it.

Krissy Clark: Ultimately, Darnetta did get a job about two years into her time on W2, a part time job at a restaurant. It didn’t pay much. She made so little $8 an hour that she still qualified for welfare and still had to do other work activities to earn her check. The other thing worth pointing out about this job. She says she found it herself not through any of the job leads that she’d gotten from the private company paid to run the welfare office. She was going to just a job posting she saw one day on the bus. Since then, over the last 10 years, Darnetta has had lots of other jobs. She hasn’t managed to become an addiction counselor or open her own restaurant like she dreamed of yet. For a while she was a cook in a hospital, then a case manager at a nonprofit in Milwaukee that helps people train for jobs. But she points out that program did not involve any work requirements, just work opportunities. And she liked it that way. Rather than being mostly a rule enforcer. She says she could focus on helping her clients and she got a lot of satisfaction assisting people that reminded her of her.

Darnetta Harris: One person graduated to six week culinary program. She graduated number one in her class she she won the chili contest, but I got her a apron with her name on it. And I put a quote at the bottom of it because you saw this you achieve it. I said, have you came up with the restaurant name yet because you said you wanted to be an owner. It’s about a push or some some of us just need to know push. That’s what I was just saying. All I needed was a little push show me to show me get put me in the right direction. Let me point you in the right direction you go from now.

Krissy Clark: But the last we checked in on Darnetta. She’d recently lost her job. She’s looking for a new one, waiting to hear back on some interviews. Meanwhile, she’s taking a class trying to complete her associate’s degree at 46 years old. Money’s running thin. She’s getting food stamps. She’s hoping unemployment insurance will kick in soon. And to make ends meet, she’s selling meals she cooks out of her kitchen. On a recent weekend, she sold out on two dishes and made almost $300 on the menu, beef short ribs and cat fish spaghetti. Next week, if there’s not much good evidence that these welfare work requirement programs help people get out of poverty. And there’s lots of evidence that can be really frustrating. Why do we have them? That’s a story that goes way, way back. And culminates in the 1960s in a small city in New York State with a fraught history.

John Mitchell: We challenge the right of freeloaders to make more on relief than when working. We challenge the right of people to quit jobs at will and go on relief like spoiled children.

Krissy Clark: That’s next week on the uncertain hour.

OUTRO

The future of this podcast starts with you.

This season of “The Uncertain Hour” tells the unheard stories of real people affected by the welfare-to-work industrial complex.

Stories like these are seldom in the limelight. It takes extensive time and resources to do this type of investigative journalism … to help you understand the complexity of our economy and to hold the powerful to account.

We need your support to keep doing impactful reporting like this.

Become a Marketplace Investor today and stand up for vital, independent journalism.